- Archaeology

A novel biochemical analysis of a Renaissance medical text has successfully recovered centuries-old proteins that might be from lizards and hippos.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

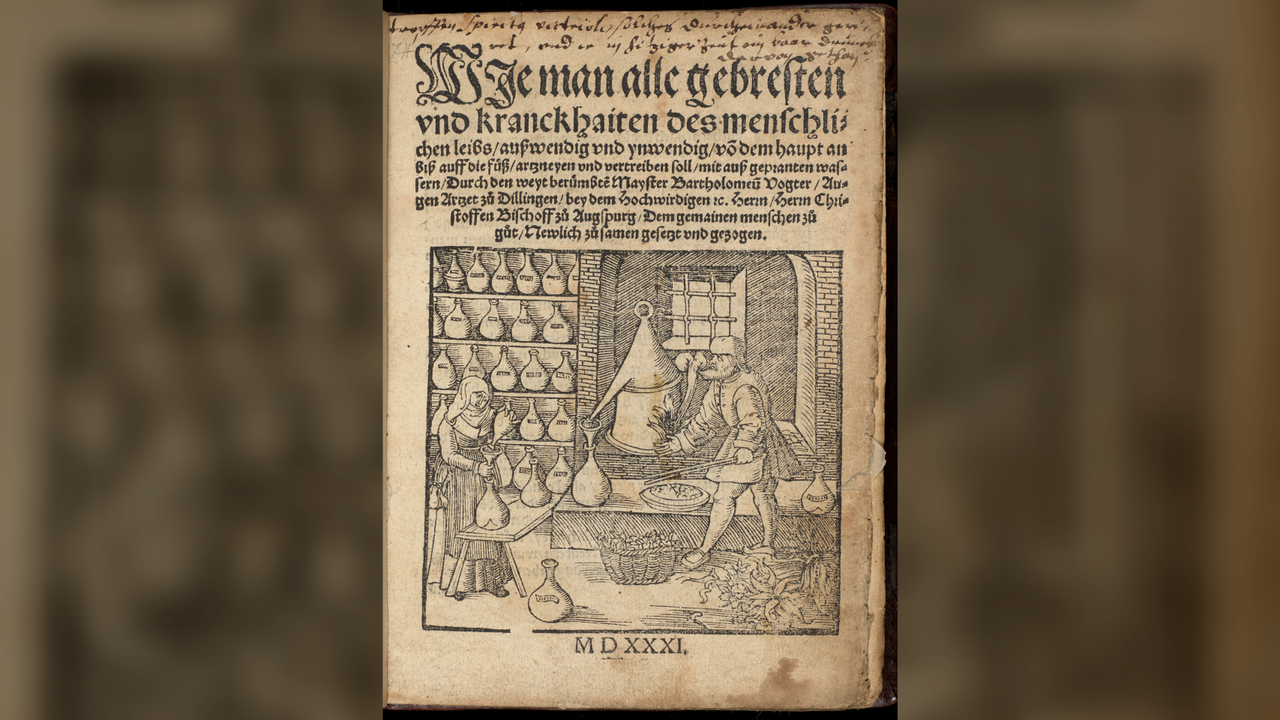

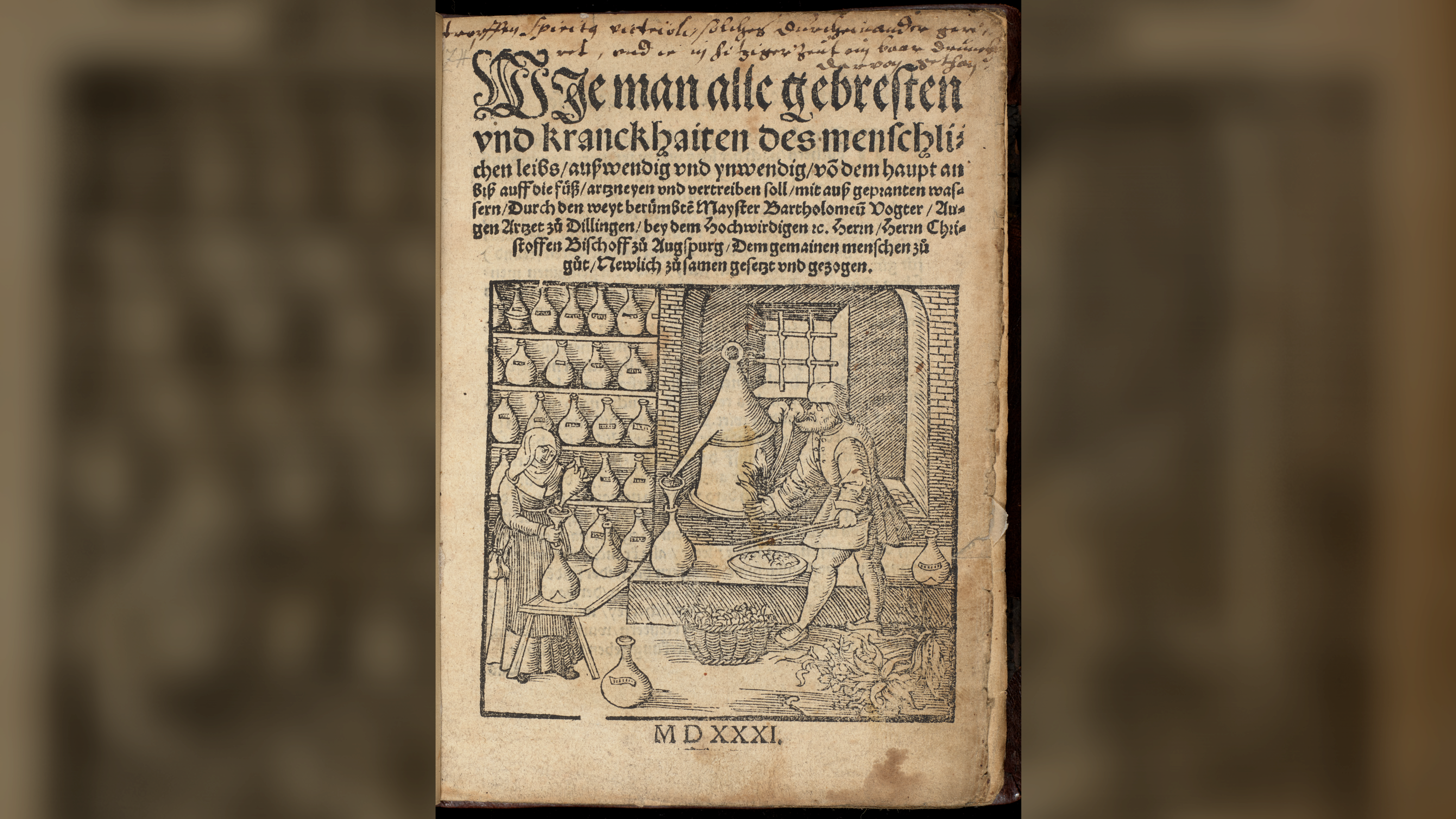

The title page of a collection of Renaissance German medical recipes published in 1531 by Bartholomäus Vogtherr.

(Image credit: Image provided by The John Rylands Research Institute and Library, The University of Manchester)

Share

Share by:

The title page of a collection of Renaissance German medical recipes published in 1531 by Bartholomäus Vogtherr.

(Image credit: Image provided by The John Rylands Research Institute and Library, The University of Manchester)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Folk medicine practitioners in 16th-century Europe left ingredients and fingerprints smudged on their manuals while developing remedies for minor ailments. Now, researchers are studying the chemical traces Renaissance people left behind to understand how they experimented with novel cures.

