- Space

- Astronomy

- Black Holes

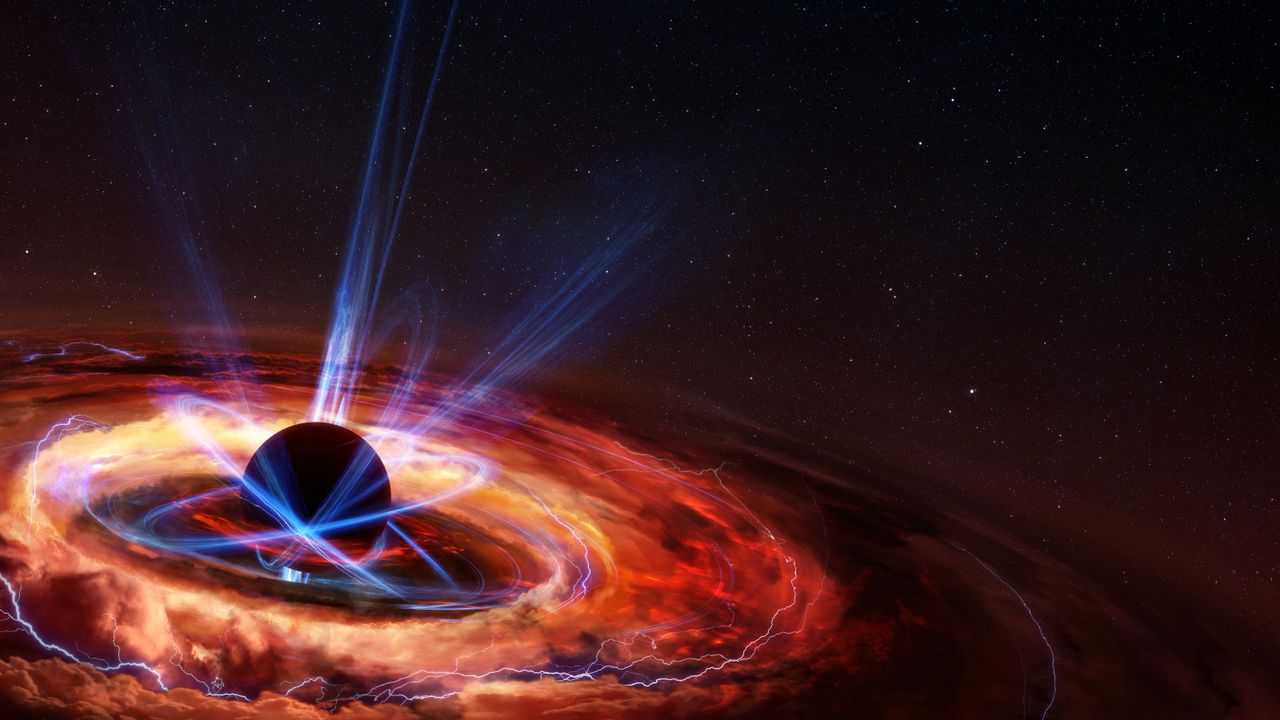

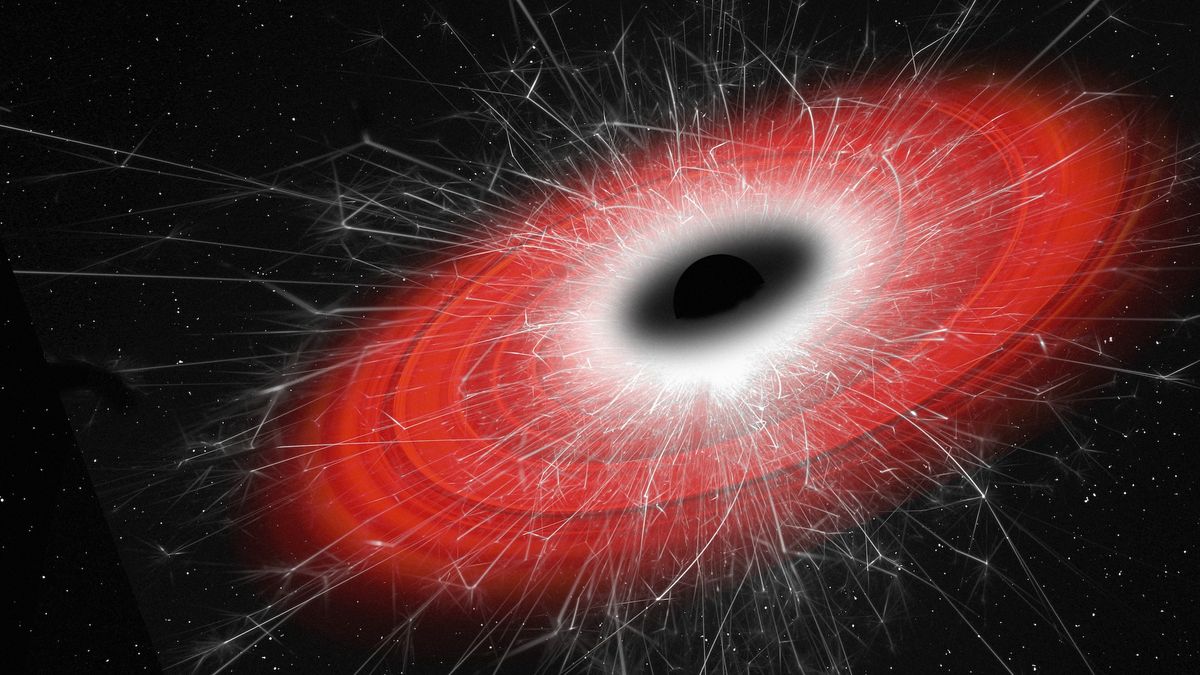

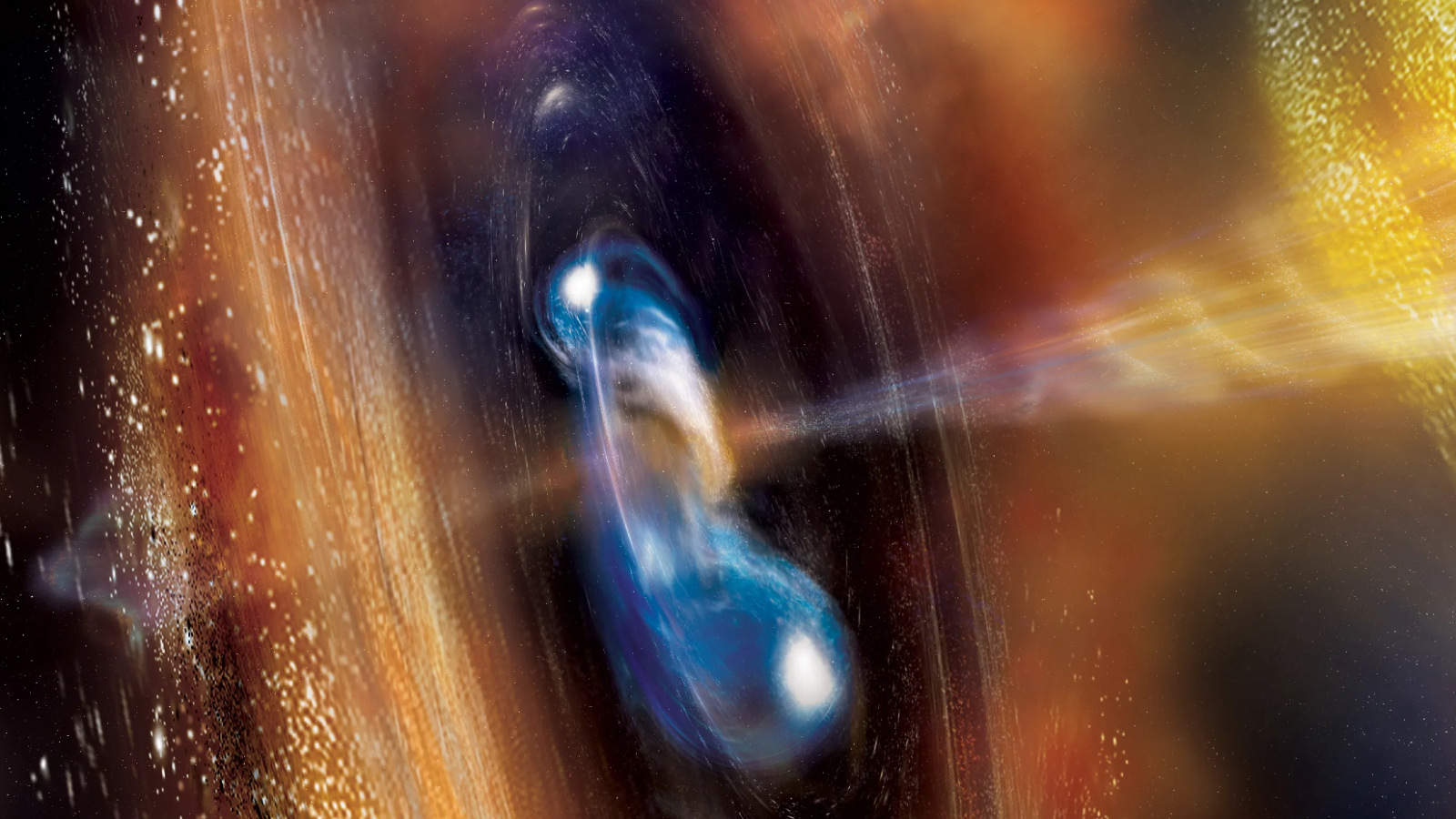

A supercharged neutrino that smashed into our planet in 2023 may have been spit out by an exploding primordial black hole with a "dark charge." If true, this theory could lead to a definitive catalog of all subatomic particles and unveil the elusive identity of dark matter.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

