- Asia

- South Asia

Maiwand Banayee, one of the few Afghans to escape the Taliban’s ideological grip, offers a rare account of life forged in war and a long journey out of extremism in an interview with Shweta Sharma

Monday 08 December 2025 03:44 GMTComments

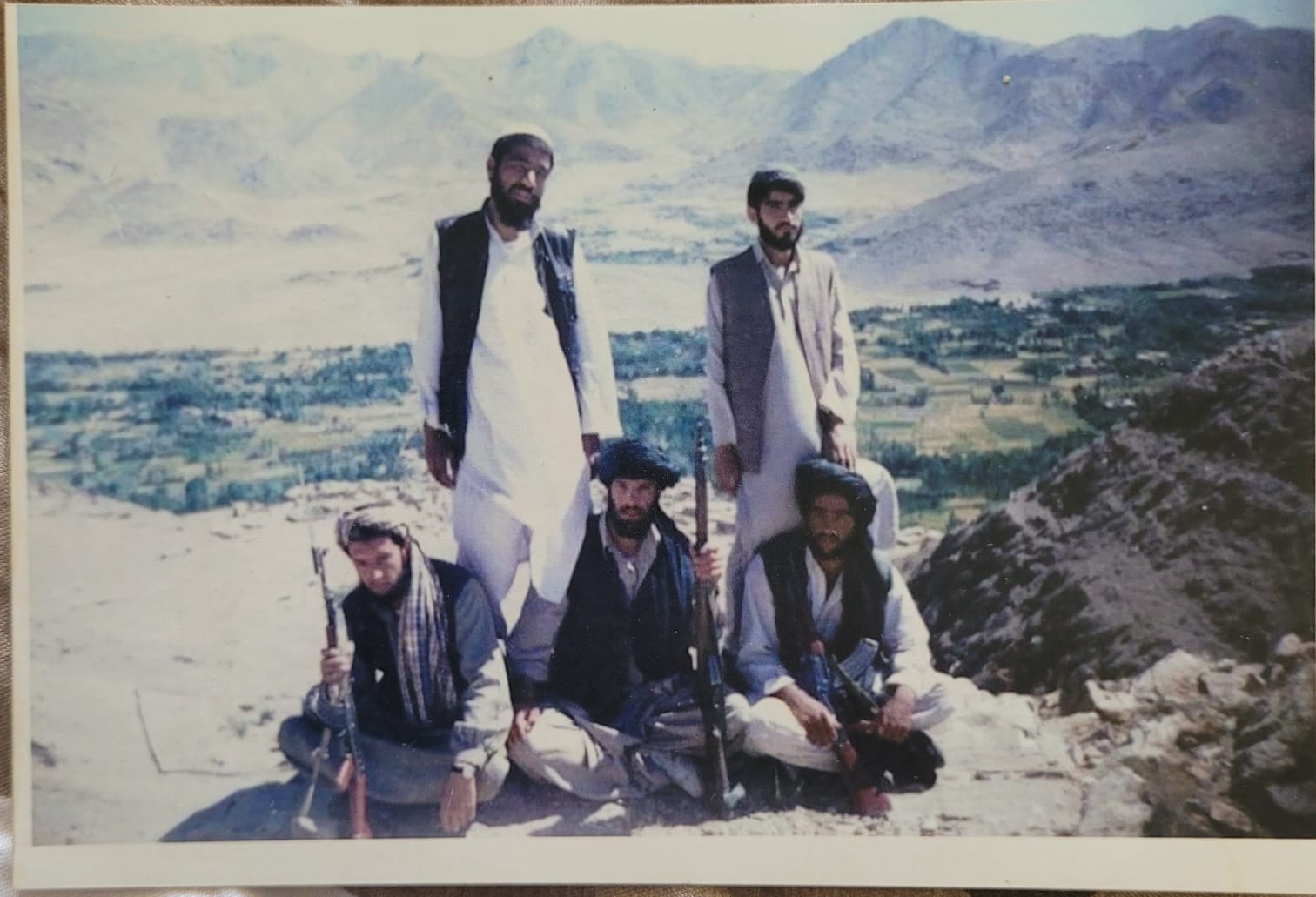

Monday 08 December 2025 03:44 GMTComments open image in galleryMaiwand Banayee, sitting on the far right, with fellow Taliban fighters in Maidan-Shar, Afghanistan (Supplied)

open image in galleryMaiwand Banayee, sitting on the far right, with fellow Taliban fighters in Maidan-Shar, Afghanistan (Supplied)

On The Ground newsletter: Get a weekly dispatch from our international correspondents

Get a weekly dispatch from our international correspondents

Get a weekly international news dispatch

Email*SIGN UP

Email*SIGN UPI would like to be emailed about offers, events and updates from The Independent. Read our Privacy notice

“A for Ahmad, J for jihad, G for gun.”

