- Planet Earth

A switch from a humid to a dry climate has led the Eastern African Rift Zone to pull apart more freely, new research finds.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

(Image credit: Paul & Paveena Mckenzie/Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

(Image credit: Paul & Paveena Mckenzie/Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Over the past 5,000 years, East Africa has dried out. Now, new research finds that this change may be making the continent pull apart faster.

Faults in the East African Rift Zone have sped up since the levels of large lakes have dropped, according to research published in November in the journal Scientific Reports.

You may like-

A gulf separating Africa and Asia is still pulling apart — 5 million years after scientists thought it had stopped

A gulf separating Africa and Asia is still pulling apart — 5 million years after scientists thought it had stopped

-

Eruptions of ocean volcanoes may be the echoes of ancient continental breakups

Eruptions of ocean volcanoes may be the echoes of ancient continental breakups

-

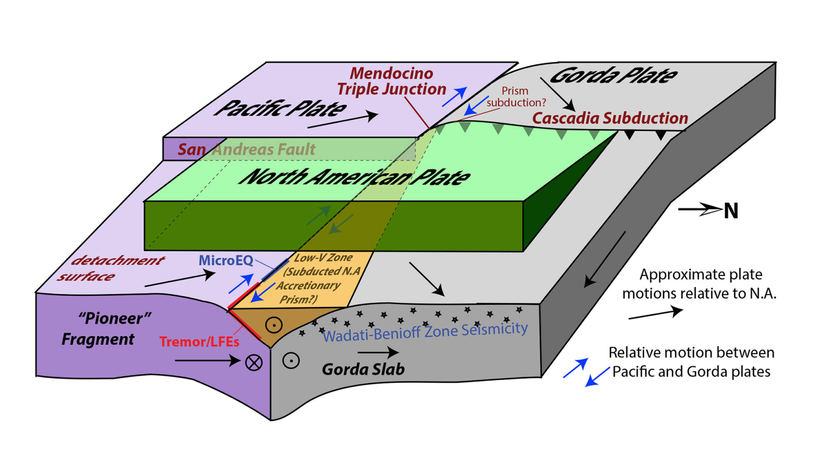

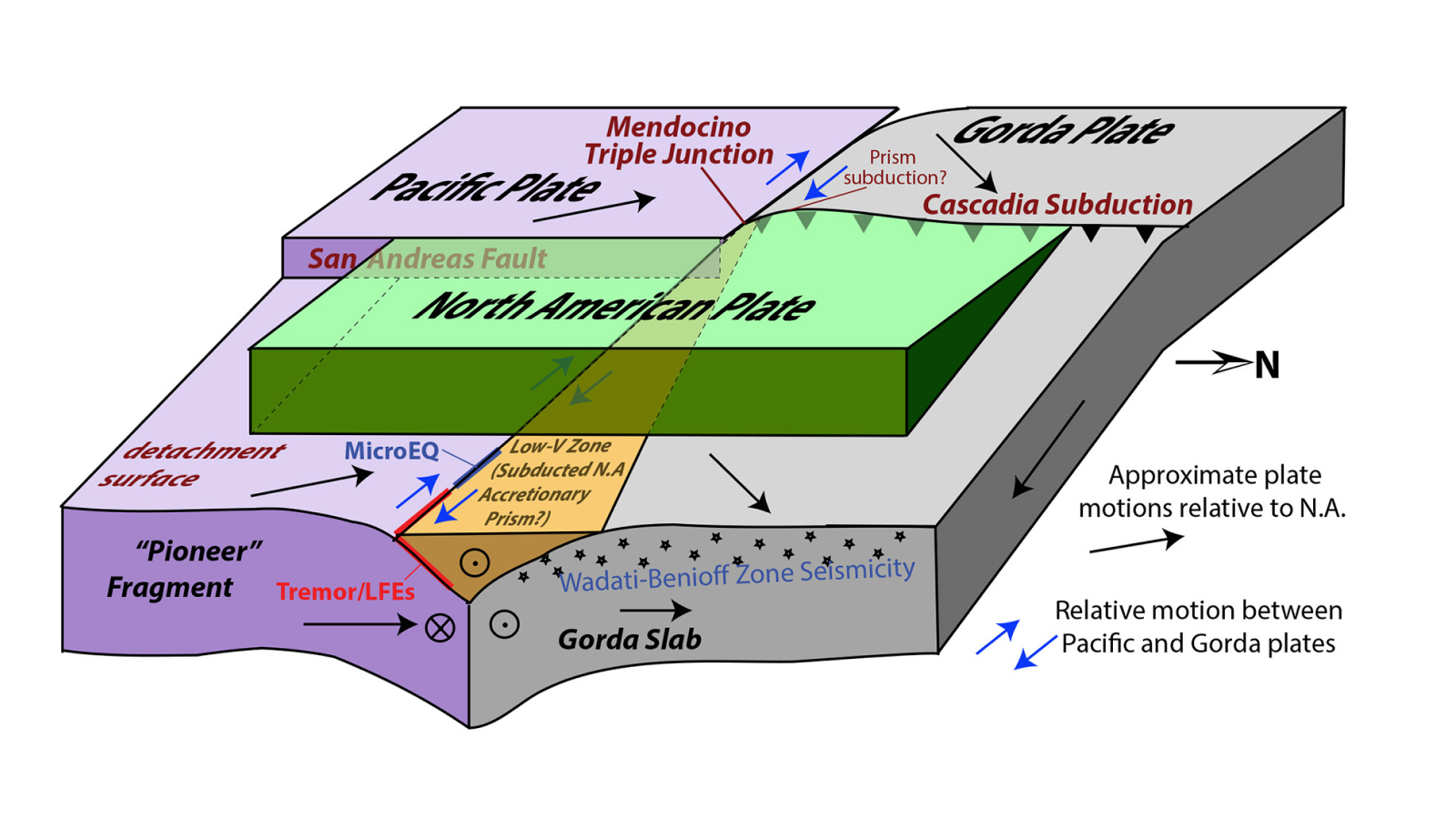

Fragment of lost tectonic plate discovered where San Andreas and Cascadia faults meet

Fragment of lost tectonic plate discovered where San Andreas and Cascadia faults meet

"Usually it is something we think about the other way around: Mountains build, and that changes the local or regional climate," Scholz told Live Science. "But it can work the other way around too."

Scholz and his colleagues conducted their research at Lake Turkana in Kenya, which is 155 miles (250 kilometers) long, 19 miles (30 km) wide, and up to 400 feet (120 meters) deep in places. That's nothing, however, compared with the level more than 5,000 years ago, when the lake was up to 500 feet (150 m) deeper.

That was during the African Humid Period, when much of Africa was wetter than it is today. In East Africa, this period persisted from about 9,600 years ago to 5,300 years ago, with drier conditions prevailing over the past 5,300 years. The researchers studied lake-bed sediments to determine ancient water levels and sediment flows into Lake Turkana. In the process, they noticed many small faults and the fingerprints of long-ago earthquakes in the sediments.