Two German medical manuals — "How to Cure and Expel All Afflictions and Illnesses of the Human Body" and "A Useful and Essential Little Book of Medicine for the Common Man" — were published in 1531 by eye doctor Bartholomäus Vogtherr. His systematically gathered recipe books for common ailments, like hair loss and bad breath, quickly became bestsellers in Renaissance domestic medicine.

You may like-

Leonardo da Vinci's DNA may be embedded in his art — and scientists think they've managed to extract some

Leonardo da Vinci's DNA may be embedded in his art — and scientists think they've managed to extract some

-

'They had not been seen ever before': Romans made liquid gypsum paste and smeared it over the dead before burial, leaving fingerprints behind, new research finds

'They had not been seen ever before': Romans made liquid gypsum paste and smeared it over the dead before burial, leaving fingerprints behind, new research finds

-

Tooth-in-eye surgery, 'blood chimerism,' and a pregnancy from oral sex: 12 wild medical cases we covered in 2025

Tooth-in-eye surgery, 'blood chimerism,' and a pregnancy from oral sex: 12 wild medical cases we covered in 2025

In a study published Nov. 19 in the journal American Historical Review, researchers reported their success at using proteomics analysis to identify the materials that medical practitioners were using as they flipped through Vogtherr's book centuries ago.