Thus was Maiwand Banayee introduced to the English alphabet as a young boy in an Islamic seminary, a cluster of mud houses scattered about the swept arid landscape of a refugee camp in northwest Pakistan, where his family had escaped the Afghan civil war.

Three decades on, that world feels impossibly distant from Banayee’s life in the north of England. Banayee, now aged 45, spends his days at an NHS physiotherapy clinic, guiding patients as a diabetes-remission coach. He speaks fluent English, is close to completing an MSc in Physiotherapy Leadership, and is well-regarded by patients for his gentle manner and calm reassurance.

Few who meet him in the comforting corridors of the clinic can imagine the world he escaped or fathom that the same hands now easing chronic pain once held an AK-47, which made that teenage boy feel as if “the world was under my feet”.

In another life arc, Banayee could have been living as a Taliban fighter somewhere in the pitiless mountains of Afghanistan or, perhaps more likely, he could have died a suicide bomber, chasing martyrdom as his greatest goal.

That he ended up instead a healer of the sick half way around the world is a remarkable story of courage and perseverance.

Born into a Pashtun family in a poor neighbourhood of western Kabul, Banayee’s earliest memories were shaped by the Soviet occupation – wrecked buildings, the constant thud of rockets, the drifting black smoke of unrelenting bombardment.

“By the time I became a teenager,” he recalls, “Kabul was a ghost of a city. It was in ruins. Everywhere were lives lost, broken, marginalised.”

Then came the civil war of the 1990s.

A loose coalition of militant groups – the Mujahideen, supported and supplied by the US and fellow Western powers – had chased away the Soviet military in 1989 after a decade of occupation and repression, only to turn their guns on each other in a brutal struggle for power and the spoils of war.

The civil war consumed entire neighbourhoods – as it did generations – and from its cinders rose the Taliban.

The Taliban – literally, the pupils – started as a ragtag militia of a few dozen seminary students, led by a mysterious cleric named Mullah Mohammad Omar, who rebelled against the suffocating repression of Mujahideen factions and sundry warlords and restored a semblance of order, earning public support.

They emerged out of southern Afghanistan and, in just a few short years, came to rule most of the country under a uniquely South Asian interpretation of Islamic law.

