This crowd-curated digital movement is one of the most pertinent and explicit reactions to our particular slice of dystopian late capitalism.

Ed Simon

February 9, 2026

— 8 min read

Ed Simon

February 9, 2026

— 8 min read

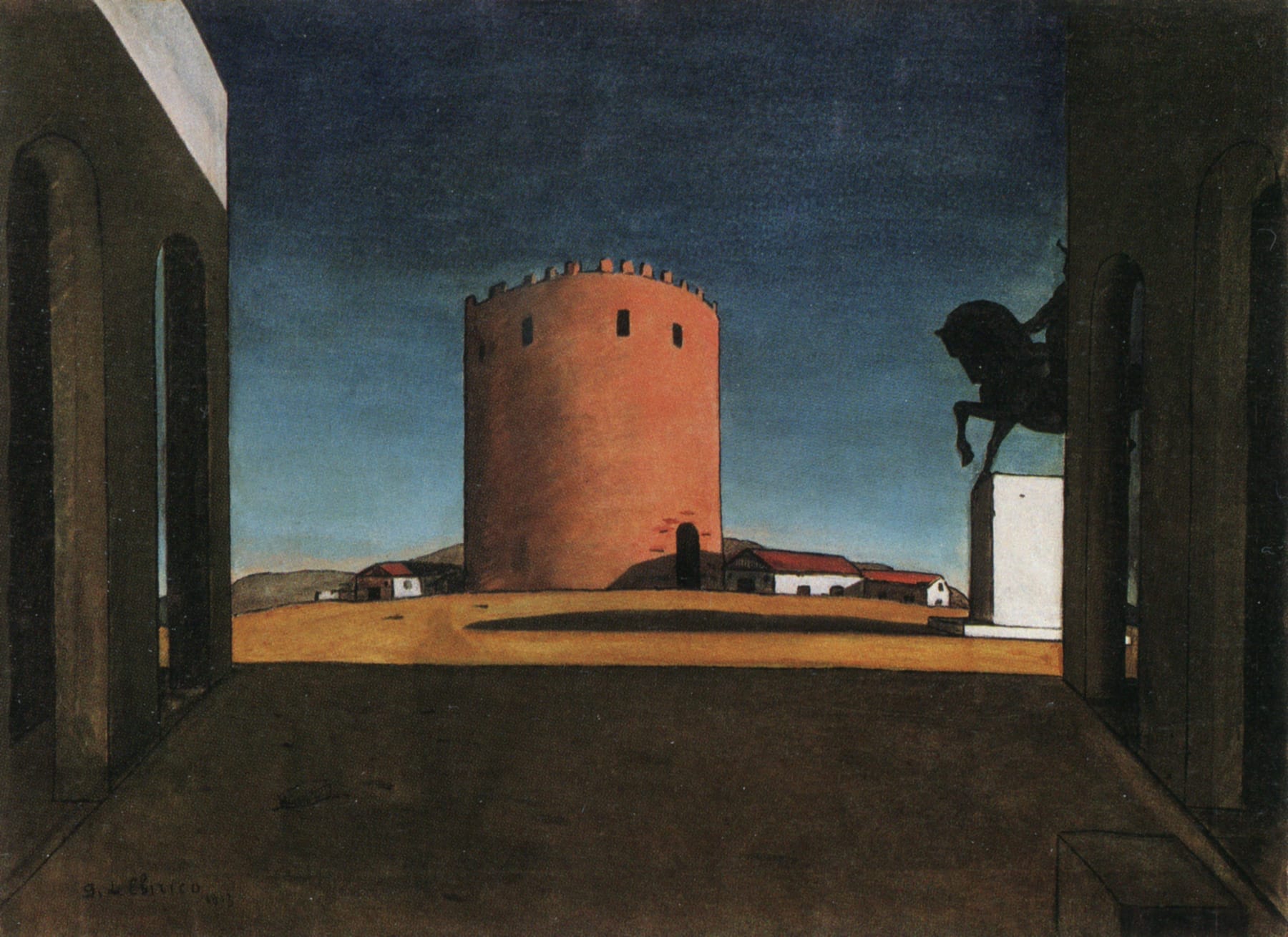

Giorgio de Chirico, "The Red Tower" (1913), oil on canvas, held by the Guggenheim Museum (photo public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Giorgio de Chirico, "The Red Tower" (1913), oil on canvas, held by the Guggenheim Museum (photo public domain via Wikimedia Commons)Had Century III Mall in West Mifflin, Pennsylvania not closed seven years ago, the shopping center — the third-largest in the world when it opened, with 200 tenants — would be approaching its 50th anniversary. Anchored by defunct local department store chains, including Joseph Horne Company, Gimbels, and Kaufmann’s, Century III had been constructed atop a slag heap — a mound of metallic industrial detritus produced as part of the steel-making process — maintained by US Steel. With a name meant to evoke the bicentennial of 1976, the mall made it four decades before finally closing like so many similar shopping centers throughout the country. Today, all that remains are the shells of a Sears, a Macy’s furniture store, and a food court, all set to be demolished soon. It’s the sort of nexus that writer Matthew Newton describes in Shopping Mall (2017) as a “ghost mall”: “places where past, present, and future simultaneously collapsed.”

Century III Mall in West Mifflin, Pennsylvania (photo Dave Columbus via Facebook)

Century III Mall in West Mifflin, Pennsylvania (photo Dave Columbus via Facebook)In an image posted by Dave Columbus to the Facebook group “liminal photography” on November 11, 2025, the sheer eeriness of the abandoned mall is evident in all of its forlorn splendor. Gray-carpeted and white-walled, the back wall features a ’70s color scheme of painted orange-and-green squares. The image exemplifies the popular internet aesthetic of “liminality”: the exploration of spaces