William E. Wallace openly uses what he calls “informed imagination” to explore the relationship between the two masters in his new study.

Olivia McEwan

January 28, 2026

— 4 min read

Olivia McEwan

January 28, 2026

— 4 min read

Titian Vecellio, "Venus and the Lute Player" (c. 1565–70), oil on canvas; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (© The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Titian Vecellio, "Venus and the Lute Player" (c. 1565–70), oil on canvas; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (© The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Pay heed to the word “tale” in the title of William E. Wallace’s book Michelangelo & Titian: A Tale of Rivalry and Genius. Wallace, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis, is a world authority on Michelangelo. Yet unlike his eight prior academic titles on the artist, this one is not grounded in new or existing primary sources, for there is scant evidence linking Michelangelo and Titian. Moreover, Wallace openly uses what he calls “informed imagination” to explore their relationship, at times straying into narrative mode to tell a story of the two artists’ experiences and thoughts.

This liberal use of imagination prevents the book from becoming a core academic text. Yet before art historians shout “stop: balderdash!” it’s worth noting that Wallace raises the very interesting and valid question of what can and cannot be admitted as historical evidence. While art history is founded on empirical primary sources, he rightly highlights the value — and vastly greater volume — of unrecorded oral history. Naturally, knowledge and ideas were perpetuated, percolated, and precipitated through conversations, visitations, viewings, and gossip that we can never fully access. However, like mosaic theory in finance, in which many different forms of information are combined to inform insight, Wallace considers circumstantial evidence and supposition to arrive at his conclusion — that despite only meeting twice in their lives, Michelangelo and Titian were nonetheless entwined in “long time mutual regard and reciprocal creativity.”