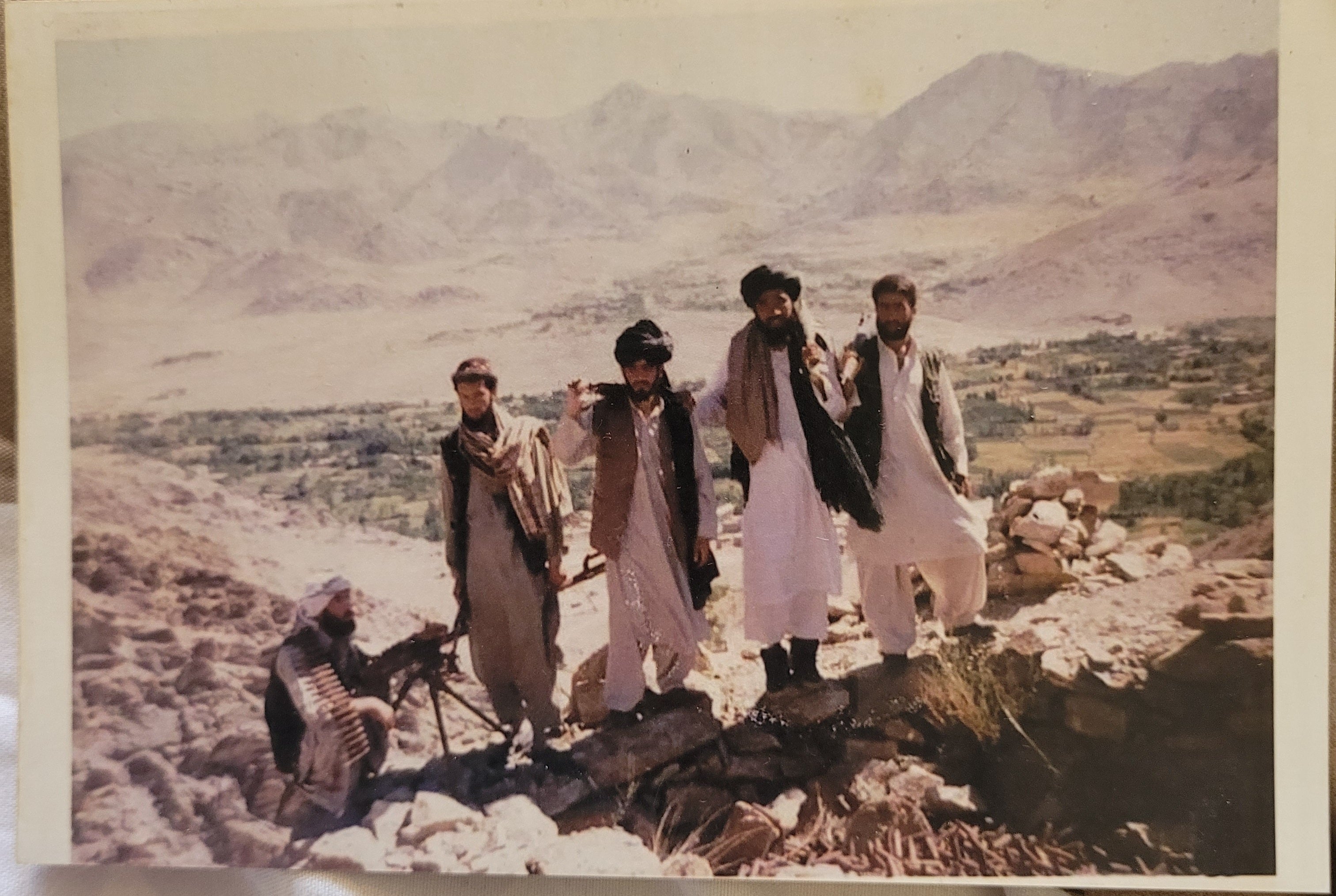

open image in galleryMaiwand Banayee, extreme right, with fellow Taliban fighters at Kharote village (Supplied)

open image in galleryMaiwand Banayee, extreme right, with fellow Taliban fighters at Kharote village (Supplied)Banayee is a rare insider who can speak of life in the Taliban’s recruitment pipeline, a boy once groomed to become a suicide fighter who somehow broke free.

His story is a window onto the world of seminaries and refugee camps that have shaped generations of Afghan boys with a blend of deprivation, propaganda and religious absolutism.

And he fears history is repeating itself. “My story begins with ‘I’, but it’s not a story about me,” he says, sitting in the comfort of his living room in England.

“There are hundreds of thousands of Maiwands like me being groomed right now,” Banayee explains.

“As of today, around seven million children are attending madrasas in Afghanistan. Many could become potential Islamists, jihadists. They may be hungry, traumatised, sexually repressed, stressed, and completely vulnerable.”

Banayee’s own early life was shaped by his name. His father, he recalls, had asked him to live up to his name of Maiwand, honouring the 1880 battle near Kandahar in which Afghan forces inflicted a crushing defeat on invading British and Indian troops.

“But there was a big gap between my father’s expectations and who I was,” he says. “I was sensitive, bookish, and constantly bullied, beaten and spat at in the streets. Kids used to call me afghani gol, meaning stupid. It always pained me. I wanted to claim my real name.”

In a small act of defiance, Banayee tried carving his name on an electricity pole. When his school principal stopped him, he was humiliated. “My trouser string snapped, it fell to the ground, and he pinned me down until the shopkeeper came to free me.” Utter humiliation in a culture obsessed with masculinity. Scared his father would call him a coward, he returned the next day with a rock, ready to fight.

