- Archaeology

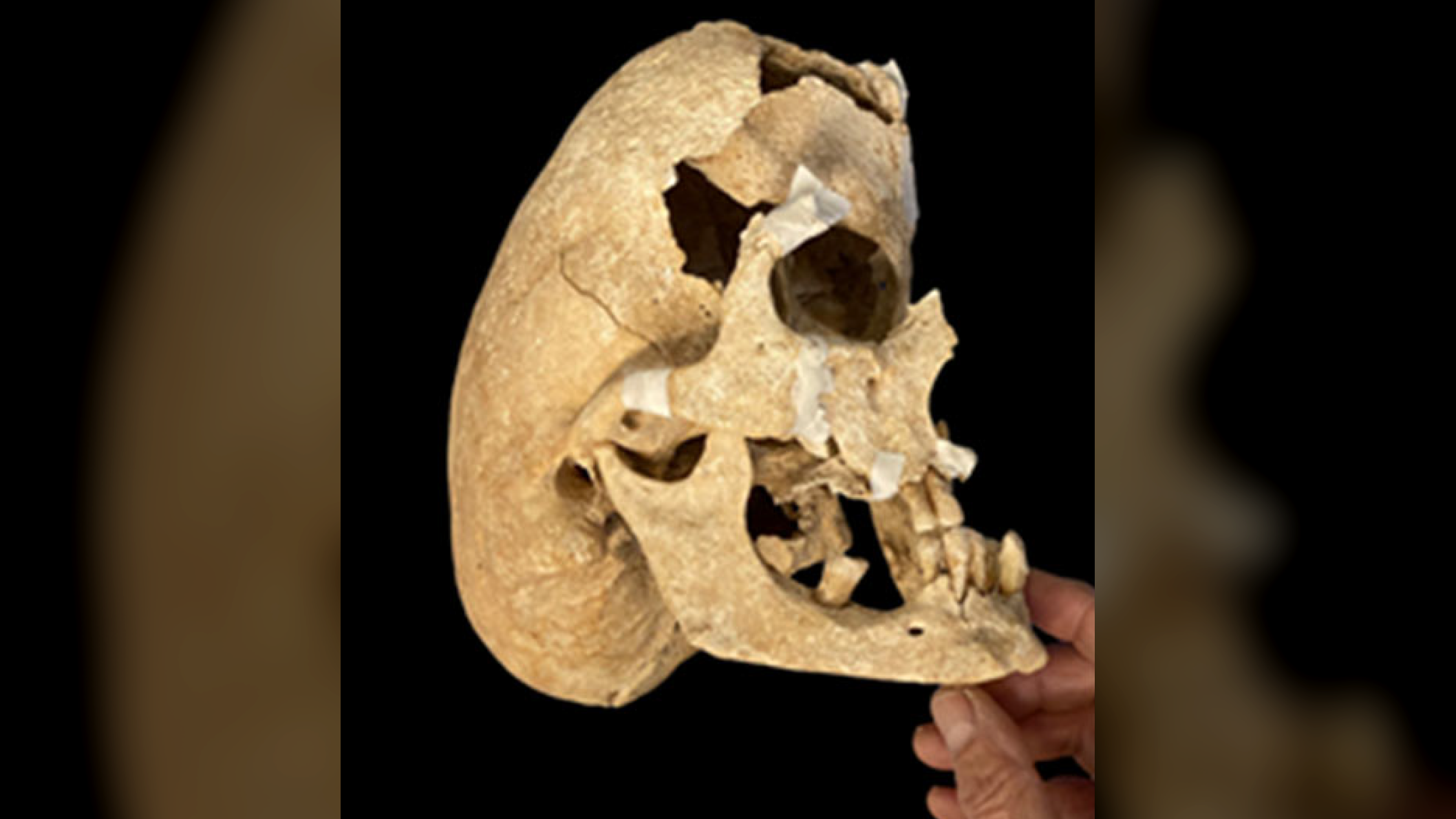

In 1963, researchers unearthed two Stone Age skeletons that were buried in an embraced position in a cave in Italy. Now, DNA testing has revealed that one of them had a rare genetic condition.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

Researchers have identified a rare form of dwarfism in a Stone Age skeleton.