that appear “in between,” that are uncanny and uncomfortable despite being mundane or familiar. Emptied of stores and absent of humans, Columbus’s photograph captures the melancholic discomfort of liminal aesthetics — the strange, simultaneous pull of disquiet and nostalgia that makes this bottom-up, crowd-curated digital movement among the most pertinent and explicit artistic reactions to the strange, surreal experience of living in our particular moment of dystopian late capitalism.

Popular Internet meme known as "The Backrooms," first pulished in 2011 (photo via Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0)

Popular Internet meme known as "The Backrooms," first pulished in 2011 (photo via Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0)As an internet phenomenon, the most recent iteration of liminal aesthetics can be primarily traced to a 2019 Creepypasta collaborative short story entitled “The Backrooms,” which first appeared on the message board 4chan. Inspired by an unsettling and depressing image of a yellowed commercial backroom with fluorescent lighting and dirty carpets, devoid of either furniture or people, it imagined the space depicted (in reality, a hobby shop in Oshkosh, Wisconsin in 2003) as a kind of interdimensional realm of recursive, infinite variations. An anonymous poster in 2019 described the concept of the “Backrooms” as being constituted by “nothing but the stink of old moist carpet, the madness of mono-yellow, the endless background noise of fluorescent lights … [across] approximately six hundred million square miles of randomly segmented empty rooms.”

The purgatorial realm of “Backrooms” lore is composed of these non-spaces — a dimension of empty airport lobbies and hotel hallways, offices at night and closed grocery stores. A cross between the stories of Jorge Luis Borges and Mark Z. Danielewski, the mythos sparked a vibrant online community. So popular was “The Backrooms” that a YouTube series based on the (otherwise public domain) subject has been optioned for an A24 film.