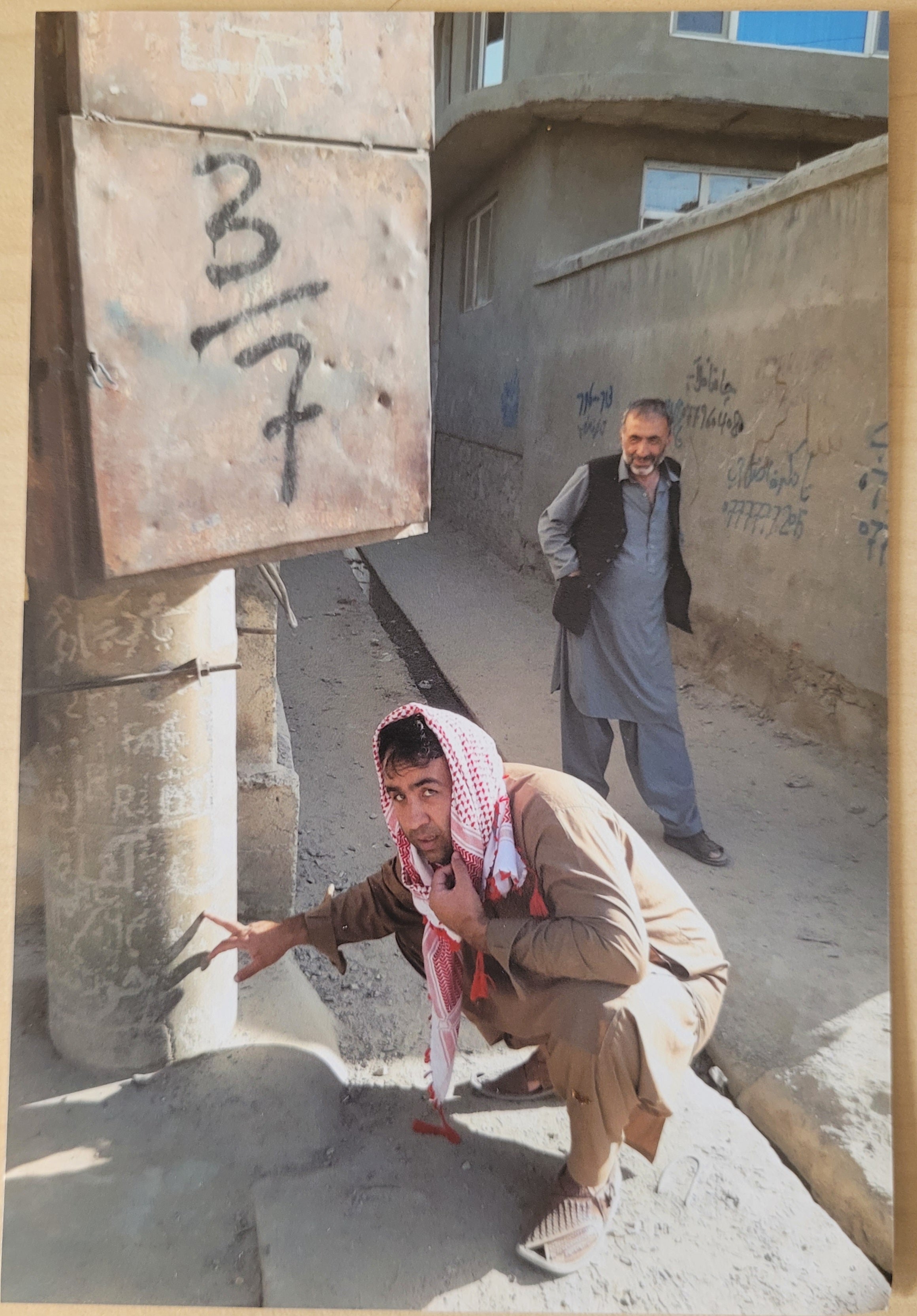

open image in galleryMaiwand Banayee shows the electricity pole where he had tried to carve his name in Kabul (Supplied)

open image in galleryMaiwand Banayee shows the electricity pole where he had tried to carve his name in Kabul (Supplied)Destiny had other plans. Chaos swept his village as news spread that the communist regime propped up by the Soviets had collapsed and the Mujahideen had taken over, plunging the country into civil war.

“Streets emptied, bullets started flying, rockets were roaring,” he recalls. “In that commotion, I ran home.”

That was when his family decided to flee Kabul. Banayee’s father stayed behind with his disabled sister, while the rest of them went to the countryside.