The tectonic plate that underlies Africa is pulling apart in eastern Africa and may one day split into two plates with an ocean between them. The deep, narrow lakes in the region — including Lake Turkana and nearby waterways, such as Lake Malawi in Tanzania and Mozambique —, are the result of this rifting process, which is creating a deep valley in the region.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.Scholz and his team wanted to know if the changes in the lakes themselves were influencing this rifting process. Water matters to tectonics: When glaciers retreat, for example, the lifting of their weight actually causes the land beneath to spring up like rising bread — a process called isostatic rebound. Large amounts of water similarly press down on the crust beneath, potentially affecting processes like earthquakes.

The researchers found that after the end of the African Humid Period, the faults in Lake Turkana began to move faster, at an average rate of 0.007 inches (0.17 millimeters) of extra movement per year. In general, Africa is rifting apart at 0.25 inches (6.35 millimeters) per year.

Using computer simulations, the researchers figured out that this seismic speedup likely has two causes. One is that with less water pressing down on the crust, the faults have more freedom to move: Imagine a vise loosening around two slabs of wood. The other cause is more indirect. On an island in the south side of Lake Turkana is a volcano with an active magma chamber. The removal of water from the African Humid Period decompresses the mantle under this volcano, leading to more melting. That melt, in turn, moves into the volcano's magma chamber, inflating it and leading to more tectonic activity on nearby fault lines.

RELATED STORIES—Africa is being torn apart by a 'superplume' of hot rock from deep within Earth, study suggests

—A gulf separating Africa and Asia is still pulling apart — 5 million years after scientists thought it had stopped

—Lake Kivu: The ticking time bomb that could one day explode

"We see enhanced faulting during this time interval, so more pronounced earthquakes are presumably prevalent in this broader region now compared to 8,000 years ago," Scholz said.

The researchers are now working on a project at Lake Malawi looking at water level changes going back 1.4 million years, hoping to get a better sense of how the climate affects the separation of continents.

"This information about these huge changes in water volumes in these lakes is a really important part of the story," Scholz said.

