An exhibition about the influence of French critical theory on American art finds inspiration in diasporic thinkers like Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire.

Cat Dawson

February 11, 2026

— 4 min read

Cat Dawson

February 11, 2026

— 4 min read

A work from Melvin Edwards's Lynch Fragments series (begun 1963) in Echo Delay Reverb: American Art, Francophone Thought at Palais de Tokyo (all photos Cat Dawson/Hyperallergic)

A work from Melvin Edwards's Lynch Fragments series (begun 1963) in Echo Delay Reverb: American Art, Francophone Thought at Palais de Tokyo (all photos Cat Dawson/Hyperallergic)

PARIS — Echo Delay Reverb: American Art, Francophone Thought at Palais de Tokyo is billed as an exploration of the influence of French critical theory — including and perhaps especially thinkers in Francophone Africa and the Caribbean such as Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire — on American art. For those who have encountered critical theory and indulge in the occasional Marx meme, the show may sound like catnip, but such conceits often slip into theory- and text-heavy curation that is opaque to many viewers. So it was refreshing to find the exhibition’s theoretical points concisely made, historically situated, and woven through excellent wall labels that contextualize a wealth of strong artworks.

The show, which is staged across nearly all the museum’s available space, truly begins with pioneering abstract sculptor Melvin Edwards, whose work has its own space that viewers have to walk through to enter the main galleries. The pieces on view range from his small Lynch Fragments series to larger installations composed of barbed wire or sizable industrial objects — some freighted with meaning, such as a short length of chain or shackle, others more ambiguous, like a finial or a single metal cube — that play up the works’ formal qualities: the heavy made to look impossibly light, the razor sharp to appear delicate. Edwards’s sculptures lay bare the ways in which the material realities of labor, incarceration, and death still evoke violent associations even when the machines that enable those processes are broken out into component parts.

Installation view of Fred Wilson’s “Dear End" (2023)

Installation view of Fred Wilson’s “Dear End" (2023)Edwards has long been in conversation with transatlantic networks of poets and theorists, including Léon Gontran Damas, whom he met through the Black Arts Movement, and Jayne Cortez, whom he married in 1975, and his art reflects much of the critical theory that undergirds the show. “Maquette for a sculpture in homage to Édouard Glissant” (2021) speaks to the belated recognition of diasporic Francophone thought on contemporary discourse: Born in 1928 in Martinique, Glissant moved to Paris for his doctoral work, then returned to Martinique to found the Institut Martiniquais D’études; there, he began to produce a body of work on coloniality, social movements, and the afterlives of the Atlantic slave trade, all of which are unavoidable in contemporary scholarly discourse.

The main show begins with Fred Wilson’s “Dear End" (2023), an array of oversized, wall-mounted glass droplets. Though widely circulated online and in art publications, it is born out in person to be impossible to capture, the nuances of the hollow blown glass forms utterly resistant to photographic reproduction. Wilson’s citation of capture, and almost absurd enlargement of the droplet form, exemplify artistic and critical strategies of addressing the questions and consequences of imperialism, enslavement, and the diasporic condition, while refusing to be reducible exclusively to those themes.

Cici Wu's tribute to Theresa Hak Kyung Cha

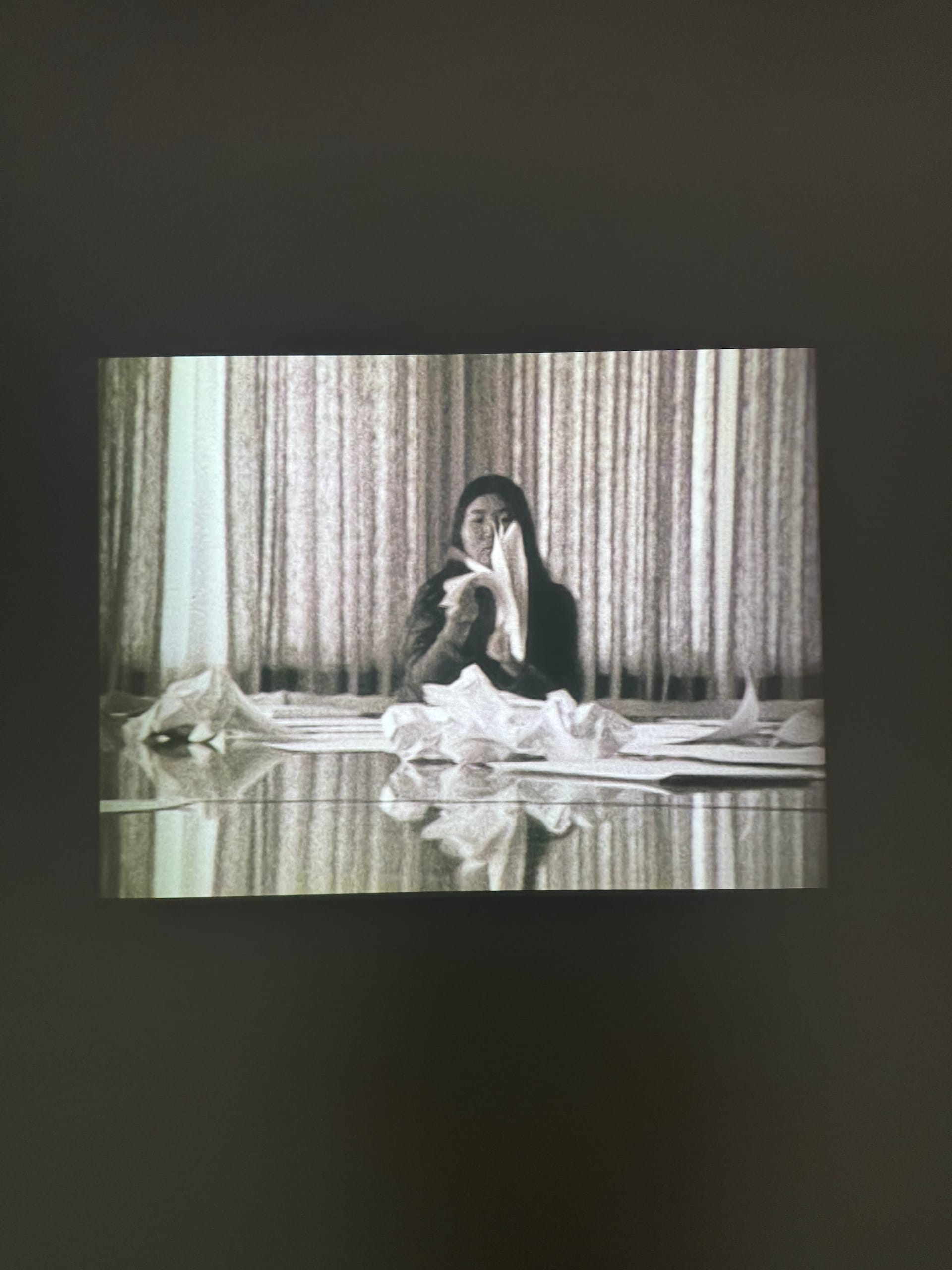

Cici Wu's tribute to Theresa Hak Kyung ChaThough it includes blockbuster works and artists, the real revelations in Echo Delay Reverb come from some of the less widely known artists whose work is given space to breathe, expand, and connect across continents and generations. A room housing several of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s poststructuralist forays into film is adjacent to Cici Wu’s delicate but haunting tribute to the artist — who was raped and murdered at the age of 31. Wu’s installation of light boxes and other small objects physically expands on text and image fragments from Cha’s archive that take up questions of race, gender, and age. Other standouts include a selection of photographs, ranging from sweeping cityscapes to intimate shots of plants, by Miami-based Haitian-American artist Adler Guerrier. They’re accompanied by swatches of paint from South Florida that have diasporic symbolism; the colors can be found in neighborhoods in Haiti and elsewhere in the Caribbean as easily as in Florida.

Echo Delay Reverb leaves ambiguous the indexicality between the artworks and the theorists’ scholarly output. But by articulating the centrality of Caribbean thinkers to the French thought that structures the show, it makes an important and public-facing contribution to a larger project that’s often limited to academic circles: It communicates the significance of revolutionary diasporic thought to contemporary scholarship about the operations of power — with particular attention to the Caribbean theorists whose work remains under-recognized in academia compared to their White, French counterparts.

Yet even if viewers disregard this facet, the show is a pleasure to digest. While that might sound like a bug rather than a feature, it felt essential — for a show grounded in the abstract world of critical theory, Echo Delay Reverb is remarkably inviting.

Still from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, "Untitled (Paper)" (1975)

Still from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, "Untitled (Paper)" (1975)Echo Delay Reverb: American Art, Francophone Thought continues at Palais de Tokyo (13 avenue du Président Wilson, Paris, France) through February 15. The exhibition was curated by Naomi Beckwith with James Horton, Amandine Nana, and François Piron, assisted by Vincent Neveux, Romane Tassel, and Morgane Padellec.