The Afghan countryside had been a war zone for a decade, and the fleeing boy saw its scars everywhere – burnt-out tanks, abandoned trenches, villages where every family carried a story of loss.

Near one small settlement was a martyrs’ cemetery. Whenever villagers walked past, they would knock on the gravestones and shout: “Congratulations! Islam has become victorious. We have defeated the Russians.”

“For a boy my age, it was powerful,” he says. “Their pride, their certainty – it fascinated me.”

open image in galleryA martyrs’ cemetery with an Arab fighter’s grave in Kharote village of Maidaan-Shar (Supplied)

open image in galleryA martyrs’ cemetery with an Arab fighter’s grave in Kharote village of Maidaan-Shar (Supplied)Several months later, a ceasefire was declared in Kabul. Hoping to reunite with their father and sister, Banayee – then in his early teens – and his brother walked back to their home. They stayed two or three weeks. Then the ceasefire collapsed overnight, trapping them in one of the most brutal phases of the civil war.

“I saw the best and worst of humanity,” he says. “It changed me forever.”

Eventually, the family fled again, this time to Pakistan.

They ended up in one of the more than 150 refugee camps near Peshawar, sprawling settlements where life was defined by poverty, social conservatism and a labyrinth of madrasas. His Shamshatoo refugee camp was where Osama bin Laden recruited the soldiers for Al Qaeda.

Banayee recalls hearing that there were about 700 madrasas at the start of the Afghan jihad and by the time the Soviets withdrew the number had exploded to nearly 35,000, many supported directly by Pakistan’s intelligence services and indirectly by Western powers eager to use political Islam against communism.