(Image credit: Adrian Daly)

Share by:

Researchers have identified a rare form of dwarfism in a Stone Age skeleton.

(Image credit: Adrian Daly)

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

A Stone Age person buried 12,000 years ago in a cave in Italy had a rare genetic disorder that shortened her arms and legs, a new study finds.

A DNA analysis of her skeleton revealed that she was a teenage girl who had a rare form of dwarfism. The finding is the earliest DNA diagnosis of a genetic disease in an anatomically modern human, the researchers said.

"As this is the earliest DNA confirmed genetic diagnosis ever made in humans, the earliest diagnosis of a rare disease, and the earliest familial genetic case, it is a real breakthrough for medical science," study co-author Adrian Daly, a physician and researcher in endocrinology at the University Hospital of Liège in Belgium, told Live Science in an email. "Identifying with near certainty a single base change in a gene in a person that died between 12,000 and 13,000 years ago is the earliest such diagnosis by about 10 millennia."

You may like-

Oldest known evidence of father-daughter incest found in 3,700-year-old bones in Italy

Oldest known evidence of father-daughter incest found in 3,700-year-old bones in Italy

-

Stone Age teenager was mauled by a bear 28,000 years ago, skeletal analysis confirms

Stone Age teenager was mauled by a bear 28,000 years ago, skeletal analysis confirms

-

5,500-year-old human skeleton discovered in Colombia holds the oldest evidence yet that syphilis came from the Americas

5,500-year-old human skeleton discovered in Colombia holds the oldest evidence yet that syphilis came from the Americas

Researchers found that the teenager — nicknamed "Romito 2," after the cave where her remains and those of eight other prehistoric hunter-gatherers were discovered in 1963 — had a rare genetic disorder called acromesomelic dysplasia, Maroteaux type (AMDM). This condition results in an extreme shortening of the limbs, particularly the forearms, forelegs, hands and feet.

AMDM is caused by mutations on both chromosomes of the NPR2 gene, which plays a key role in bone growth. As a result of her condition, Romito 2 "would have faced challenges in displacement over distances and terrain, while movement limitations at the elbow and hands would have affected her daily activities," Daly and his colleagues wrote in the study, which was published Wednesday (Jan. 28) in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Romito 2 was around 3 feet, 7 inches (110 centimeters) tall. Contrary to previous research that proposed the skeleton was male, DNA testing using material collected from the left inner ear revealed Romito 2 was female. She was buried in an embraced position with an adult nicknamed "Romito 1," who was also interred in the limestone Romito Cave in southern Italy.

DNA testing also showed that Romito 1 was female and a first-degree relative of Romito 2, meaning they were mother and daughter, or potentially sisters. Intriguingly, Romito 1 was shorter than average for adults at the time, measuring 4 feet, 9 inches (145 cm) tall.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.The analysis revealed that Romito 1 carried one abnormal copy of the NPR2 gene, which may have limited her growth somewhat — but not to the same extent as Romito 2, who carried two abnormal copies of the gene and, therefore, showed more pronounced dwarfism.

RELATED STORIES—European hunter-gatherers boated to North Africa during Stone Age, ancient DNA suggests

—Stone Age family may have been cannibalized for 'ultimate elimination' 5,600 years ago, study suggests

—See 'hyperrealistic' reconstructions of 2 Stone Age sisters who worked in brutal mine in the Czech Republic 6,000 years ago

Genetic material from the skeletons confirmed that Romito 1 and Romito 2 were from the Villabruna genetic cluster, a population of hunter-gatherers that expanded from Southern Europe into Central and Western Europe roughly 14,000 years ago. The researchers did not find evidence of close inbreeding, but the population that lived near Romito Cave was probably small, according to the study.

It's still unclear how Romito 1 and Romito 2 died, as their remains show no signs of trauma. Romito 2's diet and nutritional condition were similar to those of the other people buried in Romito Cave, suggesting that her community looked after her.

"The challenges she faced were met by the provision of care in her family group," the researchers wrote in the study.

Article SourcesFernandes, D. M., Llanos-Lizcano, A., Brück, F., Oberreiter, V., Özdoğan, K. T., Cheronet, O., Lucci, M., Beckers, A., Pétrossians, P., Coppa, A., Pinhasi, R. & Daly, A. F. (2026). A 12,000-year-old case of NPR2-related acromesomelic dysplasia. The New England Journal of Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2513616

Sascha PareSocial Links NavigationStaff writer

Sascha PareSocial Links NavigationStaff writer Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

View MoreYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Oldest known evidence of father-daughter incest found in 3,700-year-old bones in Italy

Oldest known evidence of father-daughter incest found in 3,700-year-old bones in Italy

Stone Age teenager was mauled by a bear 28,000 years ago, skeletal analysis confirms

Stone Age teenager was mauled by a bear 28,000 years ago, skeletal analysis confirms

5,500-year-old human skeleton discovered in Colombia holds the oldest evidence yet that syphilis came from the Americas

5,500-year-old human skeleton discovered in Colombia holds the oldest evidence yet that syphilis came from the Americas

Ancient DNA reveals mysterious Indigenous lineage that lived in Argentina for nearly 8,500 years — but rarely interacted with others

Ancient DNA reveals mysterious Indigenous lineage that lived in Argentina for nearly 8,500 years — but rarely interacted with others

'An extreme end of human genetic variation': Ancient humans were isolated in southern Africa for nearly 100,000 years, and their genetics are stunningly different

'An extreme end of human genetic variation': Ancient humans were isolated in southern Africa for nearly 100,000 years, and their genetics are stunningly different

'I had never seen a skull like this before': Medieval Spanish knight who died in battle had a rare genetic condition, study finds

Latest in Archaeology

'I had never seen a skull like this before': Medieval Spanish knight who died in battle had a rare genetic condition, study finds

Latest in Archaeology

Rare medieval seal discovered in UK is inscribed with 'Richard's secret' and bears a Roman-period gemstone

Rare medieval seal discovered in UK is inscribed with 'Richard's secret' and bears a Roman-period gemstone

'It's similar to how Google can map your home without your consent': Why using aerial lasers to map an archaeology site should have Indigenous partnership

'It's similar to how Google can map your home without your consent': Why using aerial lasers to map an archaeology site should have Indigenous partnership

More than 43,000 years ago, Neanderthals spent centuries collecting animal skulls in a cave; but archaeologists aren't sure why

More than 43,000 years ago, Neanderthals spent centuries collecting animal skulls in a cave; but archaeologists aren't sure why

Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.

Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.

When were boats invented?

When were boats invented?

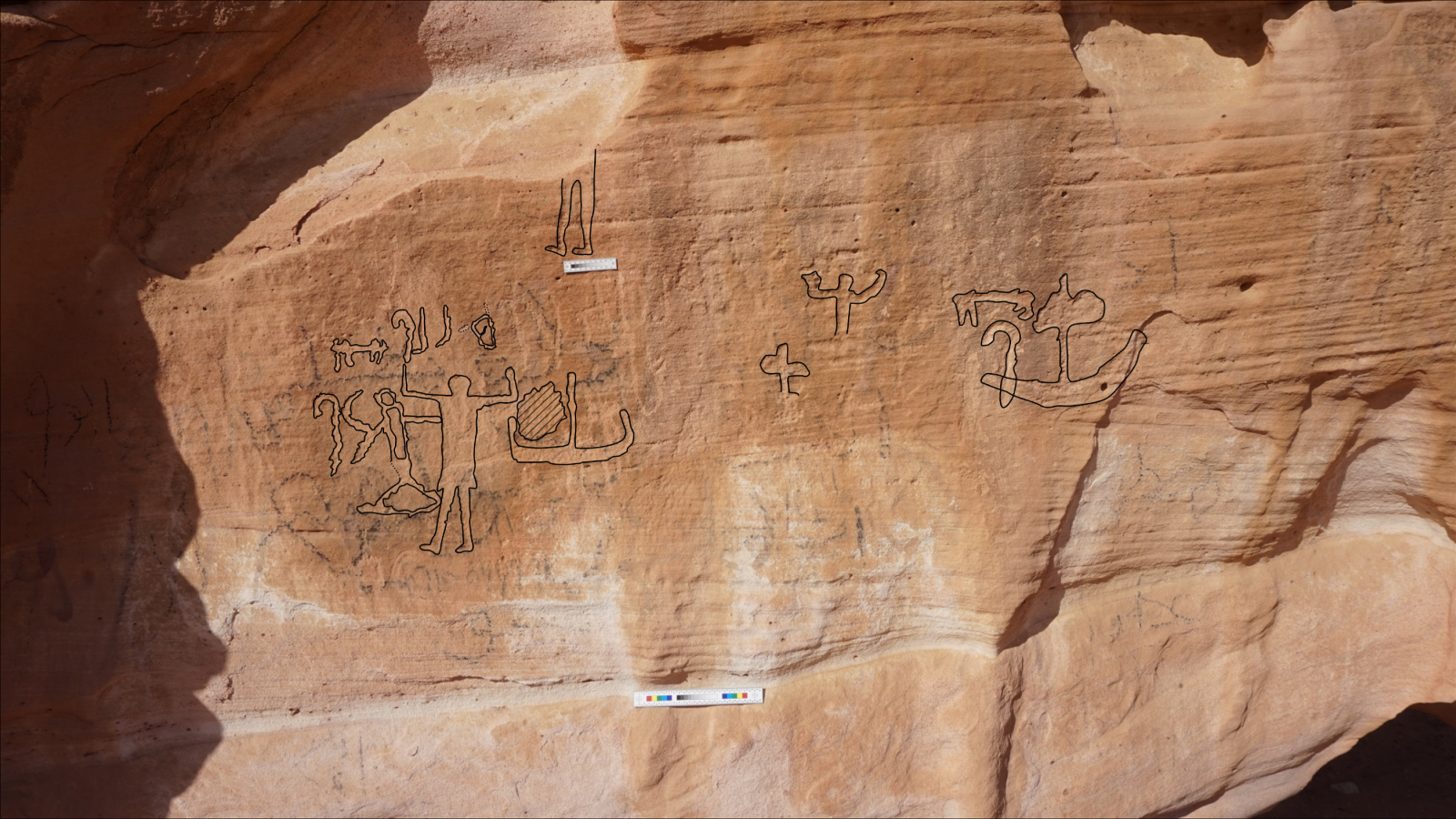

5,000-year-old rock art from ancient Egypt depicts 'terrifying' conquest of the Sinai Peninsula

Latest in News

5,000-year-old rock art from ancient Egypt depicts 'terrifying' conquest of the Sinai Peninsula

Latest in News

What is Moltbook? A social network for AI threatens a 'total purge' of humanity — but some experts say it's a hoax

What is Moltbook? A social network for AI threatens a 'total purge' of humanity — but some experts say it's a hoax

Enormous 'mega-blob' under Hawaii is solid rock and iron, not gooey — and it may fuel a hotspot

Enormous 'mega-blob' under Hawaii is solid rock and iron, not gooey — and it may fuel a hotspot

Artemis II simulated launch window opens tonight as NASA delays mission due to 'rare Arctic outbreak'

Artemis II simulated launch window opens tonight as NASA delays mission due to 'rare Arctic outbreak'

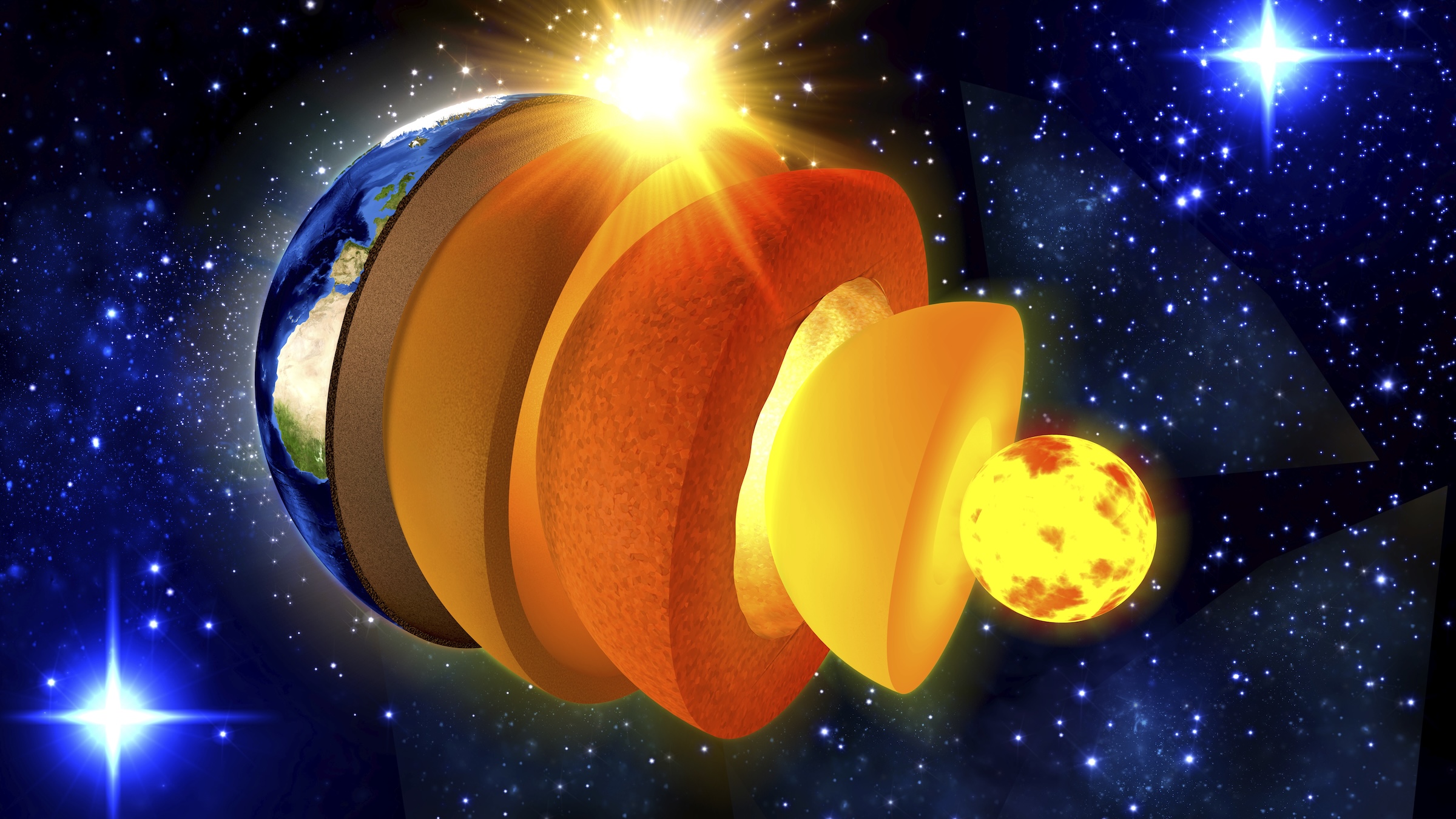

Earth is 'missing' lighter elements. They may be hiding in its solid inner core.

Earth is 'missing' lighter elements. They may be hiding in its solid inner core.

Lifespan may be 50% heritable, study suggests

Lifespan may be 50% heritable, study suggests

Astronomers spot 'time-warped' supernovas whose light both has and hasn't reached Earth

LATEST ARTICLES

Astronomers spot 'time-warped' supernovas whose light both has and hasn't reached Earth

LATEST ARTICLES 1What is Moltbook? A social network for AI threatens a 'total purge' of humanity — but some experts say it's a hoax

1What is Moltbook? A social network for AI threatens a 'total purge' of humanity — but some experts say it's a hoax- 2Enormous 'mega-blob' under Hawaii is solid rock and iron, not gooey — and it may fuel a hotspot

- 3Canon 15x50 IS All Weather binocular review

- 4The Colorado River's largest tributary flows 'uphill' for over 100 miles — and geologists may finally have an explanation for it

- 5Artemis II simulated launch window opens tonight as NASA delays mission due to 'rare Arctic outbreak'