"People always leave molecular traces on the pages of books and other documents when they come into contact with paper," study co-author Gleb Zilberstein, a biotechnology expert and inventor, told Live Science in an email. "These traces include components of sweat, sometimes saliva, metabolites, contaminants, and environmental components." Proteins and peptides are part of this mixture and are "often invisible to the naked eye," Zilberstein added.

To analyze the proteins and peptides (molecules made up of strings of amino acids), the researchers first used specially made plastic diskettes to capture the proteins from the paper. Then, they used mass spectrometry to detect individual amino-acid chains that could be identified as specific proteins.

In total, the researchers sequenced 111 proteins from the Vogtherr manual. Most of the proteins were from the practitioners themselves, the team wrote in the study, but several were associated with plants or animals that were featured in the curative recipes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over."Peptide traces of European beech, watercress, and rosemary were recovered next to recipes recommending the use of these plants to cure hair loss and to strengthen the growth of facial and head hair," the researchers wrote, and "lipocalin recovered next to a recipe that recommends the everyday use of human feces to wash one's bald head for overcoming hair loss points to reader-practitioners following such instructions."

Other collagen peptides were harder to identify. One extracted protein could match either tortoise shell or lizards. While 16th-century medical literature mentions that turtle shells were reported to cure edema (fluid retention), pulverized lizard heads were used to prevent hair loss. But the protein was discovered on a page next to Vogtherr's hair-growth recipes, suggesting that the user of the medical manual may have experimented with lizards as hair-care therapy.

Another surprising discovery was the recovery of collagen peptides that may match a hippopotamus next to recipes discussing ailments of the mouth and scalp. Hippos were a popular curiosity across early modern Europe, and their teeth were thought to cure baldness, severe dental problems and kidney stones. The traces of hippo proteins may suggest that Vogtherr's readers struggled with tooth issues, the researchers wrote, as recipes to cure stinking breath, mouth ulcers and black teeth are dog-eared and annotated in the manual.

RELATED STORIES—Leonardo da Vinci's DNA may be embedded in his art — and scientists think they've managed to extract some

—'Complete lack of sunlight' killed a Renaissance-era toddler, CT scan reveals

—'Exceptional' Renaissance armor stolen from the Louvre 40 years ago is finally returned

"Proteomics help contextualize both the symptoms that people possibly struggled with when turning to recipe knowledge for help and the bodily effects of recipe trials and treatments," the researchers wrote.

The scientists hope their novel analysis of invisible proteins clinging to centuries-old books will contribute to a better understanding of early modern household science.

"In the future, we plan to expand this work and examine other historical books," Zilberstein said, as well as "to identify individual readers based on their proteomic data."

Conspiracy theory quiz: Test your knowledge of unfounded beliefs, from flat Earth to lizard people

TOPICS science Kristina KillgroveSocial Links NavigationStaff writer

Kristina KillgroveSocial Links NavigationStaff writerKristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more 'They had not been seen ever before': Romans made liquid gypsum paste and smeared it over the dead before burial, leaving fingerprints behind, new research finds

'They had not been seen ever before': Romans made liquid gypsum paste and smeared it over the dead before burial, leaving fingerprints behind, new research finds

Tooth-in-eye surgery, 'blood chimerism,' and a pregnancy from oral sex: 12 wild medical cases we covered in 2025

Tooth-in-eye surgery, 'blood chimerism,' and a pregnancy from oral sex: 12 wild medical cases we covered in 2025

'Biological time capsules': How DNA from cave dirt is revealing clues about early humans and Neanderthals

'Biological time capsules': How DNA from cave dirt is revealing clues about early humans and Neanderthals