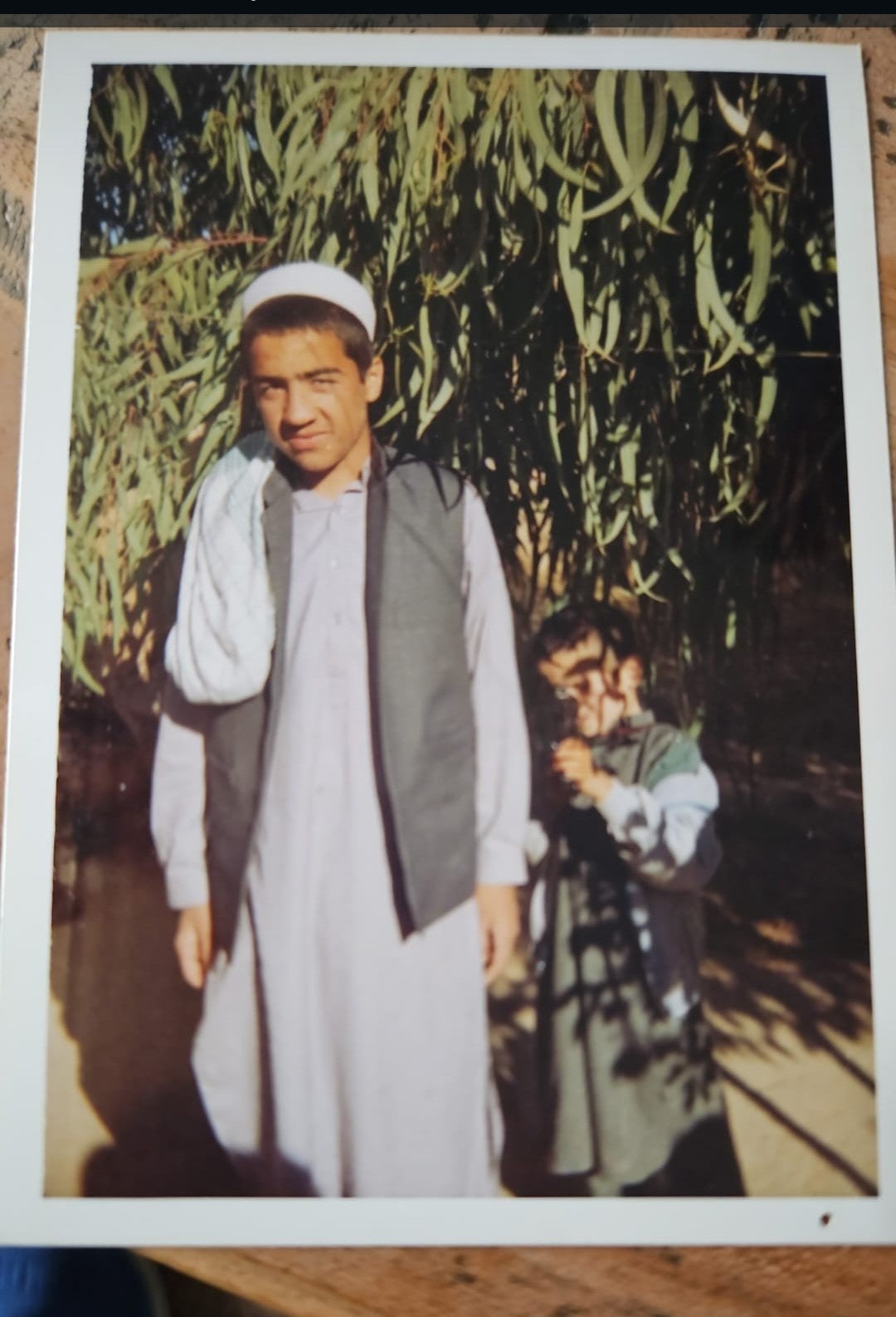

open image in galleryMaiwand Banayee aged 12 (Supplied)

open image in galleryMaiwand Banayee aged 12 (Supplied)“In the madrasa, martyrs were lionised,” Banayee says. “Suicide bombers were heroes. And I was brainwashed into believing the entire West was evil, savage and responsible for Muslim suffering.”

At first, he found comfort in religion. But slowly, faith hardened into something rigid and punitive – entirely consumed by jihad, sacrifice and the afterlife.

By 1996, when the Taliban seized Kabul, Banayee was burning with a desire to fight. “My greatest wish was martyrdom,” he says.

Still only a teenager, he travelled to Maidan Shahr, where his cousins were fighting with the Taliban. He took a gun and prepared to join fighting against the Northern Alliance, until his father tracked him down, quarrelled with the cousins, and dragged him home.

But the pull of jihad was strong. He ran away again, hoping to gain admission to Darul Uloom Haqqania, the infamous “University of Jihad”, alma mater of numerous Taliban leaders. Admissions were closed for the year, but he signed up for the next intake.

By then, he had learned to shoot guns and use rocket launchers. He walked with a gun slung across his shoulder and “felt really important”.

open image in gallery(Maiwand Banayee, aged 14, after fleeing to Shamshatoo refugee camp in Pakistan)

open image in gallery(Maiwand Banayee, aged 14, after fleeing to Shamshatoo refugee camp in Pakistan)But as fate would have it, Banayee encountered a series of events on his journey to join the Taliban officially that put the first cracks in his worldview.

He was stopped repeatedly by Taliban fighters at checkpoints, with a first group asking him to pray.

When Banayee said he had already done it, one fighter threatened to “bury 30 bullets” in his stomach if he spoke again.

“It hurt my ego,” he says. “They preached dignity, but they treated us with humiliation.”

At Kabul’s Ghazi Stadium, he witnessed a man forced to execute his brother’s killer and two alleged thieves having their hands amputated. “I closed my eyes. None of it felt like the Islam I believed in,” he says.

Another day, after his turban blew off on a journey, Taliban fighters accused him of imitating infidels. “They said I was humiliating the Prophet. It made no sense.” Each moment like that chipped away at his idealism.

open image in galleryMaiwand Banayee trained in martial arts during his time in a refugee camp in Pakistan (Supplied)

open image in galleryMaiwand Banayee trained in martial arts during his time in a refugee camp in Pakistan (Supplied)While Banayee was waiting for the next Haqqania admission round, his father pushed him to “do something with his life”.

To keep him quiet, Banayee enrolled in a secular school in Peshawar, a decision that would ultimately change his life.

The school was a different world: boys from affluent families who shaved, watched Western and Indian films, and talked freely.

“I resented them at first,” he says. “They were everything I had been taught to despise.”

Over time, he began to enjoy their company. Questions took root. Broader thinking challenged religious dogma. “Slowly, slowly, my faith in that version of Islam eroded.”

Looking back, he can clearly see the radicalisation machinery of the seminary: a “jihadist curriculum”, freelance mullahs, myths about martyrdom, and relentless propaganda.

His indoctrination was so deep that he once smashed his father’s newly purchased television, convinced it was immoral. “We were told people who owned a TV were pimps for their mothers and sisters because women would fantasise about actors.”