Article SourcesMuirhead, J. D., Xue, L., Moucha, R., Paciga, M. K., Judd, E. J., & Scholz, C. A. (2025). Accelerated rifting in response to regional climate change in the East African Rift System. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 38833. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23264-9

TOPICS news explainers Stephanie PappasSocial Links NavigationLive Science Contributor

Stephanie PappasSocial Links NavigationLive Science ContributorStephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Eruptions of ocean volcanoes may be the echoes of ancient continental breakups

Eruptions of ocean volcanoes may be the echoes of ancient continental breakups

Fragment of lost tectonic plate discovered where San Andreas and Cascadia faults meet

Fragment of lost tectonic plate discovered where San Andreas and Cascadia faults meet

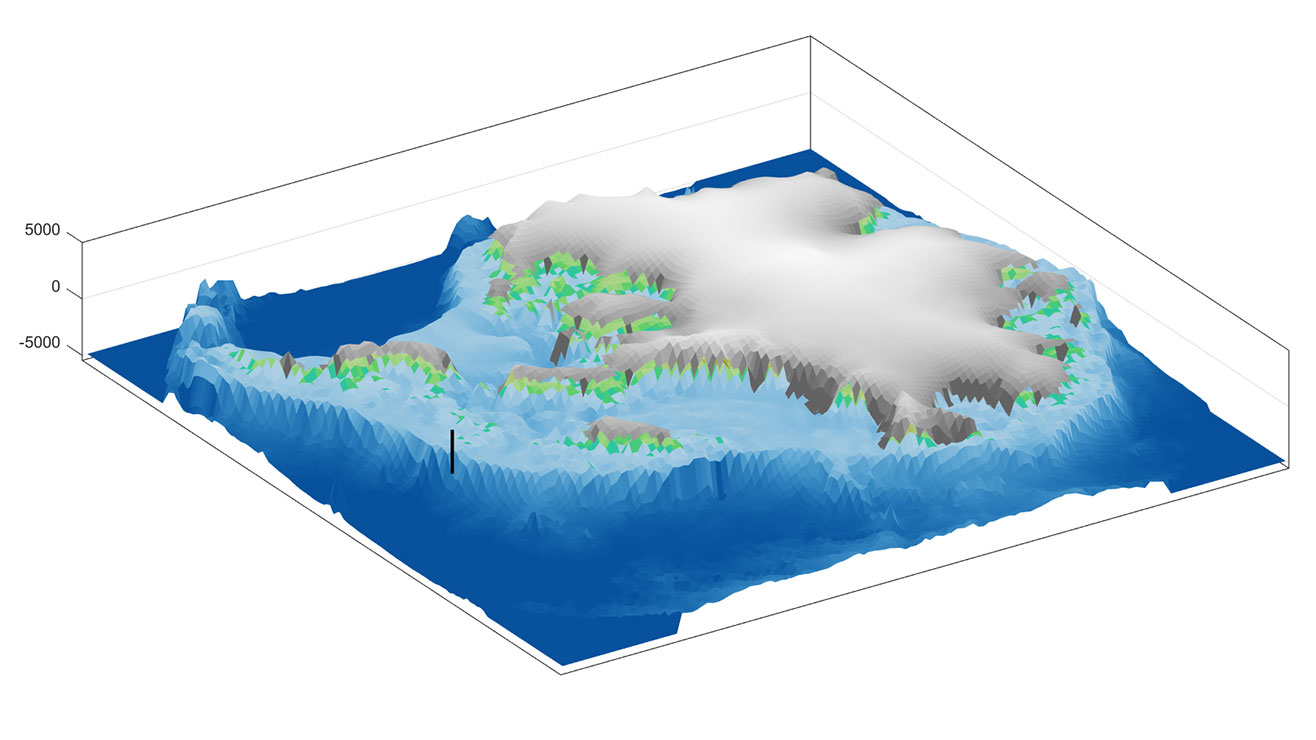

Melting of West Antarctic ice sheet could trigger catastrophic reshaping of the land beneath

Melting of West Antarctic ice sheet could trigger catastrophic reshaping of the land beneath

Ruptures from 'silent' earthquakes deep in Earth's crust can heal themselves within hours

Ruptures from 'silent' earthquakes deep in Earth's crust can heal themselves within hours

Collapse of key Atlantic current could bring extreme drought to Europe for hundreds of years, study finds

Collapse of key Atlantic current could bring extreme drought to Europe for hundreds of years, study finds

18 of Earth's biggest river deltas — including the Nile and Amazon — are sinking faster than global sea levels are rising

Latest in Planet Earth

18 of Earth's biggest river deltas — including the Nile and Amazon — are sinking faster than global sea levels are rising

Latest in Planet Earth

Critical moment when El Niño started to erode Russia's Arctic sea ice discovered

Critical moment when El Niño started to erode Russia's Arctic sea ice discovered

'Doomsday Clock' ticks 4 seconds closer to midnight

'Doomsday Clock' ticks 4 seconds closer to midnight

Ancient lake full of crop circles lurks in the shadow of Saudi Arabia's 'camel-hump' mountain

Ancient lake full of crop circles lurks in the shadow of Saudi Arabia's 'camel-hump' mountain

Thousands of dams in the US are old, damaged and unable to cope with extreme weather. How bad is it?