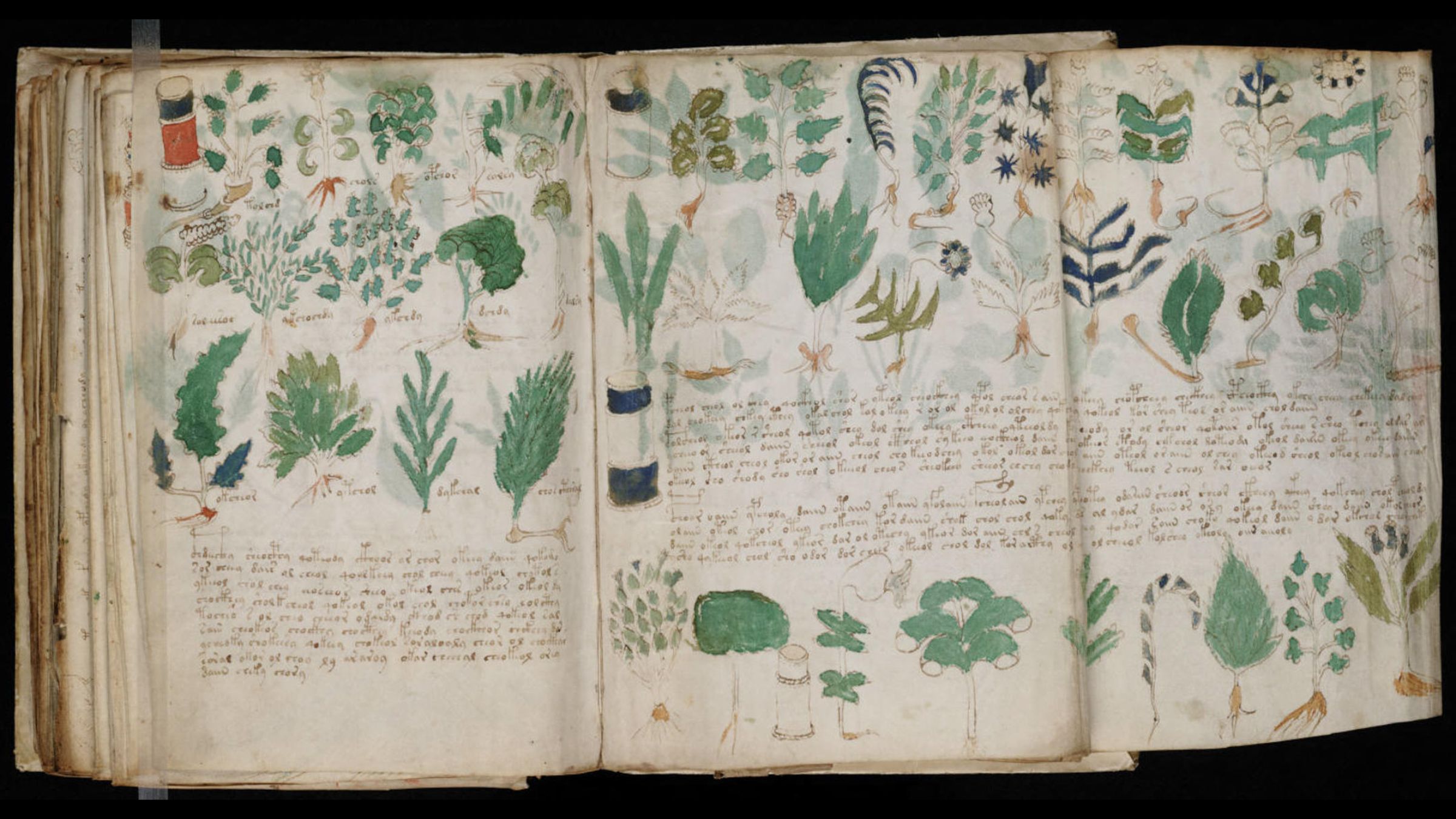

Mysterious Voynich manuscript may be a cipher, a new study suggests

Mysterious Voynich manuscript may be a cipher, a new study suggests

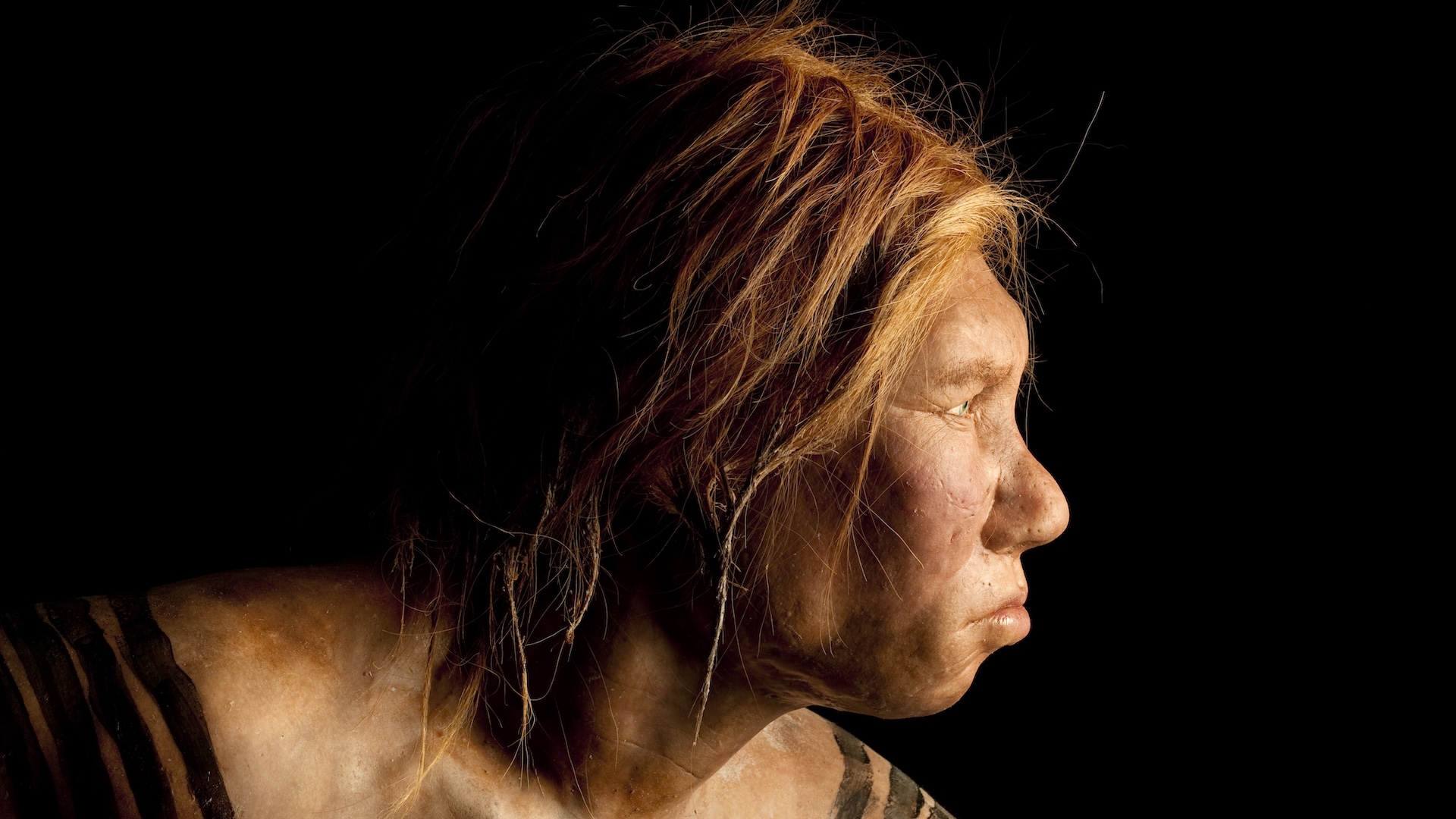

Neanderthals were more susceptible to lead poisoning than humans — which helped us gain an advantage over our cousins, scientists say

Neanderthals were more susceptible to lead poisoning than humans — which helped us gain an advantage over our cousins, scientists say

Centuries-old 'trophy head' from Peru reveals individual survived to adulthood despite disabling birth defect

Latest in Archaeology

Centuries-old 'trophy head' from Peru reveals individual survived to adulthood despite disabling birth defect

Latest in Archaeology

5,500-year-old human skeleton discovered in Colombia holds the oldest evidence yet that syphilis came from the Americas

5,500-year-old human skeleton discovered in Colombia holds the oldest evidence yet that syphilis came from the Americas

2.6 million-year-old jaw from extinct 'Nutcracker Man' is found where we didn't expect it

2.6 million-year-old jaw from extinct 'Nutcracker Man' is found where we didn't expect it

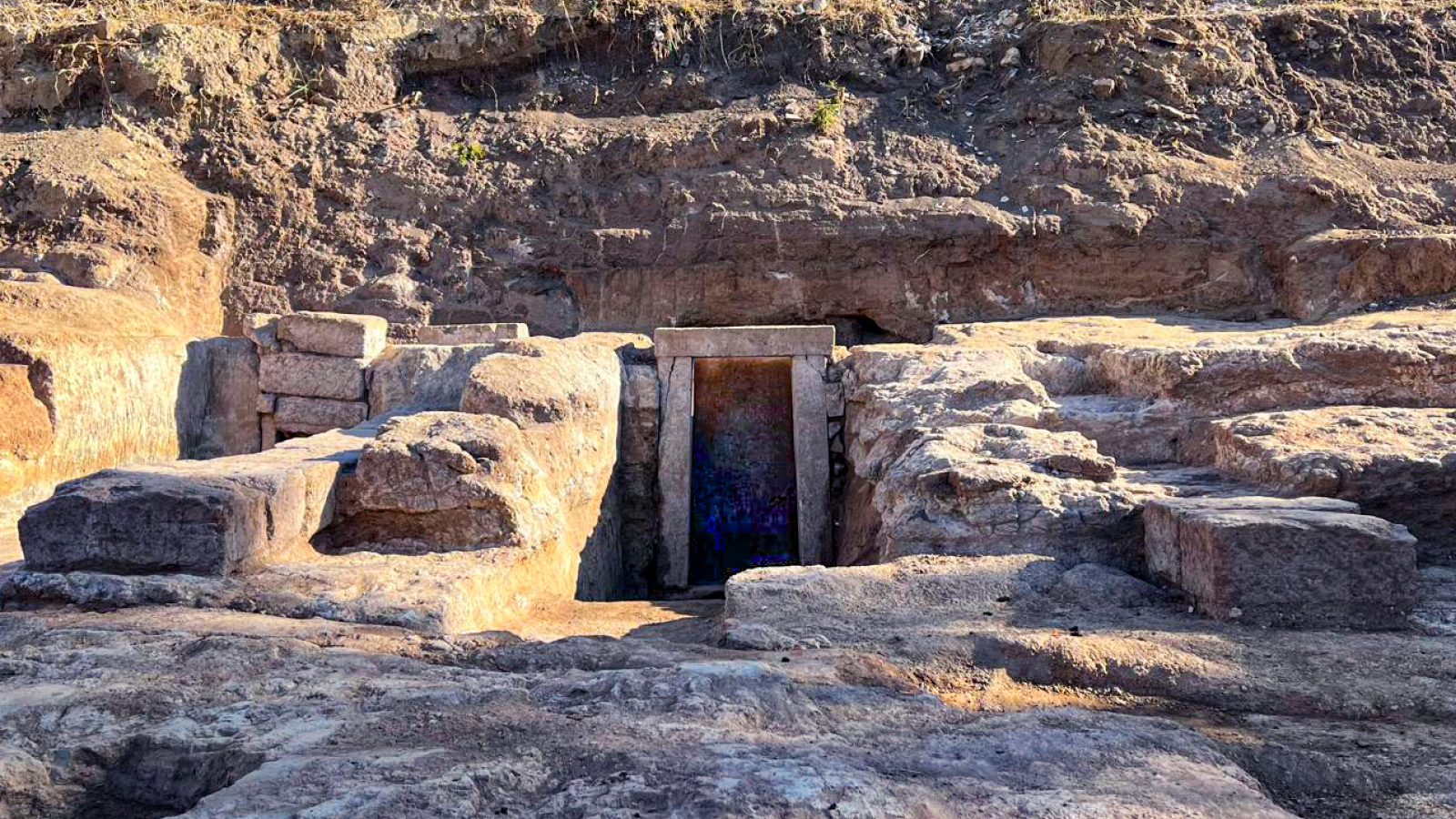

2,400-year-old Hercules shrine and elite tombs discovered outside ancient Rome's walls

2,400-year-old Hercules shrine and elite tombs discovered outside ancient Rome's walls

World's oldest known rock art predates modern humans' entrance into Europe — and it was found in an Indonesian cave

World's oldest known rock art predates modern humans' entrance into Europe — and it was found in an Indonesian cave

Medieval 'super ship' found wrecked off Denmark is largest vessel of its kind

Medieval 'super ship' found wrecked off Denmark is largest vessel of its kind

Romans regularly soaked in filthy, lead-contaminated bath water, Pompeii study finds

Latest in News

Romans regularly soaked in filthy, lead-contaminated bath water, Pompeii study finds