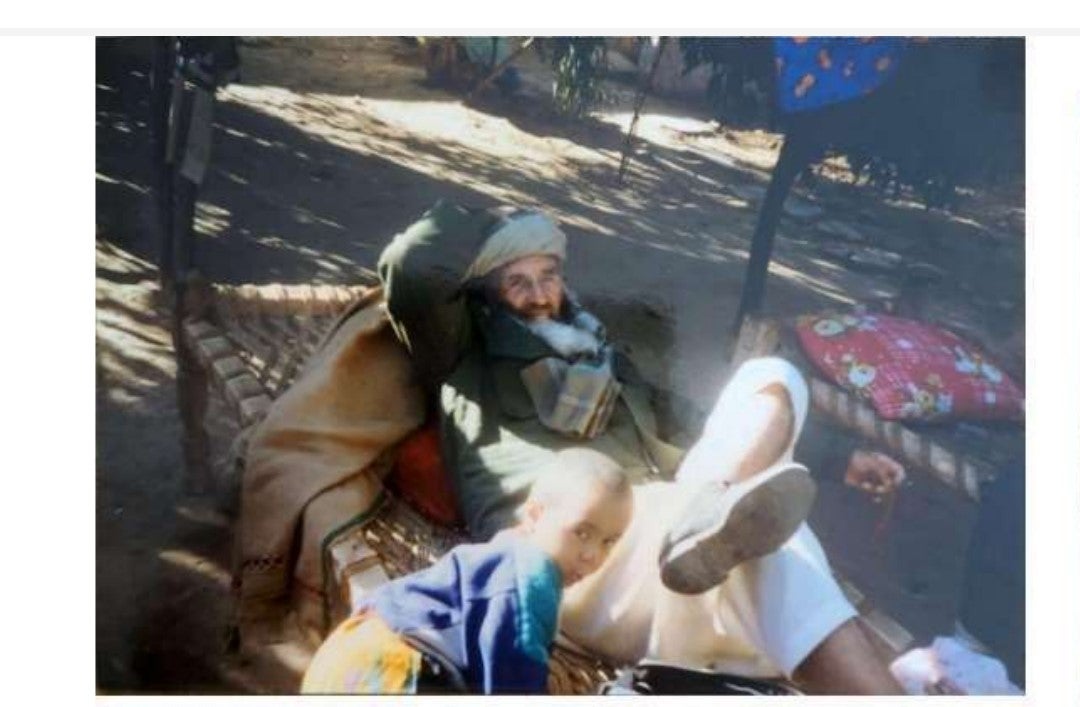

open image in galleryMaiwand Banayee's father resting at his house in the Shamshatoo refugee camp (Supplied)

open image in galleryMaiwand Banayee's father resting at his house in the Shamshatoo refugee camp (Supplied)In the Afghanistan of Banayee’s early years, women were always “covered from head to toe and couldn’t travel without male guardians”.

“The situation for women is even bleaker and more horrifying now,” he says, “and this is the 21st century we’re talking about.”

The turning point arrived in 2001. After the September 11 attacks, Pakistan’s military rulers allowed the US to use its soil to strike Afghanistan. Some boys from the refugee camp protested and attacked a police checkpoint. Rumours spread that the Pakistani spy agency was looking for those involved. Banayee had not participated but his name surfaced by association. Fearing arrest at a time when anyone suspected of extremism was being rounded up, he fled.

open image in galleryMaiwand Banayee works as a NHS diabetes remission coach (Supplied)

open image in galleryMaiwand Banayee works as a NHS diabetes remission coach (Supplied)His first attempt to flee landed him in a Lahore prison for three months after he was caught travelling without a passport.

After his release, Banayee contacted travel agents who flew him without valid papers from Peshawar to Dubai, gave him a forged Pakistani passport there, transported him to Russia, where he was kept in a room for a month, and finally took him to the UK.

Reflecting back, Banayee says he feels “sorry” for that boy. “I was green, desperate and poor, and so naive.”

After arriving in England in 2002, Banayee taught himself English and worked towards a better life.

Maiwand Banayee’s memoir Delusions of Paradise: Escaping the Life of a Taliban Fighter was published by Icon Books in April 2025.

More about

TalibanKabulAfghanistanPakistanJoin our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments