These inset boxes show close-ups of four of the nine objects identified as part of the astronomical platypus sample. All told, these nine objects have a mishmash of properties that don't place them neatly into any one category, but rather they appear as hybrids of galaxies, quasars, and AGNs, where no one class of object matches all of the observed properties.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Steve Finkelstein (UT Austin); Image Processing: Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

Key Takeaways

These inset boxes show close-ups of four of the nine objects identified as part of the astronomical platypus sample. All told, these nine objects have a mishmash of properties that don't place them neatly into any one category, but rather they appear as hybrids of galaxies, quasars, and AGNs, where no one class of object matches all of the observed properties.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Steve Finkelstein (UT Austin); Image Processing: Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

Key Takeaways

- In the animal kingdom, the platypus is one of the most bizarre specimens ever found: an egg-laying mammal with a duck’s bill, beaver’s tail, a shark-like electrolocation sense, and venomous spurs on its hind feet.

- It’s so unusual that it was regarded as a hoax by many, but it’s very real. Any one of these features, on its own, wouldn’t be cause for alarm, but put them all together in a single animal, and it sure does defy expectations.

- Using JWST, astronomers have uncovered nine objects that, similarly, have a collection of properties that, all together, wholly defy our expectations and that lack a cohesive explanation for them. Here’s what the cosmic version of the platypus is all about.

In the animal kingdom, one of the most bizarre discoveries of all-time was the platypus. When reports of the platypus reached the western hemisphere, most leading naturalists at the time assumed it was a hoax, including the first European scientists to examine a specimen in 1799. It was an animal that laid eggs, yet it was a mammal. It had the bill of a duck, but the tail of a beaver. It had (at least, the males do) venomous spurs on their hind legs, but also the ability to locate other creatures in the water through a specialized sense known as electroreception, common in sharks but very rare among mammals. And yet, the platypus exists with all of these properties, even if it would take decades (or more than a century) before we understood how such a creature could come to exist.

Astronomers have just encountered a very similar situation by looking at a large suite of data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). We’ve seen all sorts of objects that we understand fairly well: stars, stellar remnants, galaxies, active galactic nuclei, quasars, and so on. Within all of these categories, there are enormous varieties of properties that individual objects might possess, but there are some general attributes that are common to all of them. So what do you do when, after sifting through the data, you find a significant collection of objects that:

- are point (or, more accurately, point-like) sources,

- located at great cosmic redshifts,

- that have narrow (rather than broad) emission lines,

- and that don’t fall neatly into any of the known categories of astronomical objects.

Could this be the astronomical version of the duck-billed platypus? And if so, what does it mean? Let’s take a deep look at what we’ve just found.

This image of deep space was acquired with JWST’s NIRCam instrument by the CEERS collaboration. Representing just ~2% of their entire field-of-coverage, nearby, intermediate, and distant galaxies all appear together, with just a total of 1 hour of exposure time. The bluest galaxies generally represent the closest ones, while the redder ones are either more distant or inherently dusty. Note the rarity of point-like objects, and the commonness of extended objects: the known and identified galaxies.

This image of deep space was acquired with JWST’s NIRCam instrument by the CEERS collaboration. Representing just ~2% of their entire field-of-coverage, nearby, intermediate, and distant galaxies all appear together, with just a total of 1 hour of exposure time. The bluest galaxies generally represent the closest ones, while the redder ones are either more distant or inherently dusty. Note the rarity of point-like objects, and the commonness of extended objects: the known and identified galaxies.Credit: NASA/STScI/CEERS/TACC/S. Finkelstein/M. Bagley/R. Larson/Z. Levay; modifications by E. Siegel

In astronomy, we’ve seen objects that appear point-like before. The most common point-like objects are stars, including practically every star that’s more distant than our Sun is. Stars are large in terms of size — our own Sun is more than 100 times the diameter (and a million times the volume) of Earth — but those sizes are very small compared to the actual distances to the stars. Even a large object, one millions of kilometers across, is going to appear point-like if it’s far enough away. At its current distance of 150,000,000 kilometers away, the Sun takes up about half-a-degree in angular size. If it were instead located at the distance of Proxima Centauri, the nearest star to us, it would take up less than 7 milli-arc-seconds in the sky, or less than 1 pixel to even JWST’s eyes.

But the stars we can see and individually resolve are all relatively nearby: located within the Milky Way, Local Group, or other galaxies that are found in our cosmic backyard. Any individual star located at distances more than a couple of hundred million light-years away, even in the JWST era, could only be spotted either as part of a star cluster or larger aggregation of stars, or else would have to be significantly gravitationally lensed to be seen individually. These nine “platypus” like objects, however, are all located at great redshifts: redshifts between z = 3.6 and z = 5.4, completely ruling out the possibility of these objects being stars.

These nine panels show the image stamps and spectra as a function of wavelength and amplitude of the nine identified platypus objects. The images in the grey boxes are just 1.6 arc-seconds on a side, and the red circles are 0.64 arc-seconds in radius. The leftmost two boxes represent Hubble data, while all the remaining boxes represent JWST data. Oxygen and hydrogen emission lines are marked.

Credit: H. Yan, B. Sun, and R. Shive, arXiv:2509.12177, 2025

These nine panels show the image stamps and spectra as a function of wavelength and amplitude of the nine identified platypus objects. The images in the grey boxes are just 1.6 arc-seconds on a side, and the red circles are 0.64 arc-seconds in radius. The leftmost two boxes represent Hubble data, while all the remaining boxes represent JWST data. Oxygen and hydrogen emission lines are marked.

Credit: H. Yan, B. Sun, and R. Shive, arXiv:2509.12177, 2025

Instead of coming from nearby, the light from these objects must be coming, based on their identified redshifts, from long ago: from when the Universe was just 1.2 to 1.8 billion years old, as opposed to its modern age of 13.8 billion years. This is far past the limits of where individual stars can be resolved, but is located at the great cosmic distances where three classes of known objects do readily exist:

- galaxies,

- active galactic nuclei (also known as AGNs),

- and quasars.

Galaxies tend to be extended objects, even at these great redshifts, so that seems an unlikely candidate for these point-like objects. However, because we’re dealing with objects that don’t fit neatly into any known individual category, we’ll keep them in mind and return to that possibility later.

However, both AGNs and quasars can appear point-like, as they’re thought to arise from actively feeding supermassive black holes. Quasars, in particular, are often point-like, as they are very bright, unobscured supermassive black holes, whose jets and accretion disks shine from the intense heat and energy injected into them. However, because that material is so close to the black hole, quasars normally exhibit what we call “broad-line” emission, where the large internal velocities of the material orbiting so close to the black hole gets imprinted onto the emission line signature.

This graphic illustrates the pronounced narrow peak of the spectra that caught researchers’ attention in a small sample of galaxies, represented here by the galaxy CEERS 4233-42232. It is the combination of a narrower-than-expected spectra, along with a tiny, point-like appearance, that makes these galaxies stand out. Typically, distant point-like light sources are quasars, but quasar spectra have a much broader shape.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph Olmsted (STScI)

This graphic illustrates the pronounced narrow peak of the spectra that caught researchers’ attention in a small sample of galaxies, represented here by the galaxy CEERS 4233-42232. It is the combination of a narrower-than-expected spectra, along with a tiny, point-like appearance, that makes these galaxies stand out. Typically, distant point-like light sources are quasars, but quasar spectra have a much broader shape.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph Olmsted (STScI)

Unfortunately for the quasar hypothesis, the signatures of these nine “platypus” objects don’t have broad-line emissions, but instead display narrow-line emissions. A comparison of a typical quasar spectrum with its characteristic broad lines is shown above, alongside the spectrum of a typical member of this platypus-like sample. As you can clearly see, the lines in these cosmic platypi are quite narrow: much narrower than they appear within quasars. In addition, although it isn’t accurately represented in the magnitude of the illustrated spectrum, quasars are normally extremely bright: among the brightest individual sources in the Universe. These platypus-like objects, on the other hand, are much fainter than even the most modest quasars.

However, there is a candidate for objects that appear at great redshifts (and hence, great cosmic distances) that do exhibit narrow emission lines: AGNs, or active galactic nuclei. The class of narrow-line AGNs, sometimes known as type 2 AGNs, certainly does exhibit narrow emission lines, and they do appear at high redshifts, just like these platypus objects do. We can look at the individual spectra of the nine identified platypus objects, and see, as shown below, that they do indeed seem to be consistent with the type 2 AGN explanation.

The nine platypus objects are shown here at the particular wavelength that a strong emission line signature appears. The width of these lines contains information about either the temperature or the motions of the gas that’s emitting them, pointing to narrow emission lines that are simply not characteristics of quasars, but that do sometimes appear within type 2 active galactic nuclei (AGNs).

Credit: H. Yan, B. Sun, and R. Shive, arXiv:2509.12177, 2025

The nine platypus objects are shown here at the particular wavelength that a strong emission line signature appears. The width of these lines contains information about either the temperature or the motions of the gas that’s emitting them, pointing to narrow emission lines that are simply not characteristics of quasars, but that do sometimes appear within type 2 active galactic nuclei (AGNs).

Credit: H. Yan, B. Sun, and R. Shive, arXiv:2509.12177, 2025

But then we run into a different problem: all of the type 2 AGNs that we know of are not point-like, but instead are extended objects. Moreover, most AGNs have, especially with deep imaging (like the kind of imaging that JWST performed to even detect these rare objects), resolvable host galaxies: galaxies that can be identified alongside the signatures of the active galactic nucleus present within them. However, all nine of these platypus objects are hostless. This means that if these objects truly are AGNs, they represent an all-new class of AGN: AGNs that are low-luminosity, hostless, and point-like.

What other options are left? These newly discovered objects don’t appear to match the properties, across the board, of any known set of objects that have been spotted previously.

One interesting property to note, and perhaps this is a great clue, is that these objects aren’t exactly analogous to what we call point sources, but instead are what astronomers call point-like. Ideally, in any telescope, including JWST, we know exactly how a detector will see a perfect point source. It won’t appear as though it takes up just a single pixel on the detector, despite what you might think. Instead, it makes a signal known as a point-spread function, which depends on the specific optics of the telescope in question, as well as the design, efficiency, and throughput of the detector.

The point spread function for the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), as predicted back in a 2007 document. The four factors of a hexagonal (not circular) primary mirror, composed out of a set of 18 tiled hexagons, each with ~4 mm gaps between them, and with three support struts to hold the secondary mirror in place, all work to create the inevitable series of spikes that appear around bright point sources imaged with JWST. This pattern has been affectionately called the “nightmare snowflake” by many of JWST’s instrument scientists.

Credit: R. B. Makidon, S. Casertano, C. Cox & R. van der Marel, STScI/NASA/AURA

The point spread function for the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), as predicted back in a 2007 document. The four factors of a hexagonal (not circular) primary mirror, composed out of a set of 18 tiled hexagons, each with ~4 mm gaps between them, and with three support struts to hold the secondary mirror in place, all work to create the inevitable series of spikes that appear around bright point sources imaged with JWST. This pattern has been affectionately called the “nightmare snowflake” by many of JWST’s instrument scientists.

Credit: R. B. Makidon, S. Casertano, C. Cox & R. van der Marel, STScI/NASA/AURA

For JWST, that point-spread function has been well-studied and well-quantified. Originally, astronomers were terrified of what that shape would be, and dubbed it “the nightmare snowflake.” However, as we calibrated and became more and more familiar with the images that JWST was producing, that snowflake-shape began to acquire a beauty all unto itself, and distant point sources that truly behaved as point sources became well-understood, even when viewed by JWST. The key was understanding how energy, or brightness, would “bleed” into the surrounding pixels from an individual point source, and then by plotting out that energy distribution as a function of angular separation.

The reason these objects are called “point-like” sources instead of point sources is because they don’t match up exactly with the idealized point-spread function of a true point source. In detail, they differ in three key ways:

- There’s a little more energy found farther away from the center rather than located in the exact center, potentially indicating an extra “spread” as compared with a true point object.

- At distances from between 2-5 pixels from the center, the amount of energy found within these platypus objects is maximally greater than the expectation for a true point source.

- And that, overall, the point-spread function differs by around 10-20% from a true point source, with the largest difference for any one object coming in at ~35%.

They are very point-like, but there are a few things about them that are different from a perfect point source.

This series of graphs shows, for eight of the platypus objects currently identified, the distribution of light and energy as a function of number of pixels away from the center of the identified source. The dotted lines show what a true point source’s appearance would be; the actual data (in grey) and the best fit line (black) to that data are shown for comparison. On average, they differ from a true point source by 10-20%, making them point-like but not identical to true point sources.

Credit: H. Yan, B. Sun, and R. Shive, arXiv:2509.12177, 2025

This series of graphs shows, for eight of the platypus objects currently identified, the distribution of light and energy as a function of number of pixels away from the center of the identified source. The dotted lines show what a true point source’s appearance would be; the actual data (in grey) and the best fit line (black) to that data are shown for comparison. On average, they differ from a true point source by 10-20%, making them point-like but not identical to true point sources.

Credit: H. Yan, B. Sun, and R. Shive, arXiv:2509.12177, 2025

So what does all of that imply, or at the very least, suggest? One possibility that’s extremely compelling arises if we ask, “what if it’s none of the point-like candidates we’ve considered thus far?” In other words, what if it’s not a star, not a quasar, and not an AGN? Is there anything else that’s worth considering?

Earlier, we brought up the possibility that these platypus objects are actually distant galaxies, and we ruled it out because galaxies tend to be extended objects. These objects, however, appear point-like, and that seems to contradict the very idea that these might be galaxies.

But what if they really are galaxies? Remember: the galaxies we’re most familiar with are the ones we see at late times: after billions of years have passed and many generations of stars had formed within them previously. Still, we know there must have been a time when the modern, grown-up galaxies we see today formed stars for the very first time, and we know of exactly zero examples — from our Local Group to the greatest distances that our space telescopes have ever seen — of galaxies that are made of this pristine material, or are forming stars for the first time. These platypus objects can’t be those pristine galaxies (because the gas within them is enriched with heavy elements, pointing to previous generations of stars within them), but they might be the very next stage in their evolution.

This image shows how a galaxy’s spectral energy is distributed: from ultraviolet wavelengths (starting at the lower-left and proceeding clockwise) through the visible light spectrum under blue, green, yellow, orange, and red filters, all the way to infrared wavelengths (at the lower-right). Brighter colors indicate greater energy densities. Whether a galaxy is young, old, or actively forming stars now heavily impacts what its spectral energy distribution, and hence what its appearance and brightness is like at different wavelengths, will be.

This image shows how a galaxy’s spectral energy is distributed: from ultraviolet wavelengths (starting at the lower-left and proceeding clockwise) through the visible light spectrum under blue, green, yellow, orange, and red filters, all the way to infrared wavelengths (at the lower-right). Brighter colors indicate greater energy densities. Whether a galaxy is young, old, or actively forming stars now heavily impacts what its spectral energy distribution, and hence what its appearance and brightness is like at different wavelengths, will be.Credit: NASA, ESA, Dan Maoz (Tel-Aviv University, Israel, and Columbia University, USA)

One interesting piece of evidence we haven’t looked at yet is the spectral energy distribution of these objects. While that might sound like an intimidating name — spectral energy distribution — it simply means how the energy of an object is distributed as a function of wavelength: ultraviolet light, blue light, green light, yellow light, red light, and infrared light, as granularly as your instrument suite will allow you to get. When we look at the spectral energy distributions of these nine platypus objects, one is consistent with being an AGN, but the other eight are all consistent with the known spectral energy distributions that are common to galaxies.

