- Health

- Viruses, Infections & Disease

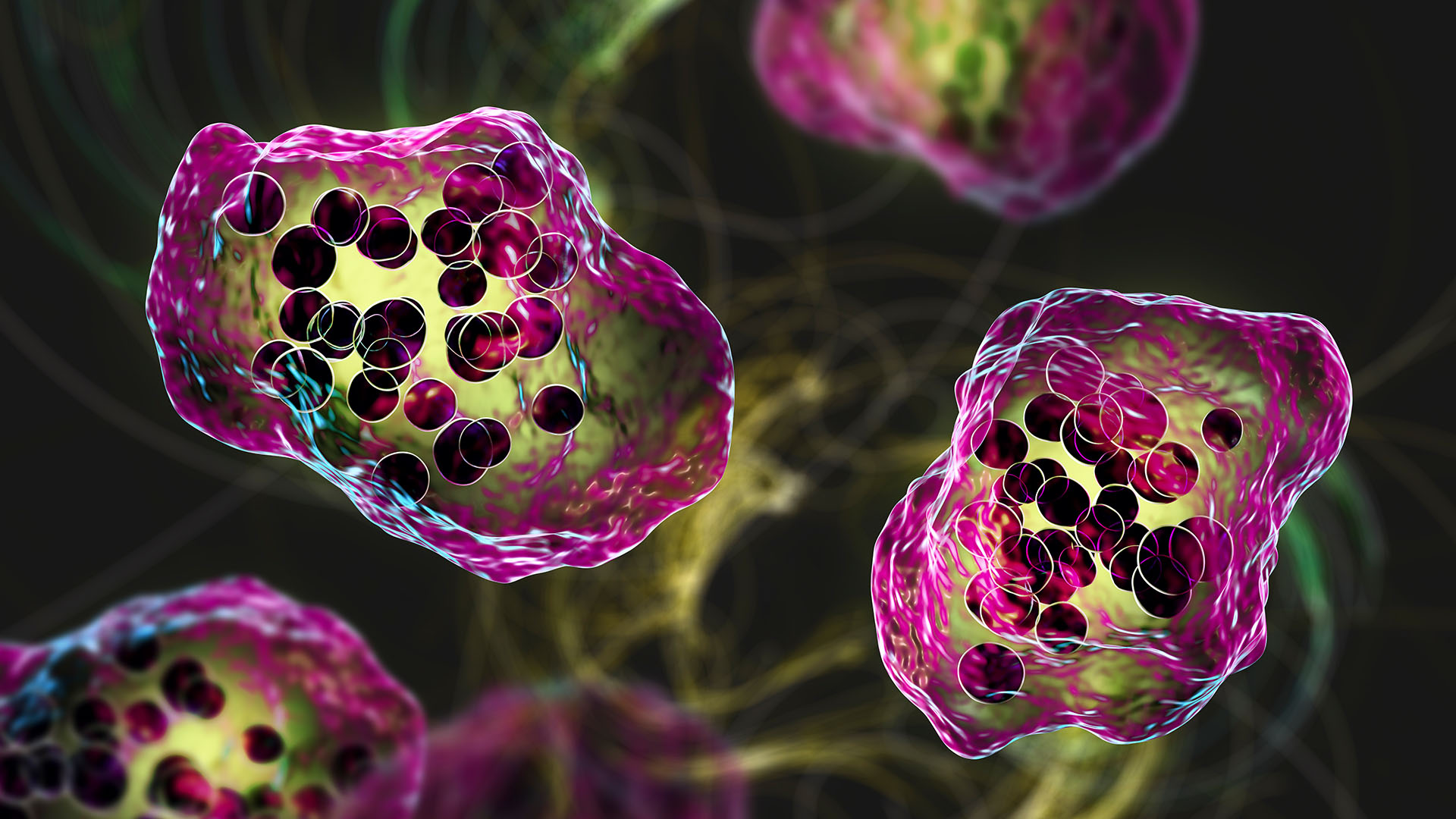

Using a laboratory model of the human nose, scientists have investigated why the severity of common-cold infections varies so widely between individuals.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

A local immune reaction inside the nose is key for fighting off colds, a study finds.

(Image credit: Getty)

Share

Share by:

A local immune reaction inside the nose is key for fighting off colds, a study finds.

(Image credit: Getty)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

New laboratory experiments used "noses-in-a-dish" to unpack why the common cold triggers mild illness in some people while sending others to the hospital.

In the depths of cold and flu season, rhinoviruses — the most common cause of the common cold — make many of us miserable, causing symptoms like a runny nose, sore throat and mild cough. But for a subset of people, rhinovirus infections are a much more serious condition.

You may like-

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

-

Insomnia and anxiety come with a weaker immune system — a new study starts to unravel why

Insomnia and anxiety come with a weaker immune system — a new study starts to unravel why

-

Aging and inflammation may not go hand in hand, study suggests

Aging and inflammation may not go hand in hand, study suggests

Now, a new study published Jan. 19 in the journal Cell Press Blue has demonstrated that this variation depends on the activation of distinct immune programs inside the infected nasal tissue. The team grew miniature models of the human nasal passages in dishes to study how cells react to infection.

They say their findings are a step toward developing effective antivirals against the common cold.

How to grow a nose in a dish

The cells that bear the brunt of common cold infections are the epithelial cells lining the nose. When these cells detect a viral infection, they signal to the innate immune system — the body's first, nonspecific line of defense against germs. Some of the first defenders that this system deploys are molecules called interferons.

Despite knowing that interferons play an important role in fighting viruses, researchers have found it difficult to understand exactly how they do so at the cellular level.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.The new research, led by Dr. Ellen Foxman, an associate professor of laboratory medicine and immunobiology at Yale University, used a technique called single-cell RNA sequencing, which reveals what information is being sent from a cell's control center that houses its DNA. They performed the analysis at the resolution of individual nasal epithelial cells.

Foxman's team grew these cells in a dish environment that closely resembled the inside of the human nose. Then, they infected the cells with a rhinovirus.

This pair of techniques enabled Foxman's team to gain new insight into how rhinoviruses affect nasal cells, said Clare Lloyd, a respiratory immunologist at Imperial College London who wasn't involved in the study.

You may like-

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

-

Insomnia and anxiety come with a weaker immune system — a new study starts to unravel why

Insomnia and anxiety come with a weaker immune system — a new study starts to unravel why

-

Aging and inflammation may not go hand in hand, study suggests

Aging and inflammation may not go hand in hand, study suggests

"I think it's a combination of having a multicellular organoid [the nose-in-a-dish], as well as having these much more sensitive and specific techniques to allow us to be able to look at how ciliated cells are affected and how mucus-producing cells are affected," Lloyd told Live Science. Ciliated cells — which have tiny, hairlike projections — and mucus-producing cells are both found in the lining of the nose.

Foxman's initial observation was that, even when separated from the rest of the body, the nose cells were quite adept at fighting rhinoviruses.

"During an optimal response, viruses infect only ~1% of the cells, and the infection starts resolving within a few days," Foxman said in a statement. But when the team exposed the cells to a drug that suppressed interferon signaling, the cells' previously stout defenses began to crumble.

In these latter conditions, more than 30% of the cells became infected and the immune response became more pronounced. Levels of pro-inflammatory molecules, including cytokines, shot up, and there was a significant increase in mucus-protein production.

In the interferons' absence, one protein appeared to be the chief conductor of this overactive response: nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB). The off-the-rails response resembled the reaction that often leads to complications of severe rhinovirus infection in vulnerable patients.

Lloyd said if a person is knocked flat by a rhinovirus infection, it may indicate issues with their interferon production. "Some people have genetic defects in interferon production … which may affect the tone of the interferon response they can generate," she said.

Lab studies like this are essential steps toward treating common viral infections, but Lloyd cautioned that antivirals targeting the immune response would have to manage a careful balancing act.

"The immune system is very nuanced," Lloyd said. "If you just completely block NF-κB, then you're blocking all kinds of cytokines and chemokines, so you're blocking the whole inflammatory response." Although inflammation can be harmful when it rages out of control, you do need some to combat infections effectively.

RELATED STORIES—Why are you more likely to catch a cold in winter?

—Why is it hard to hear when you have a cold?

—What's the difference between a cold and the flu?

Foxman's group tested some antivirals on their cell models, including an experimental drug called rupintrivir. This drug was particularly effective at suppressing an overactive immune response, at least in the lab models. Rupintrivir had previously failed to suppress rhinovirus infections in clinical trials with patients. But still, the study authors suggested the drug might have a second life as a treatment to subdue overactive immune responses to viruses in vulnerable groups, such as patients with COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease).

Mehul Suthar, a professor at Emory Vaccine Center who was not involved with the study, said drugs targeting the virus itself would be more precise than drugs that target an orchestrator of the immune response. Rupintrivir, for instance, targets viral proteins.

Rhinoviruses have remained a persistent pest for humanity because they can quickly evolve in response to treatments, thereby gaining resistance against them. It's only through a precise understanding of why colds make us ill that we can find a solution.

"It's obviously very challenging," Suthar said. "Otherwise, we'd have drugs for every virus out there."

Article SourcesWang, B., Amat, J. A., Mihaylova, V. T., Kong, Y., Wang, G., & Foxman, E. F. (2026). Rhinovirus triggers distinct host responses through differential engagement of epithelial innate immune signaling. Cell Press Blue, 100001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpblue.2025.100001

RJ MackenzieLive Science Contributor

RJ MackenzieLive Science ContributorRJ Mackenzie is an award-nominated science and health journalist. He has degrees in neuroscience from the University of Edinburgh and the University of Cambridge. He became a writer after deciding that the best way of contributing to science would be from behind a keyboard rather than a lab bench. He has reported on everything from brain-interface technology to shape-shifting materials science, and from the rise of predatory conferencing to the importance of newborn-screening programs. He is a former staff writer of Technology Networks.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

Insomnia and anxiety come with a weaker immune system — a new study starts to unravel why

Insomnia and anxiety come with a weaker immune system — a new study starts to unravel why

Aging and inflammation may not go hand in hand, study suggests

Aging and inflammation may not go hand in hand, study suggests

Heart attacks are less harmful at night. And that might be key to treating them.

Heart attacks are less harmful at night. And that might be key to treating them.

'Perfectly preserved' Neanderthal skull bones suggest their noses didn't evolve to warm air

'Perfectly preserved' Neanderthal skull bones suggest their noses didn't evolve to warm air

Viruses that evolved on the space station and were sent back to Earth were more effective at killing bacteria

Latest in Viruses, Infections & Disease

Viruses that evolved on the space station and were sent back to Earth were more effective at killing bacteria

Latest in Viruses, Infections & Disease

New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds

New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds

South Carolina's measles outbreak nears 790 cases — making it the biggest in decades

South Carolina's measles outbreak nears 790 cases — making it the biggest in decades

The UK has lost its measles elimination status — again

The UK has lost its measles elimination status — again

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

Why is flu season so bad this year?

Why is flu season so bad this year?

Viruses that evolved on the space station and were sent back to Earth were more effective at killing bacteria

Latest in News

Viruses that evolved on the space station and were sent back to Earth were more effective at killing bacteria

Latest in News

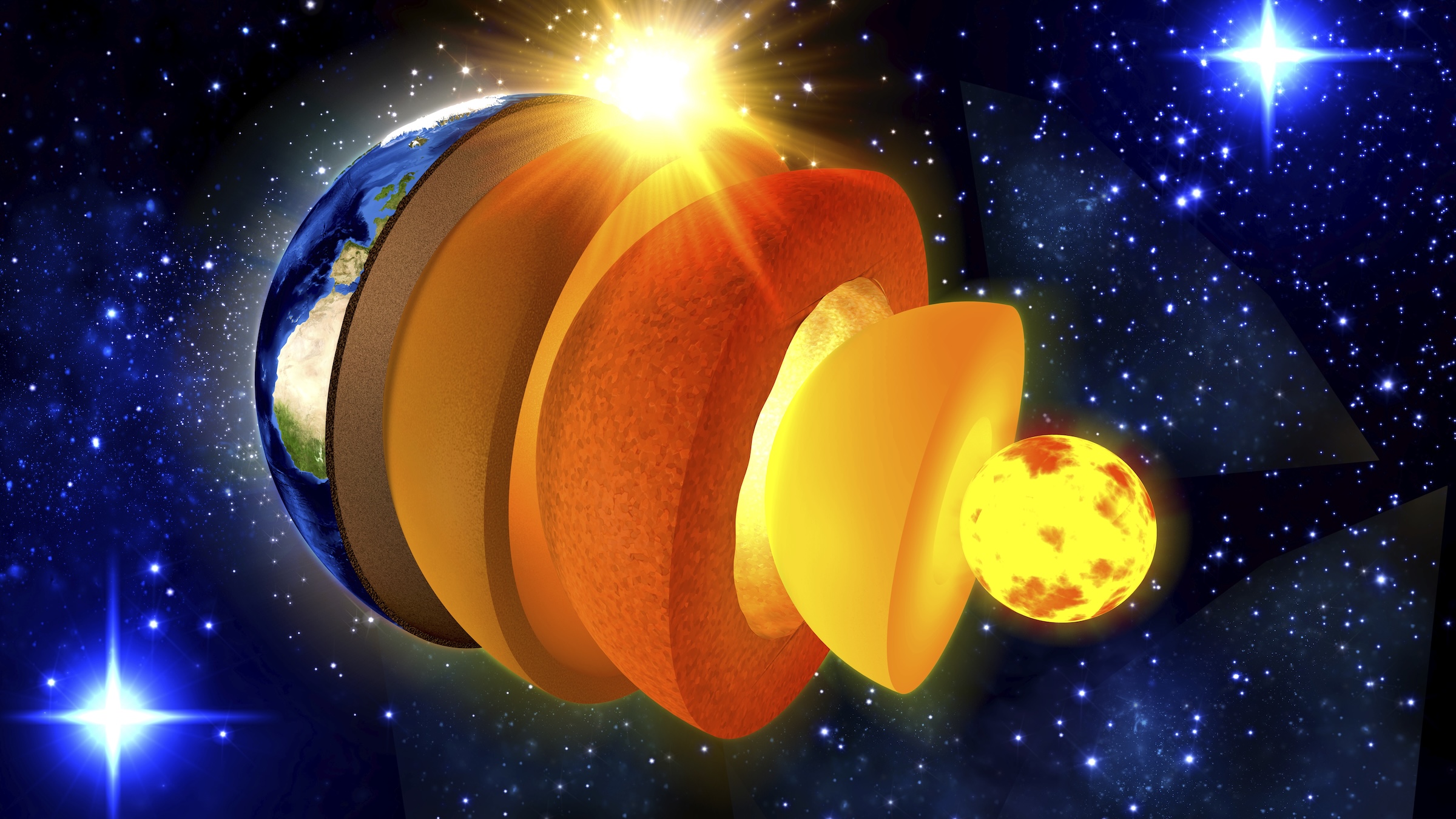

Earth is 'missing' lighter elements. They may be hiding in its solid inner core.

Earth is 'missing' lighter elements. They may be hiding in its solid inner core.

Lifespan may be 50% heritable, study suggests

Lifespan may be 50% heritable, study suggests

Astronomers spot 'time-warped' supernovas whose light both has and hasn't reached Earth

Astronomers spot 'time-warped' supernovas whose light both has and hasn't reached Earth

Life may have rebounded 'ridiculously fast' after the dinosaur-killing asteroid impact

Life may have rebounded 'ridiculously fast' after the dinosaur-killing asteroid impact

'Nose-in-a-dish' reveals why the common cold hits some people hard, while others recover easily

'Nose-in-a-dish' reveals why the common cold hits some people hard, while others recover easily

Rare medieval seal discovered in UK is inscribed with 'Richard's secret' and bears a Roman-period gemstone

LATEST ARTICLES

Rare medieval seal discovered in UK is inscribed with 'Richard's secret' and bears a Roman-period gemstone

LATEST ARTICLES 1Earth is 'missing' lighter elements. They may be hiding in its solid inner core.

1Earth is 'missing' lighter elements. They may be hiding in its solid inner core.- 2Rare medieval seal discovered in UK is inscribed with 'Richard's secret' and bears a Roman-period gemstone

- 3Oneisall Pet Air Purifier (PP02) review: Great value pick for dog and cat lovers

- 4Stellar nursery bursts with newborn stars in hauntingly beautiful Hubble telescope image — Space photo of the week

- 5When were boats invented?