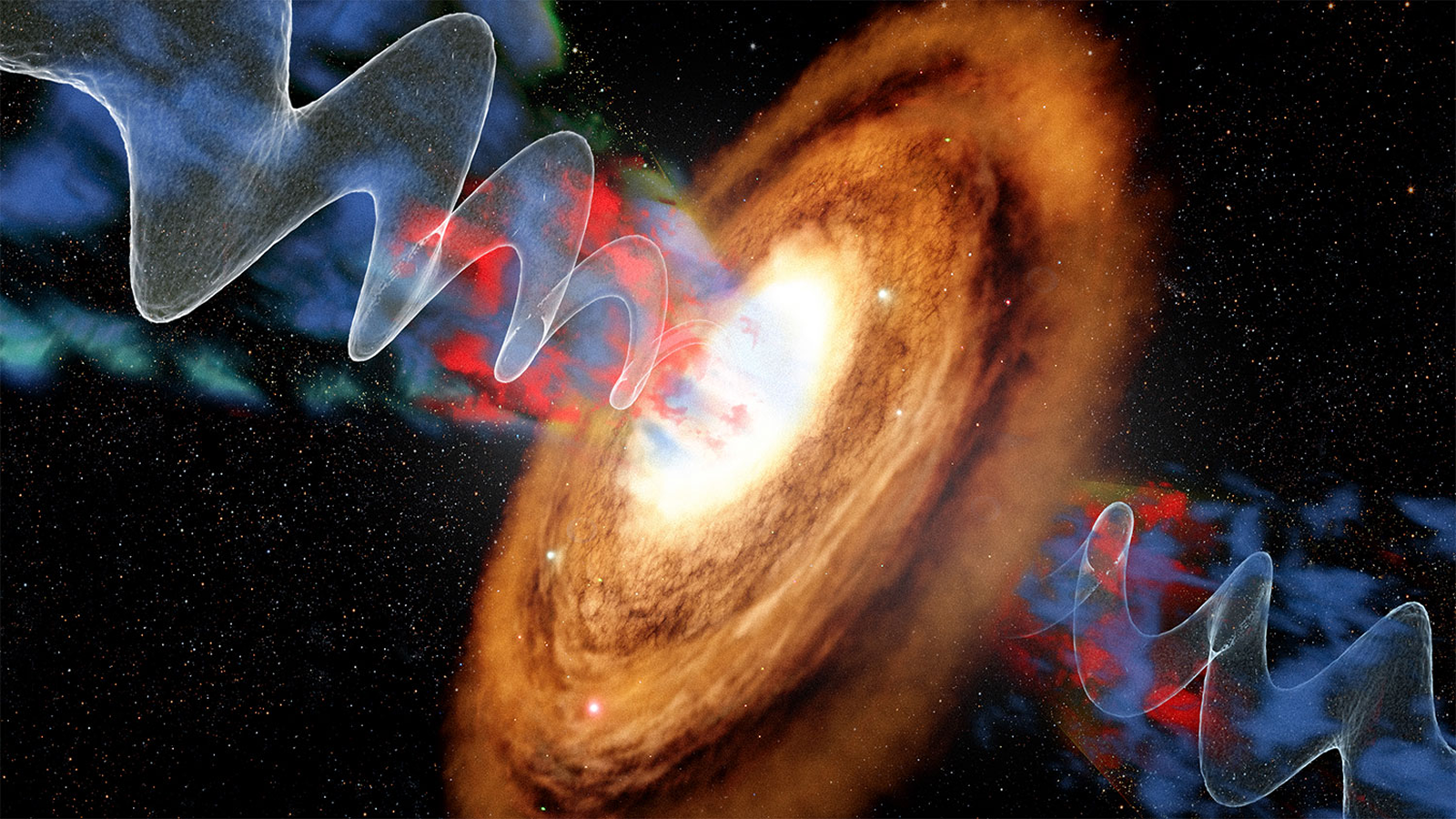

A new paper suggests that an impossibly energetic neutrino, that slammed into Earth in 2023, may have been unleashed by an exploding black hole.

(Image credit: Illustration by Tobias Roetsch for All About Space magazine/Future Publishing via Getty Images)

A new paper suggests that an impossibly energetic neutrino, that slammed into Earth in 2023, may have been unleashed by an exploding black hole.

(Image credit: Illustration by Tobias Roetsch for All About Space magazine/Future Publishing via Getty Images)

- Copy link

- X

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Become a Member in Seconds

Unlock instant access to exclusive member features.

Contact me with news and offers from other Future brands Receive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsors By submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Signup +

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Signup +

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Signup +

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Signup +

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Signup +

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Signup +Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Explore An account already exists for this email address, please log in. Subscribe to our newsletterAn impossibly powerful "ghost particle" that recently slammed into Earth may have come from a rare type of exploding black hole, researchers claim.

If true, the extraordinary event may prove a theory that could upend our understanding of both particle physics and dark matter, the team argues. However, this is just one theory, and there is no direct evidence to confirm that this is indeed what happened.

In early 2023, researchers at the Cubic Kilometre Neutrino Telescope (KM3NeT) — a massive, newly constructed array of sensors at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea — detected a neutrino, a ghostly particle that has almost no mass and does not readily interact with most matter.

You may like-

Dark matter and neutrinos may interact, hinting at 'fundamental breakthrough' in particle physics

Dark matter and neutrinos may interact, hinting at 'fundamental breakthrough' in particle physics

-

Record-breaking black hole collision finally explained

Record-breaking black hole collision finally explained

-

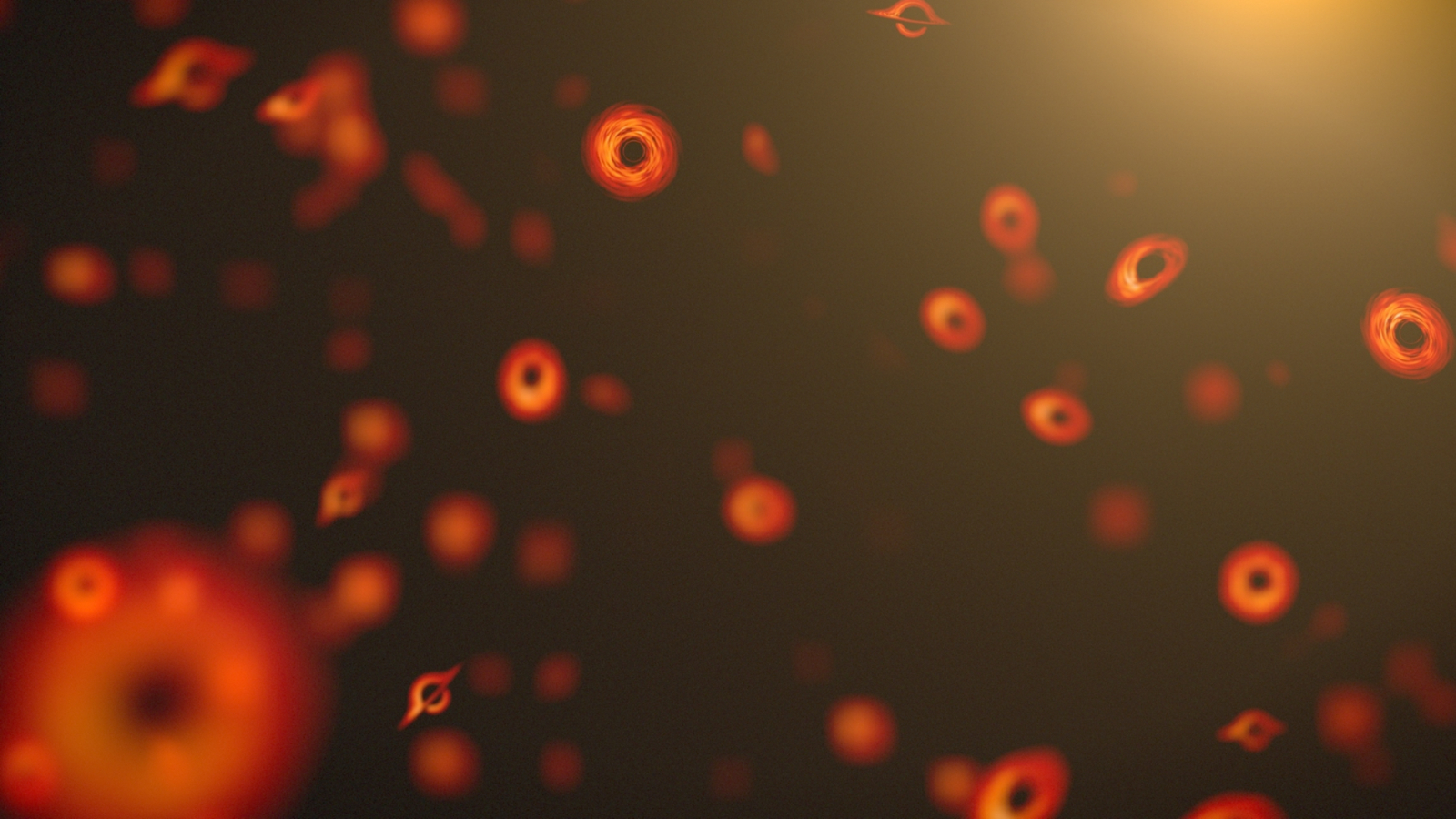

Some objects we thought were planets may actually be tiny black holes from the dawn of time

Some objects we thought were planets may actually be tiny black holes from the dawn of time

In addition to neutrinos' typical weirdness, this specific particle was noteworthy for its unusual intensity. It hit our planet with an estimated energy of up to 220 quadrillion electron volts, which is at least 100 times more powerful than any other neutrino detected to date and around 100,000 times greater than anything observed within human-made particle accelerators, like CERN's Large Hadron Collider.

Explaining the impossible

Researchers were initially unsure what caused this "impossible" neutrino to appear. It may have been birthed when a cosmic ray entered Earth's atmosphere, unleashing a cascade of high-energy particles that rained down on the planet's surface. However, its unprecedented power led experts to assume that it must have originated from some high-energy cosmic event that we don't fully understand.

In the new paper, which has been accepted for publication in the journal Physical Review Letters, one research group believes they have finally identified what really birthed the neutrino: an exploding, primordial black hole (PBH).

PBHs are a hypothetical class of black holes that are extremely small — potentially ranging from the size of an atom to a pinhead — and likely date back to the first moments after the Big Bang. The concept was first popularized by British physicist Stephen Hawking in the early 1970s, who also hinted that these miniature singularities would emit large quantities of high-energy particles, dubbed Hawking radiation, as they slowly evaporated. In theory, this would also mean they have the capacity to explode.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over."The lighter a black hole is, the hotter it should be and the more particles it will emit," study co-author Andrea Thamm, a theoretical physicist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, said in a statement. "As PBHs evaporate, they become ever lighter, and so hotter, emitting even more radiation in a runaway process until explosion."

One of the biggest mysteries surrounding the impossible neutrino, aside from its immense power, is that it was not observed by other neutrino detectors around the world, such as the IceCube Neutrino Observatory buried beneath Antarctica's icy surface. Given that PBHs are supposed to be fairly common throughout the universe, one would reasonably expect that similarly powerful particles also would have been detected before or since this possible discovery, especially as the number of neutrino detectors is quickly increasing.

The researchers said this is because the neutrino was emitted by a special type of PBH, dubbed a quasi-extremal PBH, which has a "dark charge" — a version of regular electric force that includes a very heavy, hypothesized version of the electron dubbed a "dark electron."

You may like-

Dark matter and neutrinos may interact, hinting at 'fundamental breakthrough' in particle physics

Dark matter and neutrinos may interact, hinting at 'fundamental breakthrough' in particle physics

-

Record-breaking black hole collision finally explained

Record-breaking black hole collision finally explained

-

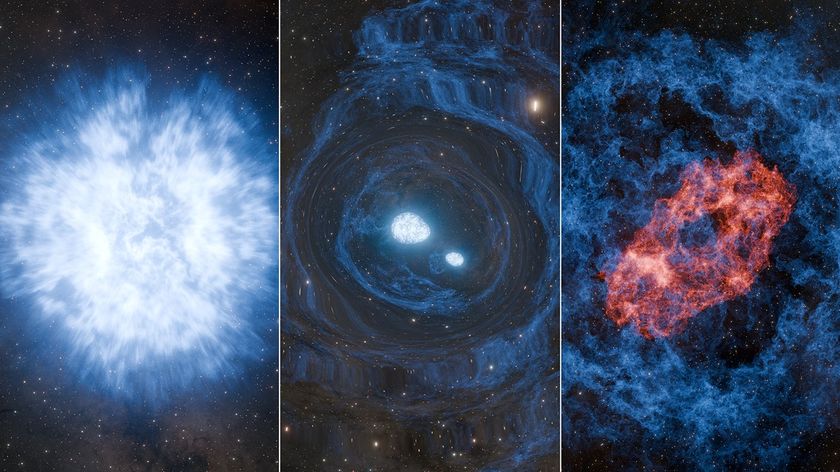

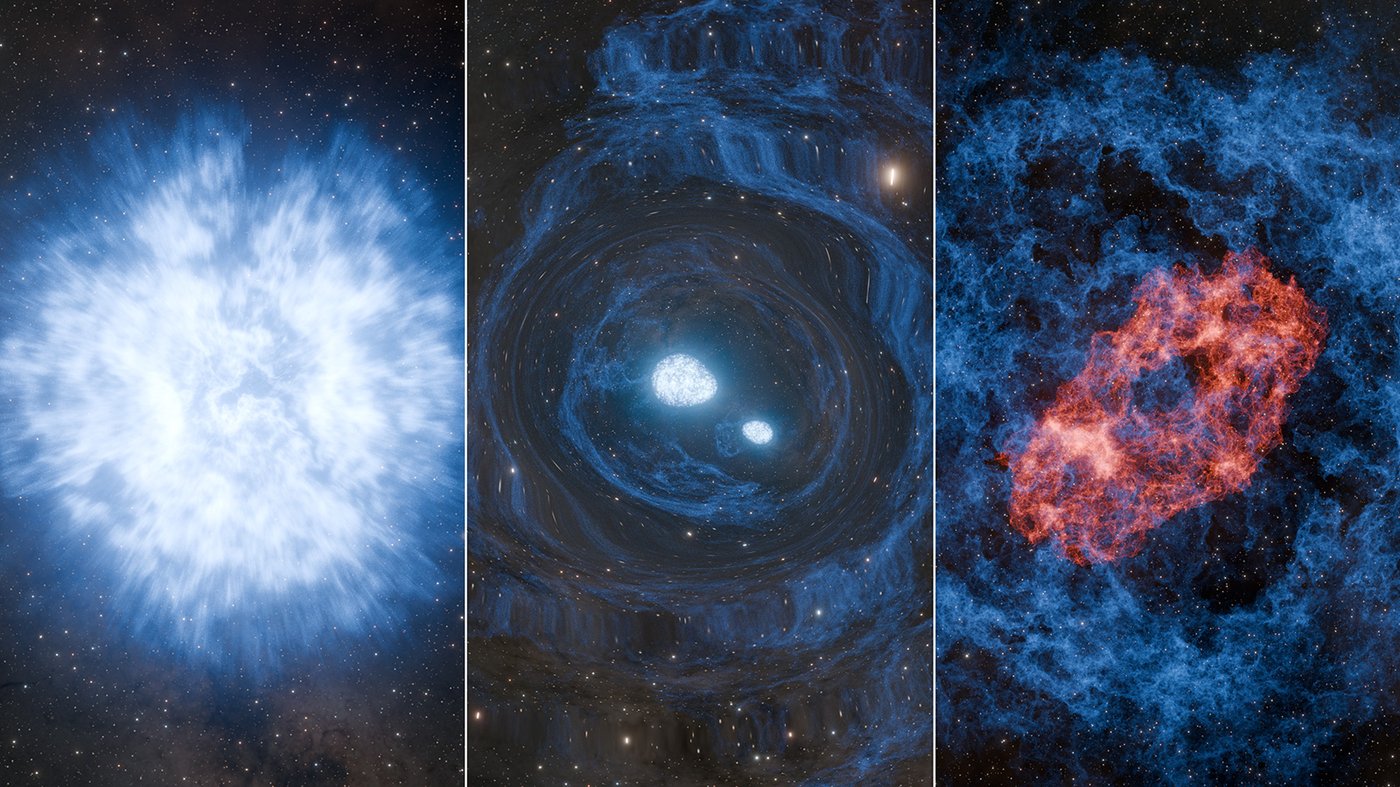

First-ever 'superkilonova' double star explosion puzzles astronomers

First-ever 'superkilonova' double star explosion puzzles astronomers

The dark properties of this theoretical type of PBH make it less likely that these black holes' explosions would be detected, the researchers suggested. It may also be that some of the less-powerful neutrinos detected to date may be partially incomplete detections of these events, they added.

"A PBH with a dark charge has unique properties and behaves in ways that are different from other, simpler PBH models," Thamm said. "We have shown that this can provide an explanation of all of the seemingly inconsistent experimental data."

Upending cosmic understanding

While the new research hints at the existence of quasi-extremal PBHs, it does not confirm them or prove that they explode as the researchers think. (Regular PBHs have never been directly observed, either, although there is a strong consensus that they exist.)

However, the team is confident that it will not take long to prove these dark explosions are real. The same research group recently predicted that there is a 90% chance we will see the first quasi-extremal PBH blow up by 2035, which would be extremely exciting for two main reasons.

First, these explosions would be so powerful that they would probably emit "a definitive catalog of all the subatomic particles in existence," including known entities, like the Higgs boson; theorized particles, like gravitons or time-traveling tachyons; and "everything else that is, so far, entirely unknown to science," the researchers wrote in the statement.

RELATED STORIES—Atom-size black holes from the dawn of time could be devouring stars from the inside out

—A 'primordial' black hole may zoom through our solar system every decade

—Some objects we thought were planets may actually be tiny black holes from the dawn of time

Second, these black holes could help reveal the mysterious identity of dark matter — the invisible stuff that we cannot see, yet whose gravitational force we can detect within almost every observed galaxy, including the Milky Way. The researchers wrote that quasi-extremal PBHs "could constitute all of the observed dark matter in the universe," so finding one could help put this mystery to bed. (Despite the similar names, dark matter is not directly related to dark charge or dark electrons.)

The researchers, along with several other teams in the fields of physics and cosmology, are now holding their collective breath to see when the first explosion might be detected.

This "incredible event" would provide a "new window on the universe" and help us "explain this otherwise unexplainable phenomenon," study lead author Michael Baker, a theoretical physicist at UMass Amherst, said in the statement.

Article SourcesBaker, M. J., Iguaz Juan, J., Symons, A., & Thamm, A. (2025). Explaining the PeV neutrino fluxes at KM3NeT and IceCube with quasi-extremal primordial black holes. Physical Review Letters. https://doi.org/10.1103/r793-p7ct

Harry BakerSocial Links NavigationSenior Staff Writer

Harry BakerSocial Links NavigationSenior Staff WriterHarry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

View MoreYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Dark matter and neutrinos may interact, hinting at 'fundamental breakthrough' in particle physics

Dark matter and neutrinos may interact, hinting at 'fundamental breakthrough' in particle physics

Record-breaking black hole collision finally explained

Record-breaking black hole collision finally explained

First-ever 'superkilonova' double star explosion puzzles astronomers

First-ever 'superkilonova' double star explosion puzzles astronomers

Did a NASA telescope really 'see' dark matter? Strange gamma-rays spark bold claims, but scientists urge caution

Did a NASA telescope really 'see' dark matter? Strange gamma-rays spark bold claims, but scientists urge caution

'A real revolution': The James Webb telescope is upending our understanding of the biggest, oldest black holes in the universe

'A real revolution': The James Webb telescope is upending our understanding of the biggest, oldest black holes in the universe

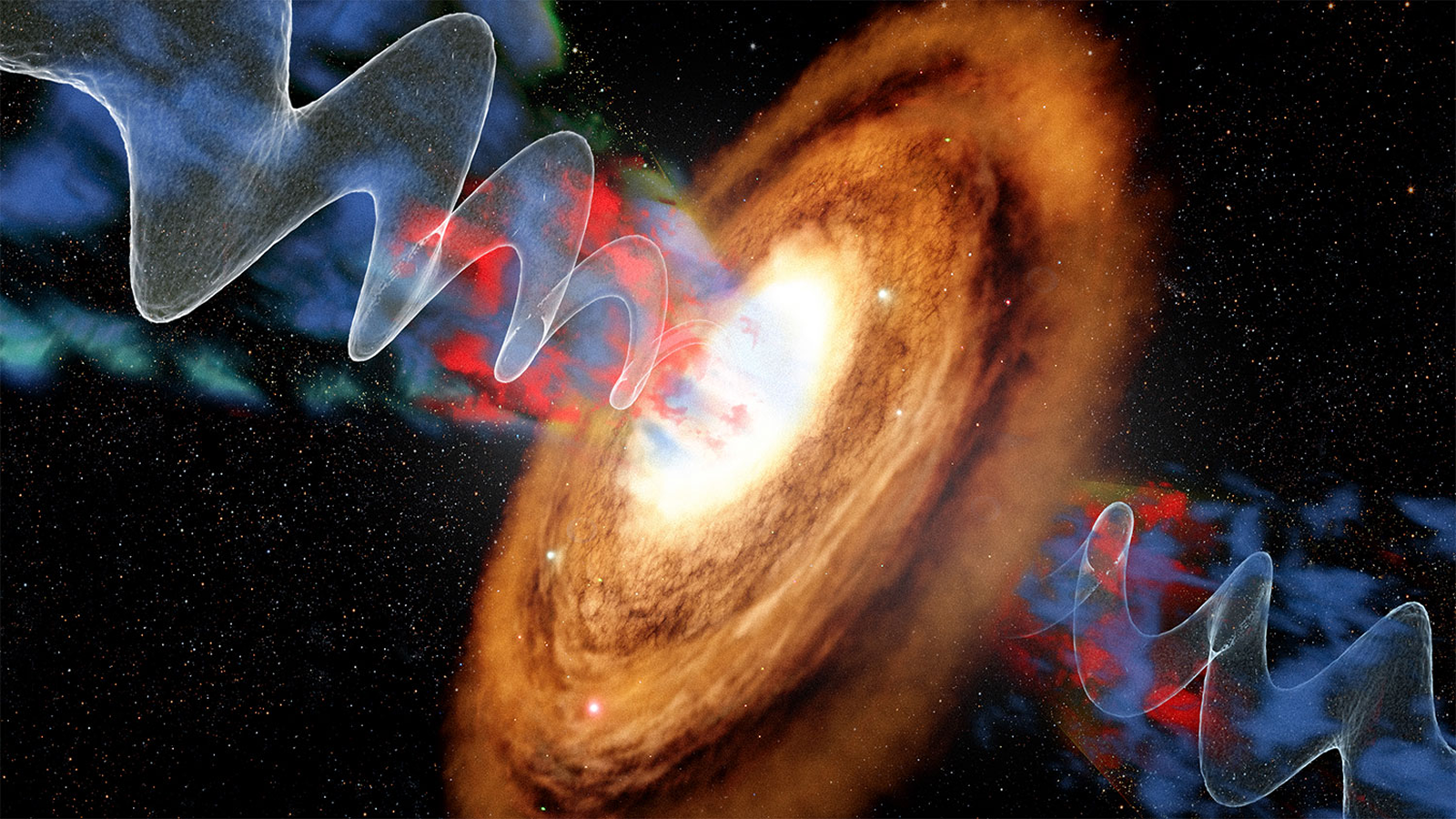

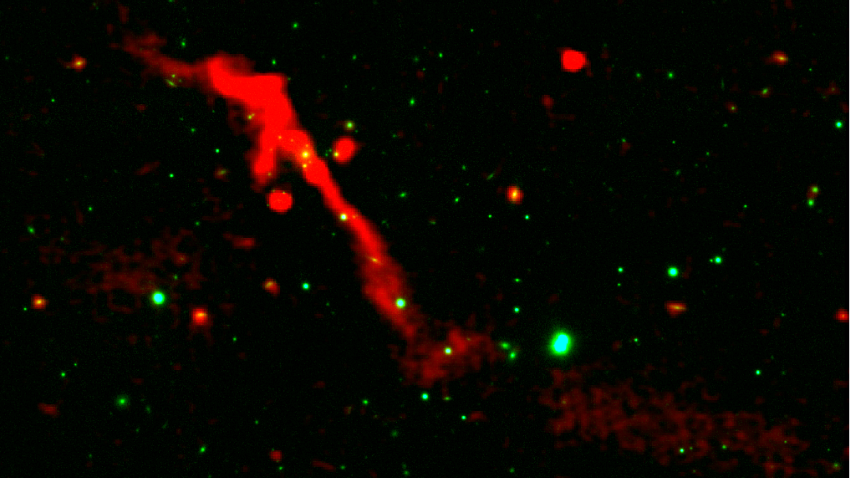

Astronomers discover a gigantic, wobbling black hole jet that 'changes the way we think about the galaxy'

Latest in Black Holes

Astronomers discover a gigantic, wobbling black hole jet that 'changes the way we think about the galaxy'

Latest in Black Holes

Star-killing black hole is one of the most energetic objects in the universe

Star-killing black hole is one of the most energetic objects in the universe

Astronomers discover a gigantic, wobbling black hole jet that 'changes the way we think about the galaxy'

Astronomers discover a gigantic, wobbling black hole jet that 'changes the way we think about the galaxy'

Scientists see monster black hole 'reborn' after 100 million years of rest

Scientists see monster black hole 'reborn' after 100 million years of rest

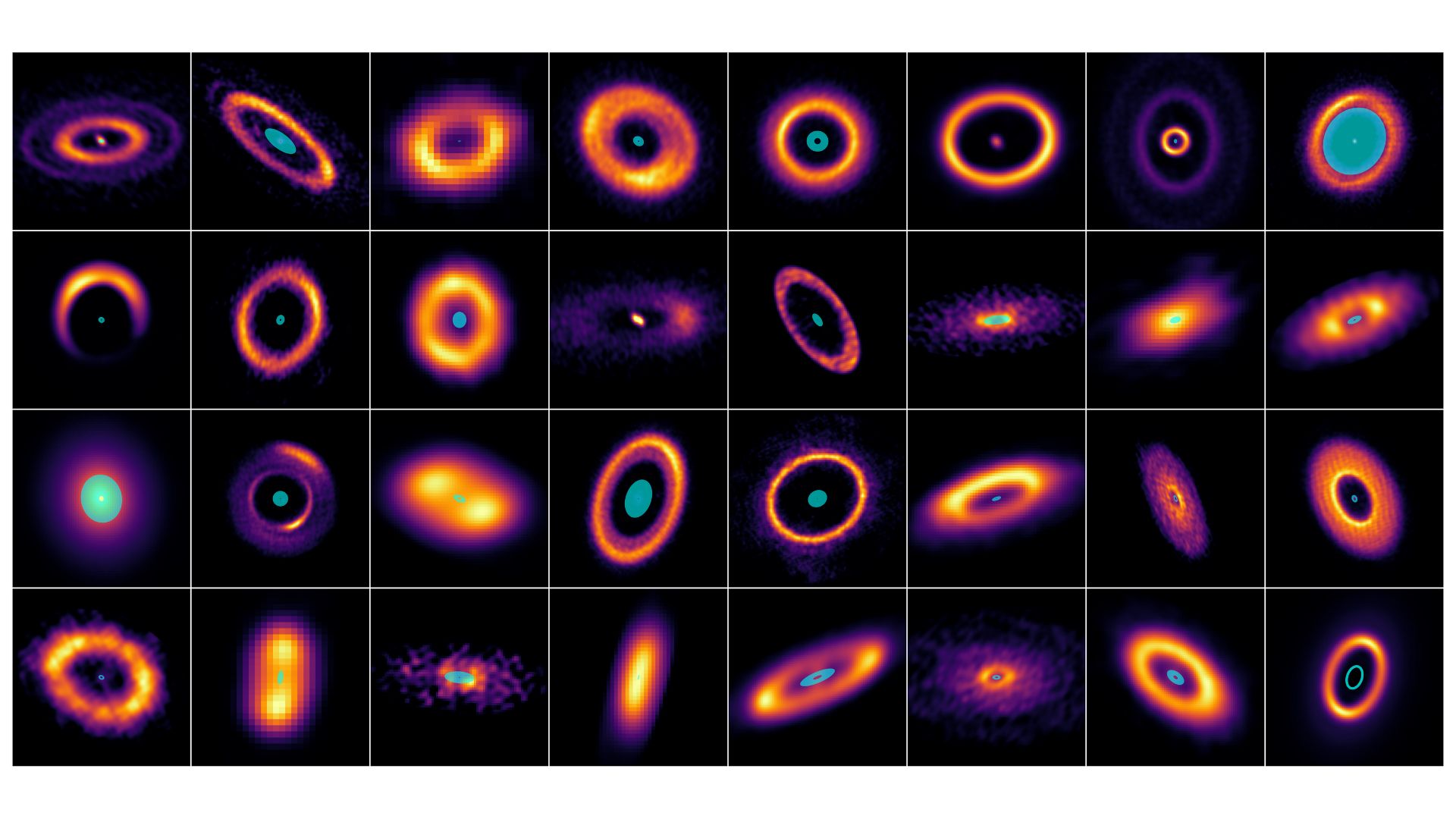

Some objects we thought were planets may actually be tiny black holes from the dawn of time

Some objects we thought were planets may actually be tiny black holes from the dawn of time

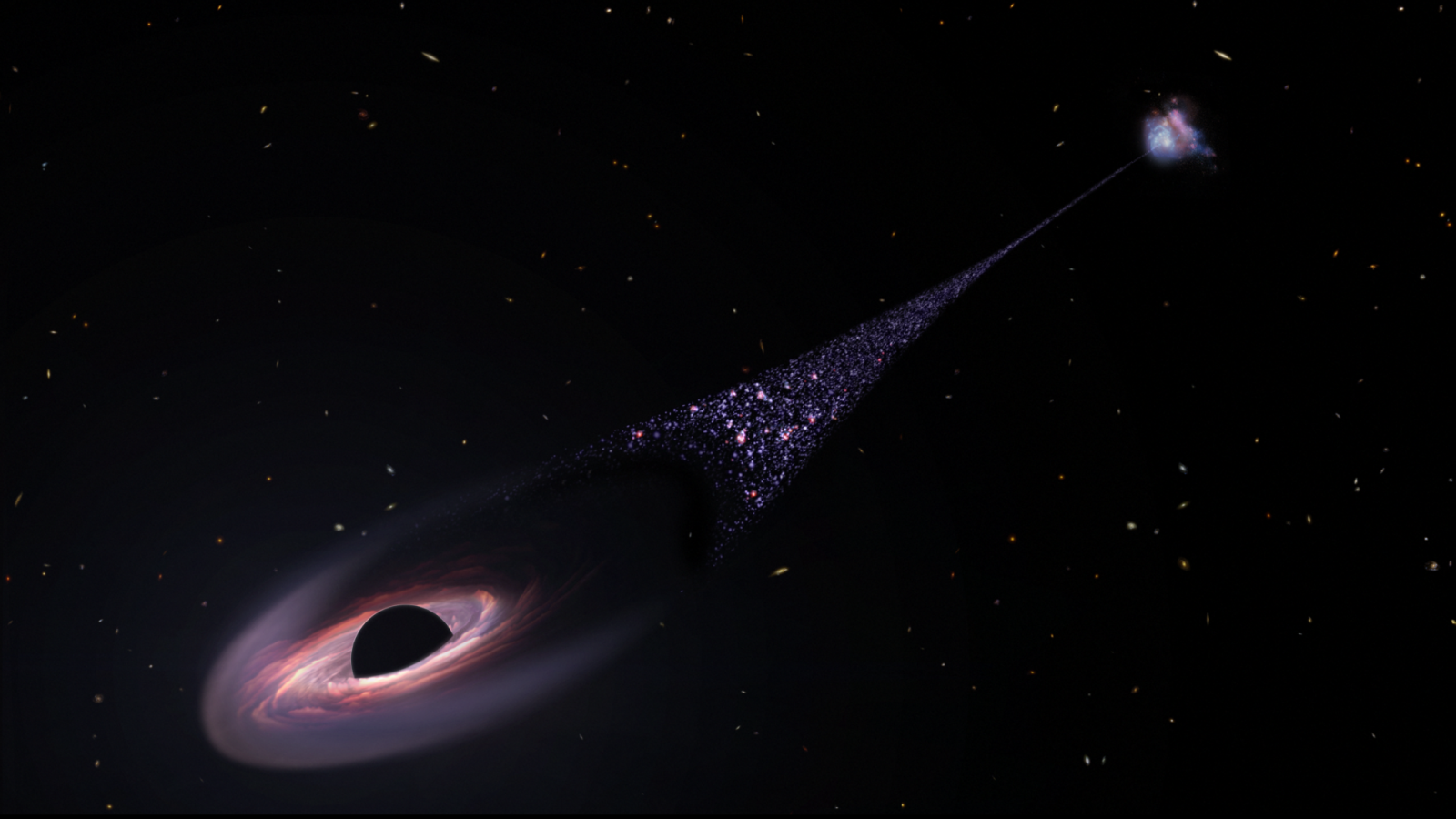

James Webb telescope confirms a supermassive black hole running away from its host galaxy at 2 million mph, researchers say

James Webb telescope confirms a supermassive black hole running away from its host galaxy at 2 million mph, researchers say

'A real revolution': The James Webb telescope is upending our understanding of the biggest, oldest black holes in the universe

Latest in News

'A real revolution': The James Webb telescope is upending our understanding of the biggest, oldest black holes in the universe

Latest in News

Impossibly powerful 'ghost particle' that hit Earth may have come from an exploding black hole

Impossibly powerful 'ghost particle' that hit Earth may have come from an exploding black hole

'There's no reason to ban us from playing': Analysis debunks notion that transgender women have inherent physical advantages in sports

'There's no reason to ban us from playing': Analysis debunks notion that transgender women have inherent physical advantages in sports

Physicists push quantum boundaries by turning a superfluid into a supersolid — and back — for the first time

Physicists push quantum boundaries by turning a superfluid into a supersolid — and back — for the first time

Paleo-Inuit people braved icy seas to reach remote Greenland islands 4,500 years ago, archaeologists discover

Paleo-Inuit people braved icy seas to reach remote Greenland islands 4,500 years ago, archaeologists discover

'Invisible scaffolding of the universe' revealed in ambitious new James Webb telescope images

'Invisible scaffolding of the universe' revealed in ambitious new James Webb telescope images

'Night owls' may have worse heart health — but why?

LATEST ARTICLES

'Night owls' may have worse heart health — but why?

LATEST ARTICLES 1Sandals of Tutankhamun: 3,300-year-old footwear that let King Tut walk all over his enemies

1Sandals of Tutankhamun: 3,300-year-old footwear that let King Tut walk all over his enemies- 2Paleo-Inuit people braved icy seas to reach remote Greenland islands 4,500 years ago, archaeologists discover

- 3'Night owls' may have worse heart health — but why?

- 4Microbes in Iceland are hoarding nitrogen, and that's mucking up the nutrient cycle

- 5Physicists push quantum boundaries by turning a superfluid into a supersolid — and back — for the first time