So could they be galaxies? It isn’t ruled out, but again, if they are galaxies, they’re galaxies that have different properties from the common galaxies we’re familiar with today. In particular, they’d have to be galaxies with:

- very young stellar populations, that only began forming stars 100-200 million years prior to how we’re seeing them,

- that are relatively low in mass, with only about 300 million stars worth of stellar mass (comparable to the stellar mass of the Small Magellanic Cloud),

- that are indeed forming stars, but not at a breakneck pace (forming just under 2 solar masses worth of new stars each year),

- and that have a much lower abundance of heavy elements than the Milky Way does, with oxygen abundances between 16-50% what we see locally.

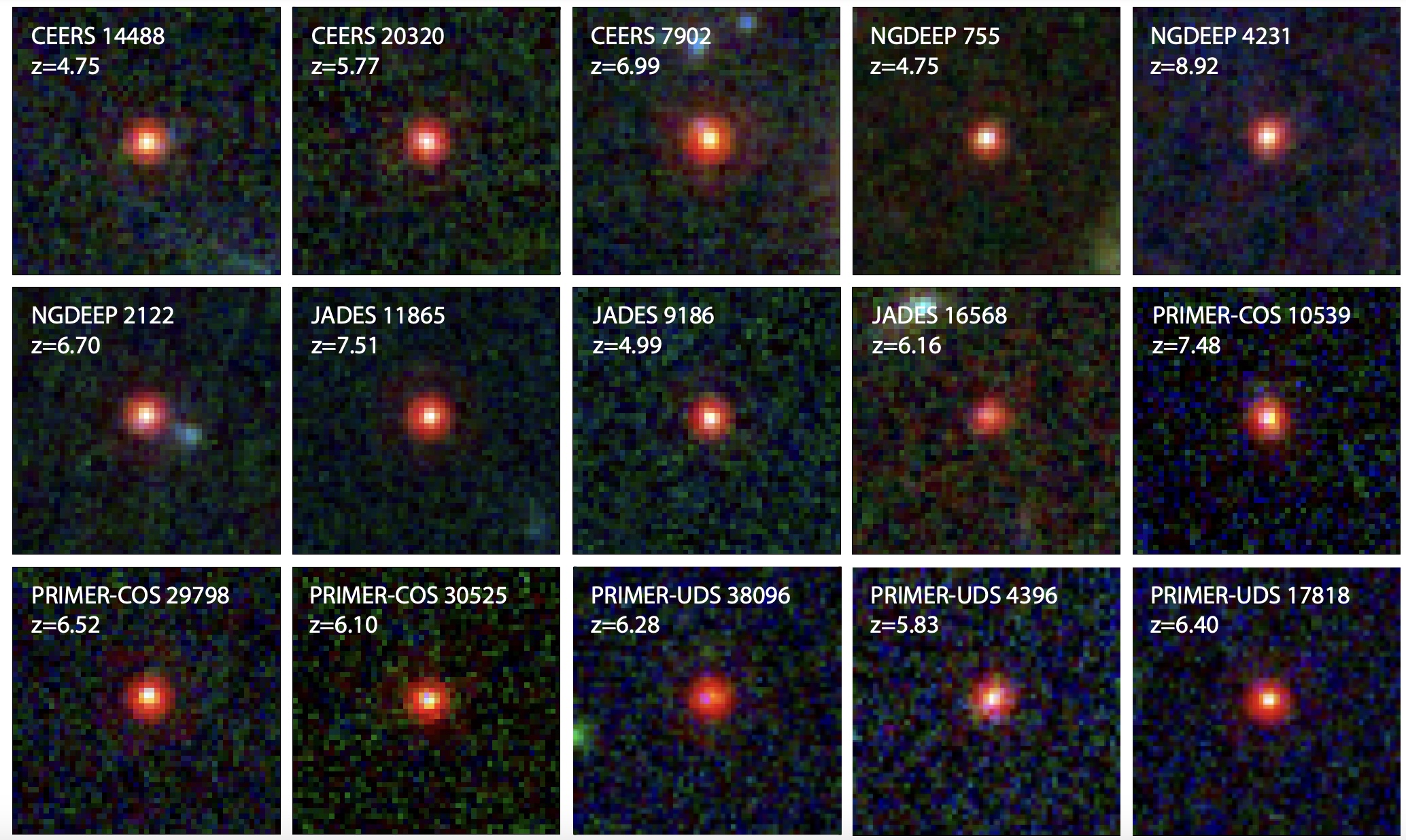

This image shows 15 of the 341 hitherto identified “little red dot” galaxies discovered in the distant Universe by JWST. These galaxies all exhibit similar features, but only exist very early on in cosmic history; there are no known examples of such galaxies close by or at late times. All of them are quite massive, but some are compact while others are extended, and some show evidence for AGN activity while others do not. Like the platypus objects, they don’t have resolved galactic hosts, but unlike them, they don’t match the spectral energy density of galaxies.

This image shows 15 of the 341 hitherto identified “little red dot” galaxies discovered in the distant Universe by JWST. These galaxies all exhibit similar features, but only exist very early on in cosmic history; there are no known examples of such galaxies close by or at late times. All of them are quite massive, but some are compact while others are extended, and some show evidence for AGN activity while others do not. Like the platypus objects, they don’t have resolved galactic hosts, but unlike them, they don’t match the spectral energy density of galaxies.Credit: D. Kocevski et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters accepted/arXiv:2404.03576, 2025

If these platypus objects do turn out to be galaxies, they’d have to represent a wholly new class of galaxies: very young objects that are only beginning to grow, now, after starting their formation process from an extremely compact core. This isn’t out of the question, as one of the main theoretical scenarios involved in forming galaxies for the first time is the evolution of a large clump of matter that underwent monolithic collapse to form the first few generations of stars. However, such a scenario remains unvalidated by the data, and so if these platypus objects represent a new type of galaxy, they would indeed be the first known examples of their kind.

To be certain, the nature of these platypus objects and whether they’re a new type of narrow-line quasar, a new type of low-luminosity, hostless AGN, or a new type of compact, recently formed galaxy (or something else entirely) remains ambiguous. As we often say, a new discovery in science doesn’t often sound like, “eureka!” but rather, “that’s funny,” and these platypus objects, whatever their true nature turns out to be, do indeed look awfully funny when we contrast them with all the known, understood objects that are comparable to them in any way.

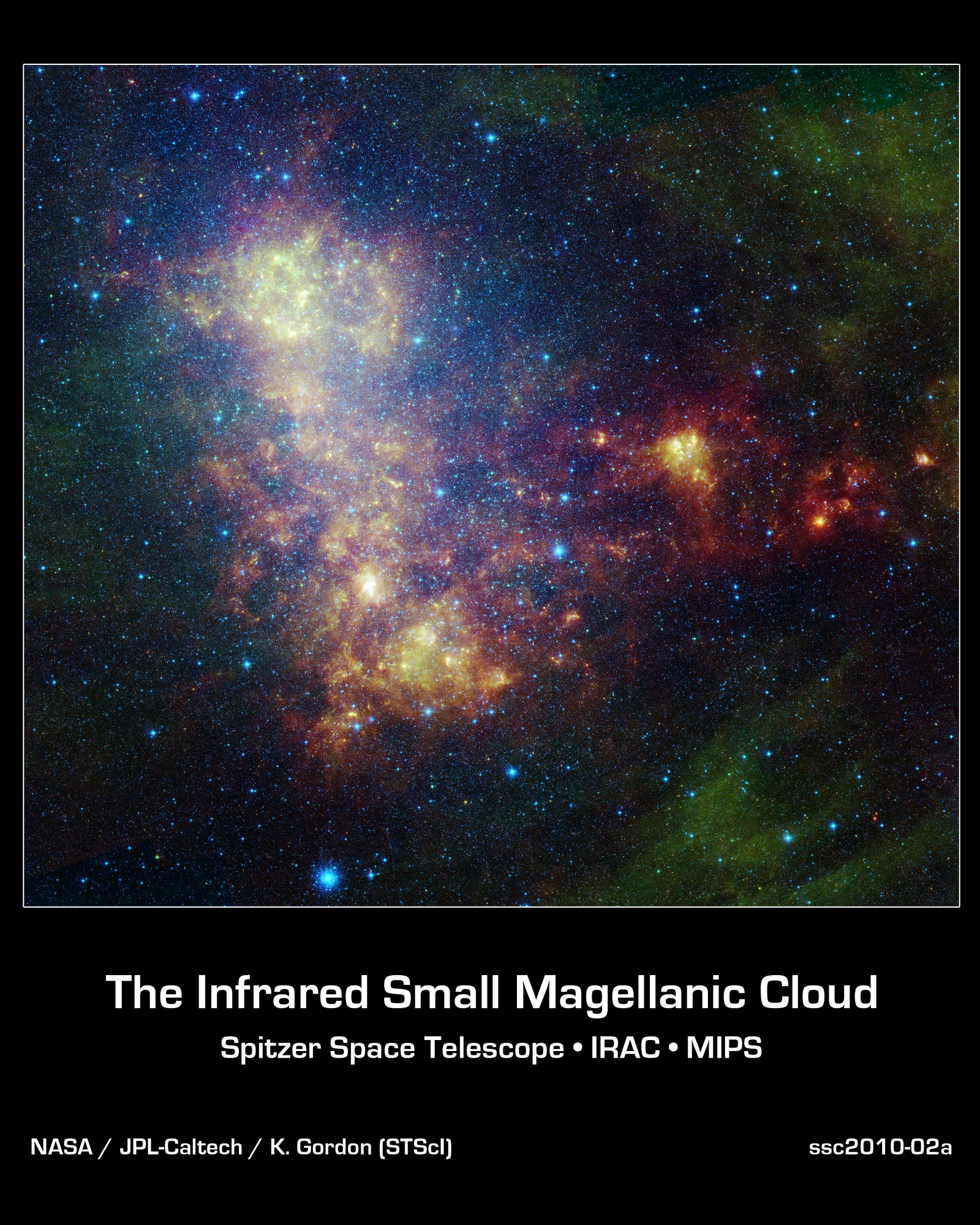

This infrared portrait of the Small Magellanic Cloud, located just 199,000 light-years away, highlights a variety of features, including new stars, cool gas, and quite spectacularly (in green) the presence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: the most complex organic molecules ever found in the natural environment of interstellar space. With 300,000,000 solar masses worth of stars within it, the SMC has a comparable stellar mass to the known platypus objects, but is older, more evolved, and less compact than any of them.

This infrared portrait of the Small Magellanic Cloud, located just 199,000 light-years away, highlights a variety of features, including new stars, cool gas, and quite spectacularly (in green) the presence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: the most complex organic molecules ever found in the natural environment of interstellar space. With 300,000,000 solar masses worth of stars within it, the SMC has a comparable stellar mass to the known platypus objects, but is older, more evolved, and less compact than any of them.Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Deeper imaging and higher-resolution spectroscopy, covering even broader wavelength ranges than we’ve probed these platypus galaxies with so far, could provide key insights into decoding their nature, and in enabling us to understand even more about them than these early studies have revealed.

Perhaps it’s also worth recalling the story of the original platypus: the odd duck-billed, beaver-tailed, egg-laying semi-aquatic mammal with webbed front feet, poisonous rear ankle spikes, and a sense of electroreception. Originally, it seemed like a type of chimera: a mythical creature that’s a hodgepodge of traits that simply don’t belong together. However, subsequent scientific research revealed that they’re a part of a rare but important group of mammals known as monotremes, which include four species of echidna. Additionally, the fossil record supports a large ancient population of venomous mammals; the platypus likely represents one of the few extant survivors. Additionally, fossil records going all the way back to the Cretaceous suggest that the platypus family, Ornithorhynchidae, has a long history going back more than 95 million years. It’s only the fact that the platypus we know is the last surviving example of that family that makes it appear so bizarre and unfamiliar to us today.

Perhaps someday, perhaps even in the very near future, we’ll make sense of these astronomical platypi, and acquire the new data we need to truly determine their natures. At present, we know they’re not a hoax, but their ultimate origins remain mysterious.

Tags Space & Astrophysics In this article Space & Astrophysics Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all. Subscribe