Latest in News

Wegovy now comes in pill form — here's how it works

Wegovy now comes in pill form — here's how it works

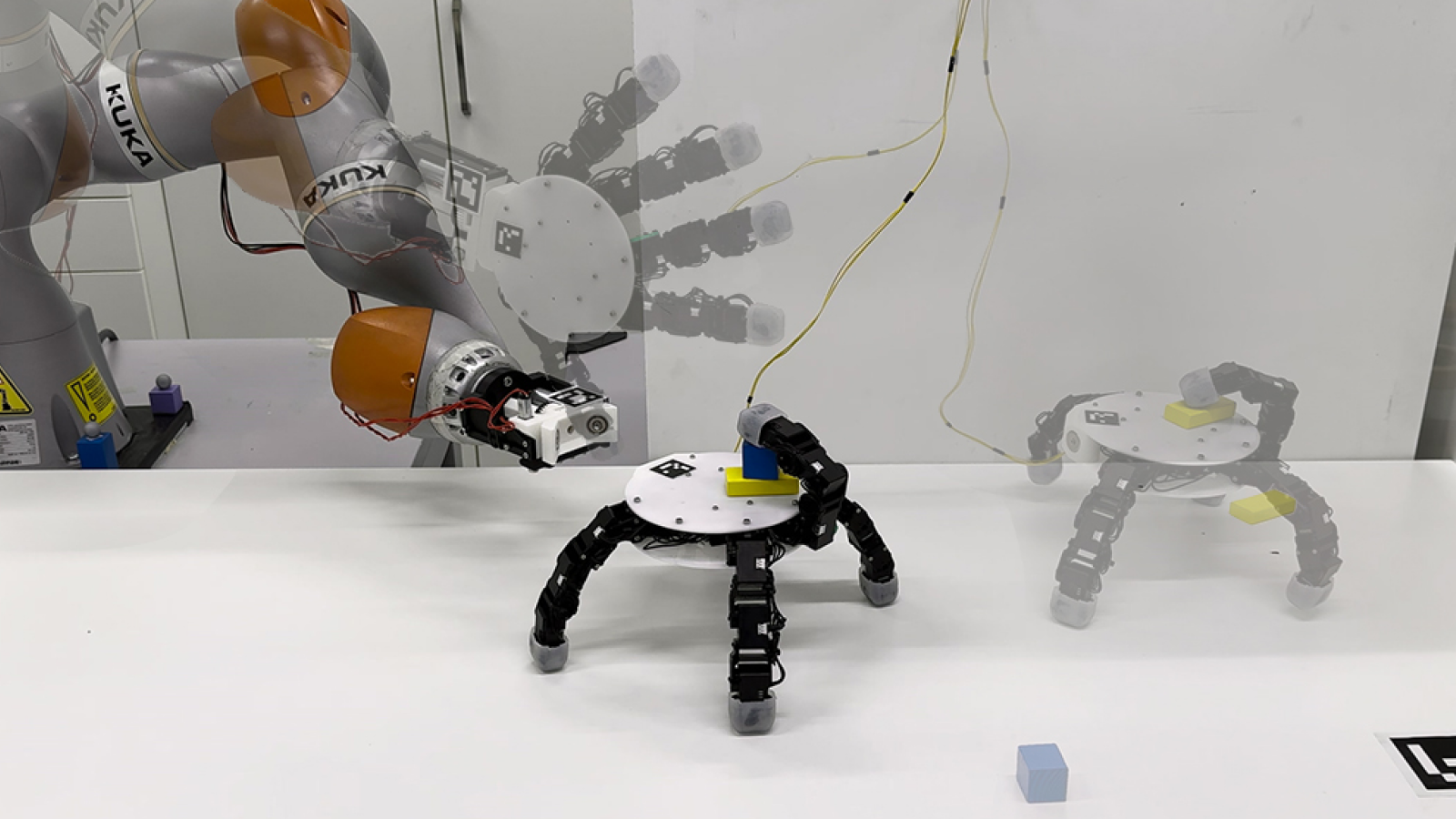

Creepy robotic hand detaches at the wrist before scurrying away to collect objects

Creepy robotic hand detaches at the wrist before scurrying away to collect objects