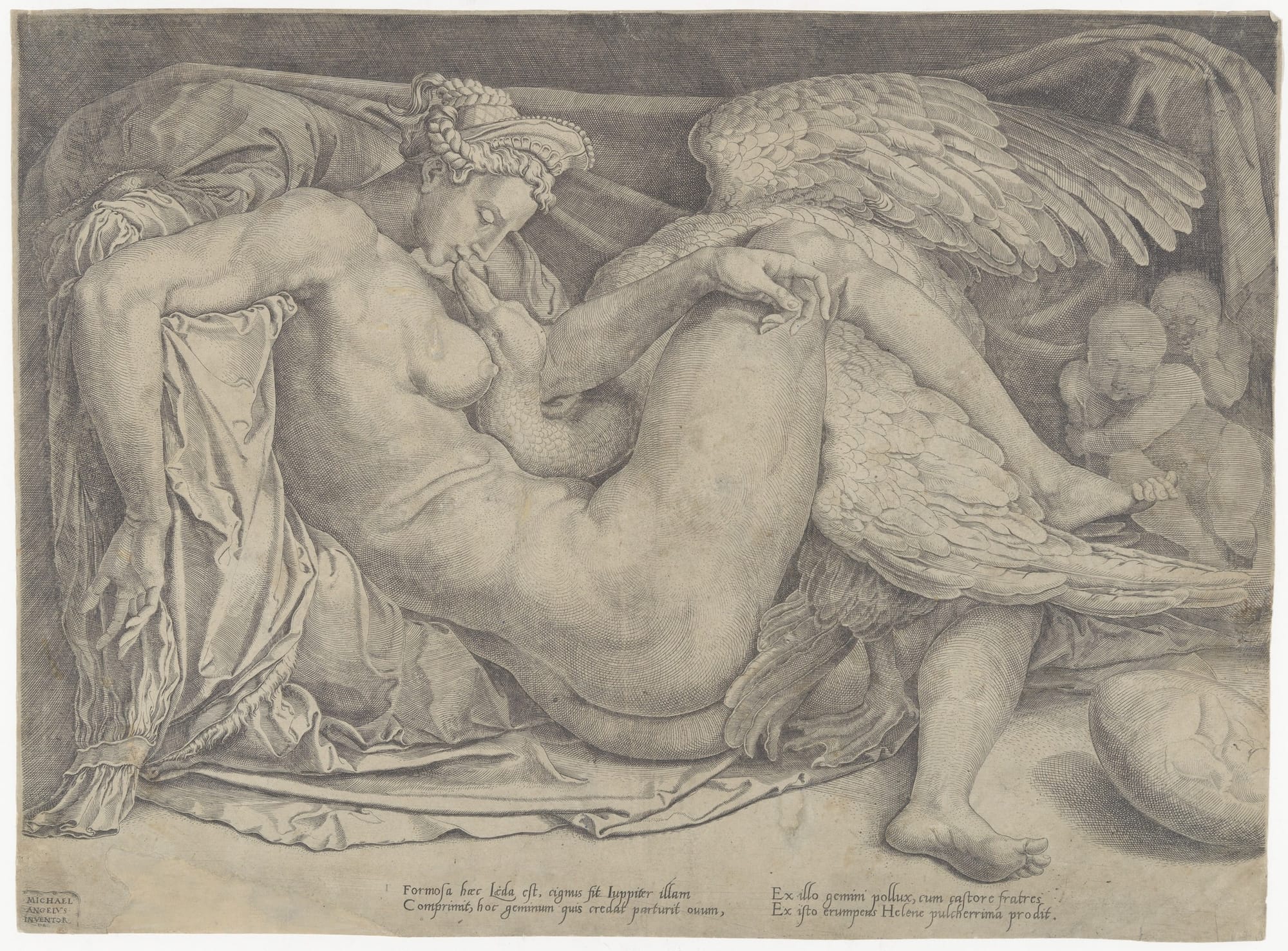

Cornelius Bos after Michelangelo’s "Leda" (late 1530s), engraving; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (© The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Cornelius Bos after Michelangelo’s "Leda" (late 1530s), engraving; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (© The Metropolitan Museum of Art)And there is a heck of a lot of circumstantial evidence and supposition. Wallace details chronologically each artists’ geographical location at various points in time, in relation to concurrent political machinations and movements of key players (artists, patrons, governmental figures, Popes, etc.), for an almost exhaustive account of all potential factors that could inform their behaviors and (somewhat presumptuously) their thoughts and feelings. For example, he posits that Michelangelo began “Leda and the Swan,” created for the Duke Alfonso d’Este in 1529 alongside diplomatic wrangling for his favor, in response to his having seen Titian’s “Bacchus and Ariadne” in the Duke’s collection, citing this as one of the artists’ earliest “encounters.” This one-sentence summary is condensed from around 10 pages of discussion regarding convoluted political circumstance, where Wallace perceives deliberate infusion of eroticism to match Bacchus, and stylistic choices to flatter the Duke’s tastes. Throughout, I was constantly searching for footnotes that would reveal the sources for, and validity of, such assertions. As with all examples in the book, the garden path is indeed long and winding, and the conclusions bald: “Michelangelo never forgot Titian’s leaping Bacchus.” When Wallace adds actual contemporaneous quotes regarding Michelangelo’s supposed memory, he seems to be asking: How could we argue?

Titian Vecellio, "Judith with the Head of Holofernes" (c. 1568/70), oil on canvas; The Detroit Institute of Arts (© Detroit Institute of Arts)

Titian Vecellio, "Judith with the Head of Holofernes" (c. 1568/70), oil on canvas; The Detroit Institute of Arts (© Detroit Institute of Arts)Wallace excessively relies on Vasari’s Lives of the Artists as a primary source for their activities. The famous study is roughly contemporaneous with the artists’ lives, but it’s become notorious for its disproportionate Michelangelo bias, which art historians should season liberally with salt before reading. To his credit, Wallace fully acknowledges this. Yet he regularly singles out the artists as directly influencing one another when, by the same presumption, both would have encountered and absorbed a melting pot of ripe artistic activity. After all, the two met only twice and certainly did not correspond. He argues that for Michelangelo’s “Last Judgement he recalled Titian’s brilliant blue colour,” prompting him to purchase the exorbitantly expensive pigment from Venice. This positions Titian as the spokesperson for a whole city of artists famous for their colore. An interesting observation regarding the nature of copying, absorption, and development inadvertently addresses the core art historical conundrum of proving influence in itself: “As is characteristic of Michelangelo, who drew as much inspiration from his own inventions as of others … [he] generated another [sketch] and another until we arrive at what might be considered an ‘original idea.'” This brings into question the art historical practice of visual comparison without additional contextual and circumstantial background.

Some readers may find parallels with Vasari’s subjective accounts in that Wallace juxtaposes primary sources with imagined scenarios. Whether you are comfortable letting recorded evidence sit alongside unprovable supposition will greatly dictate your experience of the book. However, Wallace has 40 years’ worth of academic knowledge on the subject, and he duly emphasizes “informed imagination.” For readers frustrated by dry art historical studies, he conjures a lively and believable world imbued with emotion absent from typical textbooks. The book can also be considered as a theoretical excursion by an expert on the topic — even if not provable, it prompts a more abstract form of thinking on the subject.

Antonio Maria Zanetti, "Figure" from the façade of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi (c. 1760), engraving (© Houghton Library, Harvard University)

Antonio Maria Zanetti, "Figure" from the façade of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi (c. 1760), engraving (© Houghton Library, Harvard University)On the point of imagination, some passages are wholly narrated as dramatic scenes, such as Vasari chaperoning Michelangelo’s visit to Titian’s studio in Rome in 1546: “On a damp dreary day, Giorgio Vasari stepped over a fresh pile of dung to knock on Michelangelo’s door.” These are written with such gleeful vivacity that Wallace could easily turn his hand to successful historical fiction, should he so wish, for, in his words, “I wish to tell the story.”

Michelangelo & Titian: A Tale of Rivalry and Genius by William E. Wallace (2026) is published by Princeton University Press and is available on February 3 online and in bookstores.