- Archaeology

- Human Evolution

Neanderthals repeatedly returned to the cave to store horned animal skulls, revealing this cultural tradition was transmitted over time.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

Neanderthals carefully placed the skulls of steppe bison (a – f), aurochs (g), rhinos (h, i) and red deer (j, k) in a cave in what is now Spain

(Image credit: Baquedano et al. Nature Human Behaviour (2023) CC-BY-4.0)

Share

Share by:

Neanderthals carefully placed the skulls of steppe bison (a – f), aurochs (g), rhinos (h, i) and red deer (j, k) in a cave in what is now Spain

(Image credit: Baquedano et al. Nature Human Behaviour (2023) CC-BY-4.0)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Neanderthals purposefully collected and positioned horned and antlered animal skulls in a cave in what is now Spain, suggesting that these extinct human relatives had complex cultural practices over 43,000 years ago, a new study finds.

Des-Cubierta cave in central Iberia was initially discovered in 2009. In 2023, researchers announced the unusual discovery of an assortment of 35 large mammal skulls inside the cave. Most jaw bones were missing, but all skulls came from horned or antlered species like steppe bison and aurochs. Over 1,400 stone tools were uncovered in the same level, all in the Mousterian style typical of Neanderthals.

"At first glance, the deposit appears chaotic," study first author Lucía Villaescusa Fernández, a doctoral researcher in archaeology at the University of Alcalá in Spain, told Live Science in an email. "What initially looked like a disorganised accumulation of materials turned out to preserve a clear record of both geological processes and human activity," she said.

You may like-

'The images could be much older': Analysis of rocks shows Neanderthals made art at least 64,000 years ago

'The images could be much older': Analysis of rocks shows Neanderthals made art at least 64,000 years ago

-

Neanderthals cannibalized 'outsider' women and children 45,000 years ago at cave in Belgium

Neanderthals cannibalized 'outsider' women and children 45,000 years ago at cave in Belgium

-

Did Neanderthals have religious beliefs?

Did Neanderthals have religious beliefs?

The cave experienced many rockfalls in the millennia following its use, so Villaescusa Fernández and her team teased the role of these disturbances apart from the Neanderthal activity. This confirmed the Neanderthals were collecting animal skulls over a long period of time in particularly cold periods between 135,000 and 43,000 years ago, according to a study published Jan. 3 in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

"This distinction is essential in archaeology because understanding past human behaviour requires first identifying which parts of the archaeological record were created by people and which were shaped by nature," Villaescusa Fernández said.

To fill this gap, Villaescusa Fernández and her colleagues carefully mapped the location of all the archaeological remains. They then compared the rockfall debris distribution with that of the animal bones and stone tools. It became clear that the bones had been purposefully positioned within the cave. "These materials had different origins and were not introduced into the cave by the same processes," Villaescusa Fernández said.

Although the timescale cannot be directly measured, and the precise duration of the practice remains uncertain, the team also found the animal skulls had been placed in specific areas of the cave repeatedly over a prolonged period of time. This suggests that this practice may have been maintained over generations and was not directly tied to economic or subsistence needs, Villaescusa Fernández said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.RELATED STORIES—Crimean Stone Age 'crayons' were used by Neanderthals for symbolic drawings, study claims

—Paleolithic 'art sanctuary' in Spain contains more than 110 prehistoric cave paintings

—125,000-year-old 'fat factory' run by Neanderthals discovered in Germany

Exactly why Neanderthals collected the skulls is unclear, but the selection, treatment and placement of horned animal skulls in a cave they did not live in "highlights their capacity for cultural practices that are not directly related to survival," Villaescusa Fernández said. "This has important implications for how we understand Neanderthal societies, particularly in terms of cultural transmission and shared traditions," she added.

"Too often, discussions of Neanderthal symbolism rely on fragile evidence or optimistic interpretations," Ludovic Slimak, an archaeologist at the University of Toulouse in France and author of the book "The Naked Neanderthal" (Penguin, 2024) who was not involved in the study, told Live Science by email. "Here, the authors take a more grounded approach, testing whether the spatial organization of the remains could be explained by natural processes alone," he said.

Slimak said that the findings of this study add new evidence to the debate over Neanderthal symbolism. "Rather than asking whether Neanderthals were 'symbolic like us,' we should ask what kinds of meaningful behaviors they developed on their own terms. This site suggests that Neanderthal worlds of meaning existed, but they may have been structured very differently from those of Homo sapiens," he said.

Article SourcesVillaescusa, L., Baquedano, E., Martín-Perea, D. M., Márquez, B., Galindo-Pellicena, M. Á., Cobo-Sánchez, L., Ortega, A. I., Huguet, R., Laplana, C., Ortega, M. C., Gómez-Soler, S., Moclán, A., García, N., Álvarez-Lao, D. J., García-González, R., Rodríguez, L., Pérez-González, A., & Arsuaga, J. L. (2026). Towards a formation model of the Neanderthal symbolic accumulation of herbivore crania: Spatial patterns shaped by rockfall dynamics in Level 3 of Des-Cubierta Cave (Lozoya valley, Madrid, Spain). Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-025-02382-5

Neanderthal quiz: How much do you know about our closest relatives?

Sophie BerdugoSocial Links NavigationStaff writer

Sophie BerdugoSocial Links NavigationStaff writerSophie is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She covers a wide range of topics, having previously reported on research spanning from bonobo communication to the first water in the universe. Her work has also appeared in outlets including New Scientist, The Observer and BBC Wildlife, and she was shortlisted for the Association of British Science Writers' 2025 "Newcomer of the Year" award for her freelance work at New Scientist. Before becoming a science journalist, she completed a doctorate in evolutionary anthropology from the University of Oxford, where she spent four years looking at why some chimps are better at using tools than others.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more 'The images could be much older': Analysis of rocks shows Neanderthals made art at least 64,000 years ago

'The images could be much older': Analysis of rocks shows Neanderthals made art at least 64,000 years ago

Neanderthals cannibalized 'outsider' women and children 45,000 years ago at cave in Belgium

Neanderthals cannibalized 'outsider' women and children 45,000 years ago at cave in Belgium

'Perfectly preserved' Neanderthal skull bones suggest their noses didn't evolve to warm air

'Perfectly preserved' Neanderthal skull bones suggest their noses didn't evolve to warm air

10 things we learned about Neanderthals in 2025

10 things we learned about Neanderthals in 2025

18,000 years ago, ice age humans built dwellings out of mammoth bones in Ukraine

18,000 years ago, ice age humans built dwellings out of mammoth bones in Ukraine

'It is the most exciting discovery in my 40-year career': Archaeologists uncover evidence that Neanderthals made fire 400,000 years ago in England

Latest in Human Evolution

'It is the most exciting discovery in my 40-year career': Archaeologists uncover evidence that Neanderthals made fire 400,000 years ago in England

Latest in Human Evolution

430,000-year-old wooden handheld tools from Greece are the oldest on record — and they predate modern humans

430,000-year-old wooden handheld tools from Greece are the oldest on record — and they predate modern humans

160,000-year-old sophisticated stone tools discovered in China may not have been made by Homo sapiens

160,000-year-old sophisticated stone tools discovered in China may not have been made by Homo sapiens

2.6 million-year-old jaw from extinct 'Nutcracker Man' is found where we didn't expect it

2.6 million-year-old jaw from extinct 'Nutcracker Man' is found where we didn't expect it

Most complete Homo habilis skeleton ever found dates to more than 2 million years ago and retains 'Lucy'-like features

Most complete Homo habilis skeleton ever found dates to more than 2 million years ago and retains 'Lucy'-like features

Human origins quiz: How well do you know the story of humanity?

Human origins quiz: How well do you know the story of humanity?

Homo erectus wasn't the first human species to leave Africa 1.8 million years ago, fossils suggest

Latest in News

Homo erectus wasn't the first human species to leave Africa 1.8 million years ago, fossils suggest

Latest in News

More than 43,000 years ago, Neanderthals spent centuries collecting animal skulls in a cave; but archaeologists aren't sure why

More than 43,000 years ago, Neanderthals spent centuries collecting animal skulls in a cave; but archaeologists aren't sure why

Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.

Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.

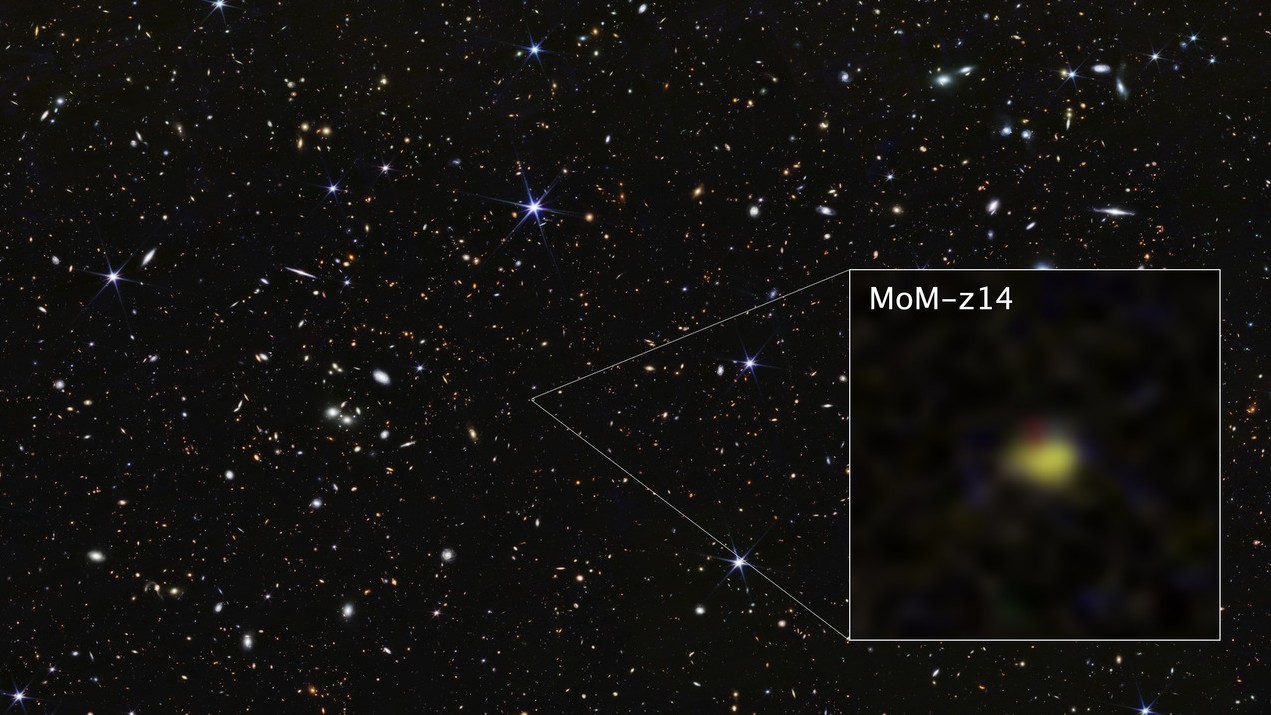

James Webb telescope breaks own record, discovering farthest known galaxy in the universe

James Webb telescope breaks own record, discovering farthest known galaxy in the universe

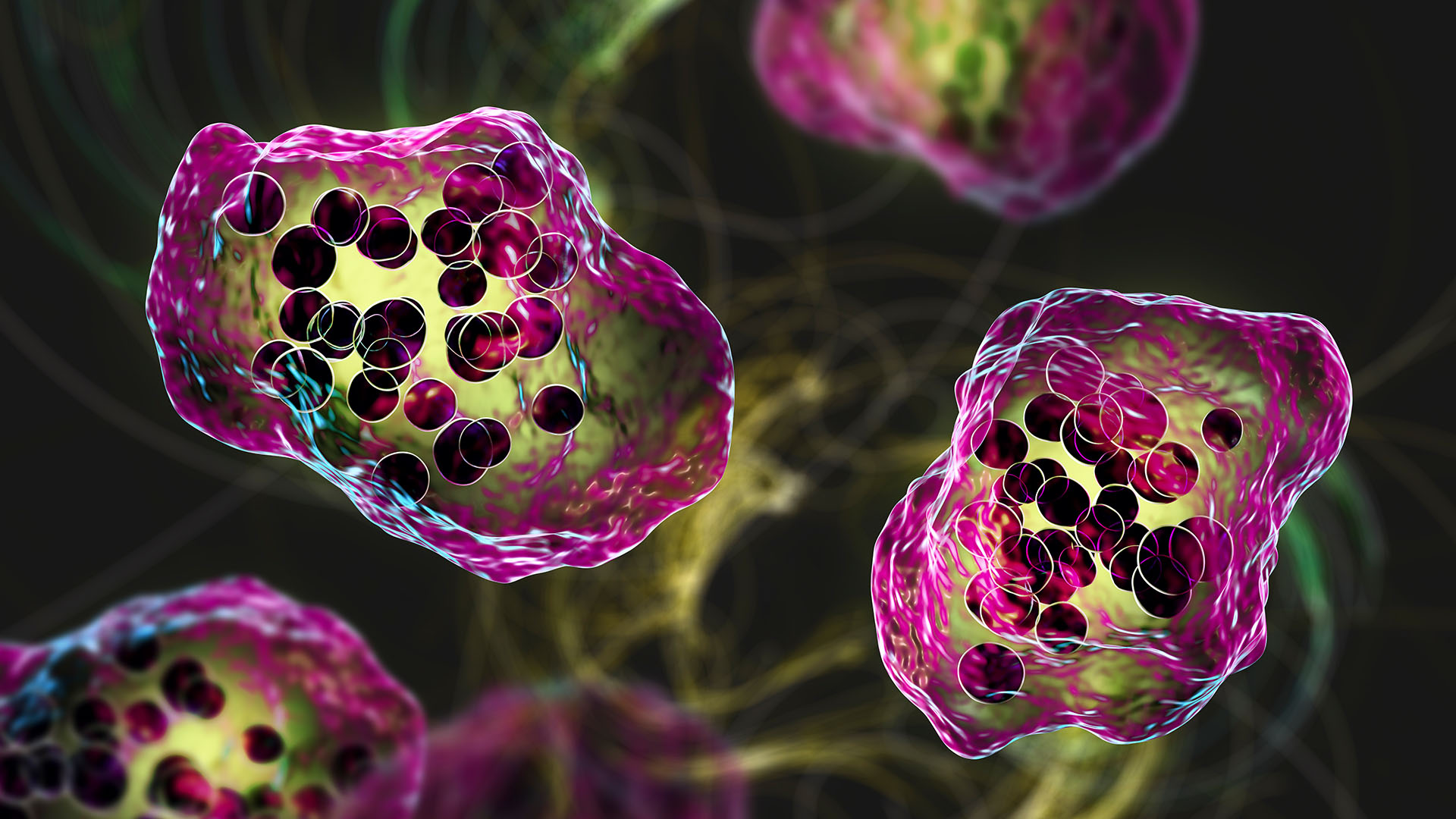

South Carolina's measles outbreak nears 790 cases — making it the biggest in decades

South Carolina's measles outbreak nears 790 cases — making it the biggest in decades

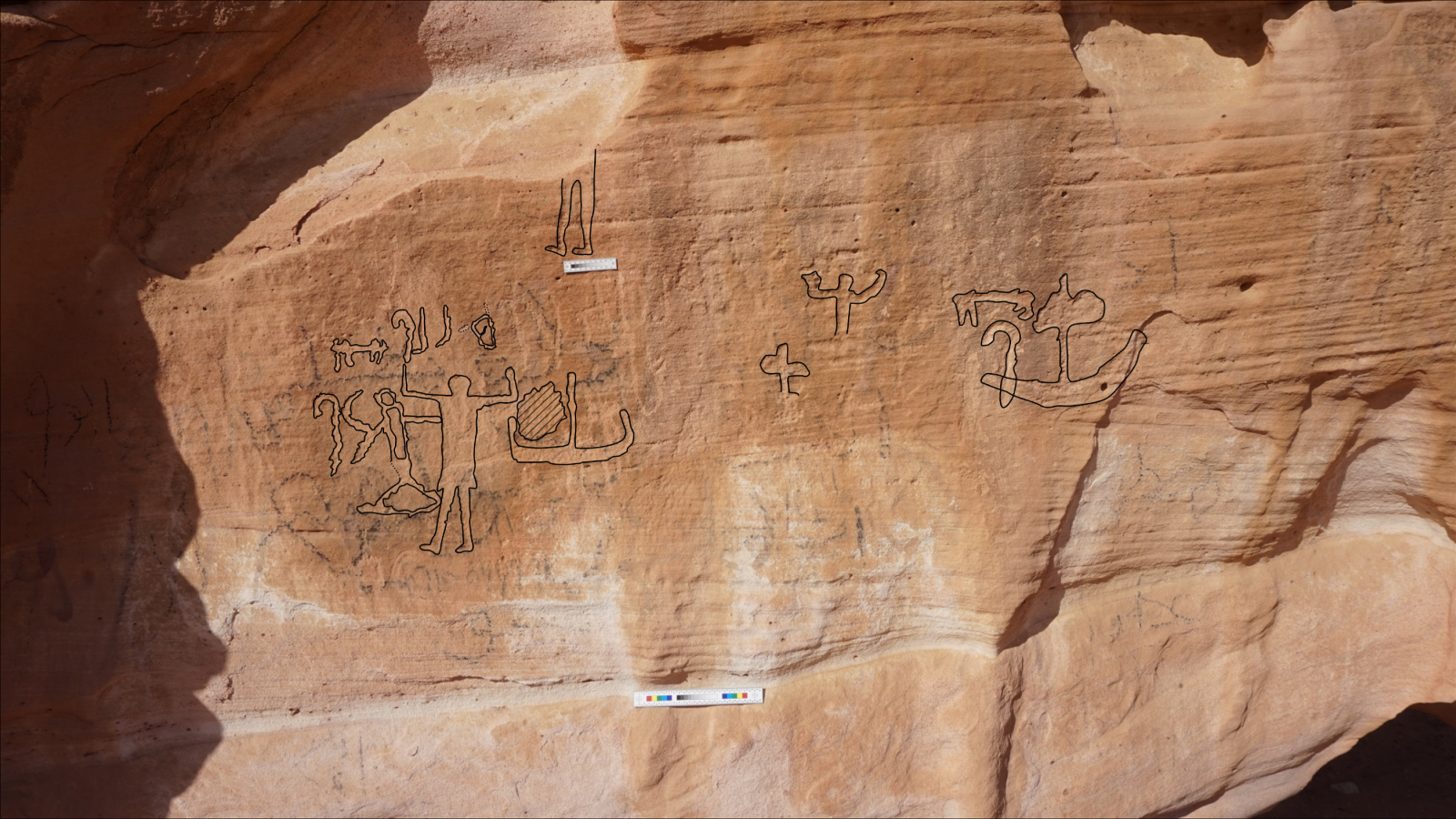

5,000-year-old rock art from ancient Egypt depicts 'terrifying' conquest of the Sinai Peninsula

5,000-year-old rock art from ancient Egypt depicts 'terrifying' conquest of the Sinai Peninsula

Stone Age teenager was mauled by a bear 28,000 years ago, skeletal analysis confirms

LATEST ARTICLES

Stone Age teenager was mauled by a bear 28,000 years ago, skeletal analysis confirms

LATEST ARTICLES 1Watch awkward Chinese humanoid robot lay it all down on the dance floor

1Watch awkward Chinese humanoid robot lay it all down on the dance floor- 2Hawke Frontier ED X 8x42 review

- 3The Snow Moon will 'swallow' one of the brightest stars in the sky this weekend: Where and when to look

- 4Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.

- 5James Webb telescope breaks own record, discovering farthest known galaxy in the universe