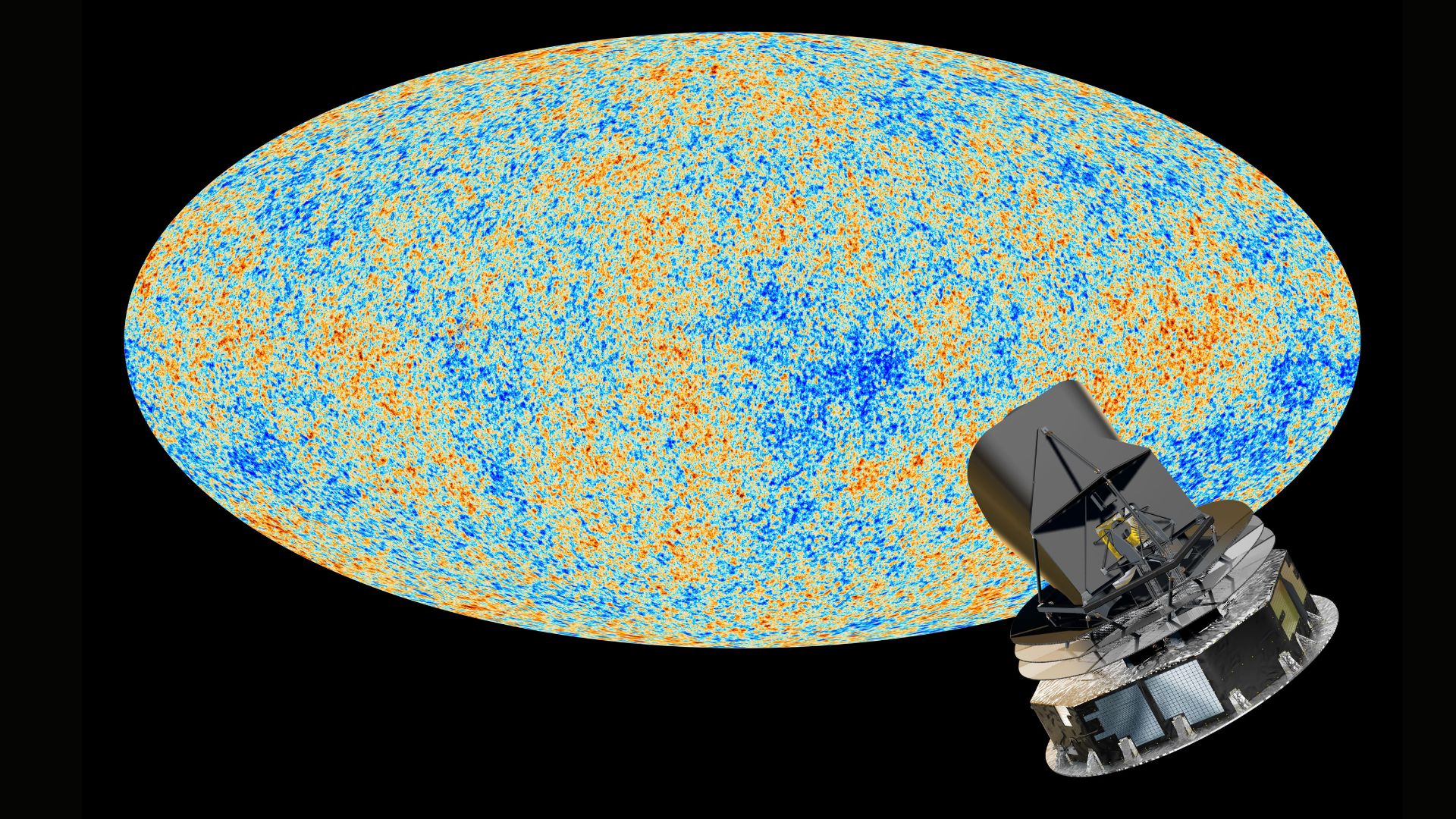

Dark matter and neutrinos may interact, hinting at 'fundamental breakthrough' in particle physics

Dark matter and neutrinos may interact, hinting at 'fundamental breakthrough' in particle physics

Lab mice that 'touch grass' are less anxious — and that highlights a big problem in rodent research

Lab mice that 'touch grass' are less anxious — and that highlights a big problem in rodent research

Californians have been using far less water than suppliers estimated — what does this mean for the state?

Californians have been using far less water than suppliers estimated — what does this mean for the state?

Coyote scrambles onto Alcatraz Island after perilous, never-before-seen swim

LATEST ARTICLES

Coyote scrambles onto Alcatraz Island after perilous, never-before-seen swim

LATEST ARTICLES 15,500-year-old human skeleton discovered in Colombia holds the oldest evidence yet that syphilis came from the Americas

15,500-year-old human skeleton discovered in Colombia holds the oldest evidence yet that syphilis came from the Americas- 2Wegovy now comes in pill form — here's how it works

- 3Creepy robotic hand detaches at the wrist before scurrying away to collect objects

- 4Sega Toys Homestar Classic star projector review

- 56 tips to kickstart your exercise routine and actually stick to it, according to science