Thousands of dams in the US are old, damaged and unable to cope with extreme weather. How bad is it?

Arctic blast probably won't cause trees to explode in the cold — but here's what happens if and when they do go boom

Arctic blast probably won't cause trees to explode in the cold — but here's what happens if and when they do go boom

Chocolate Hills: The color-changing mounds in the Philippines that inspired legends of mud-slinging giants

Latest in News

Chocolate Hills: The color-changing mounds in the Philippines that inspired legends of mud-slinging giants

Latest in News

New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds

New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds

'Part of the evolutionary fabric of our societies': Same-sex sexual behavior in primates may be a survival strategy, study finds

'Part of the evolutionary fabric of our societies': Same-sex sexual behavior in primates may be a survival strategy, study finds

More than 43,000 years ago, Neanderthals spent centuries collecting animal skulls in a cave; but archaeologists aren't sure why

More than 43,000 years ago, Neanderthals spent centuries collecting animal skulls in a cave; but archaeologists aren't sure why

Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.

Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.

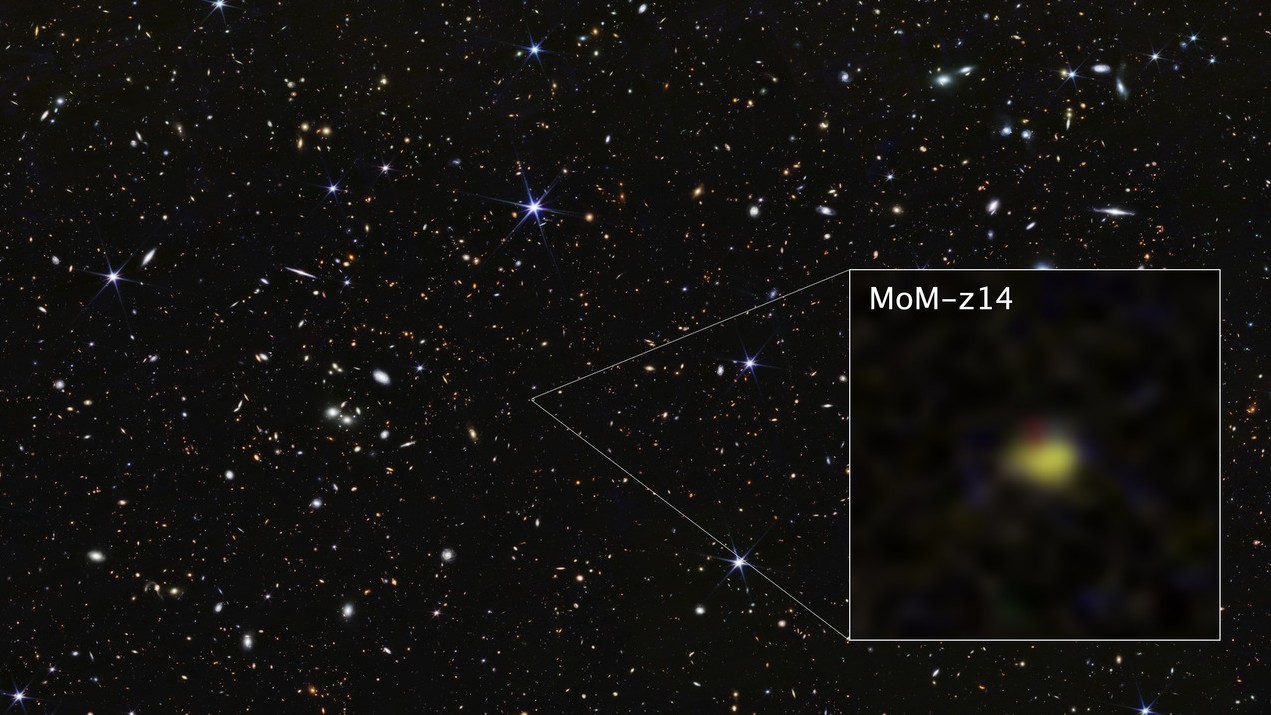

James Webb telescope breaks own record, discovering farthest known galaxy in the universe

James Webb telescope breaks own record, discovering farthest known galaxy in the universe

South Carolina's measles outbreak nears 790 cases — making it the biggest in decades

LATEST ARTICLES

South Carolina's measles outbreak nears 790 cases — making it the biggest in decades

LATEST ARTICLES 1New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds

1New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds- 2Thousands of dams in the US are old, damaged and unable to cope with extreme weather. How bad is it?

- 3'Part of the evolutionary fabric of our societies': Same-sex sexual behavior in primates may be a survival strategy, study finds

- 4More than 43,000 years ago, Neanderthals spent centuries collecting animal skulls in a cave; but archaeologists aren't sure why

- 5Watch awkward Chinese humanoid robot lay it all down on the dance floor