@unicosobreviviente Responder a @memide.23 ♬ sonido original - Único Sobreviviente

Central to the liminal aesthetic, whether in “The Backrooms” or otherwise, is the complete absence of humans, whereby the viewer of the image must imagine herself as the only person in the scene. This intentionally alienating experience — a personal loneliness that’s borderline apocalyptic — is similar to the feeling conveyed by the Spanish TikToker Javier’s 2021 clips, in which he claimed to have time-traveled to 2027, and saw that normally bustling social and commercial spaces were now totally devoid of human beings. Filmed during the 2020 COVID-19 shutdowns, Javier’s short films hover at the margins of the broader popularity of the liminal aesthetic, which was perfectly attuned to the surreal incongruity of shutdowns as well as the digital siloing of individuals, as smartphones became more omnipresent and social bonds subsequently further frayed.

While “The Backrooms” is a popular iteration of the aesthetic, most examples of the liminal are untethered from any particular narrative — an organic art movement of found images curated for the psychological effect they inculcate, equal parts uneasiness and mystery. As Karl Emil Koch put it in Musée Magazine: the “type of emotional space that conveys … nostalgia, lostness, and uncertainty … spaces of transition — of becoming instead of being.” Certainly, the aesthetic is of our zeitgeist. Look to the numbers alone: A Facebook group named “Liminal Spaces” has 228,000 followers sharing images, while “Liminal Photography” numbers 357,300. r/LiminalSpace on Reddit welcomes 136,000 weekly visitors.

A running track at a gym (photo u/PresentEuphoric2216 via Reddit)

A running track at a gym (photo u/PresentEuphoric2216 via Reddit)Notably, such communities explicitly prohibit AI-generated content — though such works often share a similar feel of foreboding, liminal communities intentionally feature unsettling, even surreal, pictures from the actual world. In this manner, Liminalism (if we can christen this as a movement, and we should) is a form dedicated to the discovery of digital found art. It is important not just because of its content, but because it signals the migration of critical terminology and thinking into popular discourse in a truly democratic sense, independent of the traditional confines of the art industry as expressed in exhibitions, galleries, and museums.

A photo of balconies that recalls the spatial disorientation of Giorgio de Chirico (photo u/MysticMind89 via Reddit)

A photo of balconies that recalls the spatial disorientation of Giorgio de Chirico (photo u/MysticMind89 via Reddit)Within the canon of Liminalism, there are some notable masterpieces — those among the most upvoted and shared images across communities dedicated to the aesthetic. A dreary, carpeted, curved, windowless hallway where a dead tree is placed in a nook as some kind of decoration, an appearance as incongruous as a locomotive emerging from a fireplace in a René Magritte painting. A series of sun-dappled balconies composed of red stucco viewed in alternating angles, recalling the cracked perspective and spatial disorientation of a Giorgio de Chirico composition. An indoor running track cutting through a claustrophobically tight curved hallway, trapping the viewer. An underground university pedestrian tunnel decorated with a garish and vertiginous orange-and-red circular pattern that’s evocative of the dizzying angles of German Expressionism. A long, red-carpeted hallway, perhaps at an airport, that reminds one of a Stanley Kubrick still, whether the numerous passageways in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) or the cursed hallways of the Overlook Hotel in The Shining (1980).

Indeed, Liminalism’s lineage runs deeply through art history. The connection to Surrealism is intuitively obvious, even while Liminalist works avoid the flat-out bizarreness of the more extreme examples of that century-old avant-garde — think Magritte or de Chirico over Dalí. See, for instance, the long, terminating perspective; empty, alienating landscape; and sparse, minimalist architecture of a work like de Chirico’s 1913 “Plaza,” now on view at Argentina’s National Foundation of the Arts. Or Magritte’s Empire of Light series, painted from the 1940s to '60s, which frequently features a strangely lit country house where it appears to be daytime in the sky but night at ground level.

Semi-abandoned underground hall (photo u/Which-Crab-638 via Reddit)

Semi-abandoned underground hall (photo u/Which-Crab-638 via Reddit)More than the European Modernists, however, Liminalism has its precedents in the equally — maybe more — disturbing works of American postwar masters, whose oeuvres have sometimes been unfairly dismissed as less revolutionary than their contemporaries in Paris, Berlin, or Zurich. Grant Wood, as much a genius of the counterintuitive nightmarish as any painter who put brush to canvas, is too often dismissed as the pablum purveyor of “American Gothic” (1930) (which has its own brilliance), but his series of immersive murals, Corn Room (1926), exhibited at the Sioux City Art Center in Iowa, conveys a skeletal yellow alienation the same hue as a fluorescent backroom. Andrew Wyeth, who, like Wood, is sometimes skipped over by embarrassed arts cognoscenti even while he can’t be entirely dismissed, engaged with similar themes of rural loneliness. While the presence of the eponymous subject in the 1948 painting "Christina’s World" (at the Museum of Modern Art) precludes it from being considered strictly liminal, the vaguely terrifying house on the horizon between an autumnal hillside and a charcoal-gray sky she crawls toward is evocative of the contemporary movement.

Edward Hopper, "Early Sunday Morning" (1930), oil on canvas, held at the Whitney Museum of American Art (photo public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Edward Hopper, "Early Sunday Morning" (1930), oil on canvas, held at the Whitney Museum of American Art (photo public domain via Wikimedia Commons)Obviously, the clearest thematic precursor to Liminalism is Edward Hopper. There is a stolid, individualistic, bootstrapping Protestant work ethic element to Hopper’s work, which is, in its sheer insanity, the wellspring of the alienation implicit in Liminalism. Even while Hopper was a master at depicting an assemblage of people alone despite being together, the American artist was particularly adept at envisioning alienating and isolating landscapes devoid of humans. "Early Sunday Morning," painted in 1930 and now owned by the Whitney Museum of American Art, depicts a long line of connected red-brick New York rowhouses, light filtering down the desolate street in a vaguely unnatural way. Ten years later, his "Gas" presents that eponymous subject at dusk on a lonely country road, the presence of a single customer at a pump so subtle as to be missed at first. Then there is "Sun in an Empty Room," from 1963 (held in private collection and promised to the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas), a forlorn, sparse, white-walled room based on his Cape Cod summer house that looks like it could have been taken directly from r/LiminalSpaces.

Edward Hopper, "Gas" (1940), oil on canvas, on view at the Museum of Modern Art (photo public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Edward Hopper, "Gas" (1940), oil on canvas, on view at the Museum of Modern Art (photo public domain via Wikimedia Commons)“The discourse of liminality itself is perhaps a symptom of cartographic anxiety or spatial confusion characteristic of the present moment,” writes Robert T. Tally Jr. in his foreword to the anthology Landscapes of Liminality: Between Space and Place (2016), edited by Dara Downey, Ian Kinane, and Elizabeth Parker. Indeed, despite its long roots in tradition, Liminalism is expressly of our own moment. The placelessness of Liminalism — these spaces could notably be anywhere — flattens experience in the same way that digital homogenization obliterates distance. Anonymity, alienation, and anxiety are now the bywords of our age, and Liminalism is the ultimate expression of that trinity.

COVID-19 may have hyper-charged interest in the aesthetic, but its attractions predate and outlast those shutdowns now six years in the past. By presenting spaces stripped of people, Liminalism conveys the emptiness of the now, the hyperreality of the present where the no-place serves to make us feel — or suspect — that all of this is a simulation, a bit of code that threatens to transport us into the Backrooms. Its medium of dissemination through anonymous message boards and TikToks isn’t incidental to its content but a constituent part of it. This is internet art — it only has the emotional resonance it does because of how it’s produced, disseminated, and consumed. An aesthetic of digital movement, of people siloed into the atomistic dimension of the smartphone (even, or maybe especially, if they’re otherwise in “public”).

In Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (2014), critical theorist Mark Fisher describes the generational affliction of being “walled off from the lifeworld, so that … inner life — or inner death — overwhelms everything,” where there is “nothing but the inside, but the inside is empty.” It's an apt summation of Liminalism — the visual accompaniment to neoliberalism, post-industrialization, early apocalypse, whatever you want to call it, as silent and dark as an abandoned shopping mall.