- Archaeology

Gender-ambiguous people in ancient Mesopotamia were powerful and important members of society more than four millennia ago.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

An eighth-century B.C. relief of a king and his chief ša rēši, from what is now Iraq.

(Image credit: Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago. OIM A7366. Daderot/Wikimedia Commons/Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago. OIM A7366)

Share

Share by:

An eighth-century B.C. relief of a king and his chief ša rēši, from what is now Iraq.

(Image credit: Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago. OIM A7366. Daderot/Wikimedia Commons/Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago. OIM A7366)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Today, trans people face politicization of their lives and vilification from politicians, media and parts of broader society.

But in some of history's earliest civilizations, gender-diverse people were recognized and understood in a wholly different way.

As early as 4,500 years ago in ancient Mesopotamia, for instance, gender-diverse people held important roles in society with professional titles. These included the cultic attendants of the major deity Ištar, called assinnu, and high-ranking royal courtiers called ša rēši.

You may like-

5,000-year old 'cultic space' discovered in Iraq dates to time of the world's first cities

5,000-year old 'cultic space' discovered in Iraq dates to time of the world's first cities

-

'I screamed out of excitement': 2,700-year-old cuneiform text found near Temple Mount — and it reveals the Kingdom of Judah had a late payment to the Assyrians

'I screamed out of excitement': 2,700-year-old cuneiform text found near Temple Mount — and it reveals the Kingdom of Judah had a late payment to the Assyrians

-

Male human heads found in a 'skull pit' in an ancient Chinese city hint at sex-specific sacrifice rituals

Male human heads found in a 'skull pit' in an ancient Chinese city hint at sex-specific sacrifice rituals

What the ancient evidence tells us is that these people held positions of power because of their gender ambiguity, not despite it.

Where is Mesopotamia and who lived there?

Mesopotamia is a region primarily made up of modern Iraq, but also parts of Syria, Turkey and Iran. Part of the Fertile Crescent, Mesopotamia is a Greek word which literally means "land between two rivers", referring to the Euphrates and Tigris.

For thousands of years, several different major cultural groups lived there. Amongst these were the Sumerians, and the later Semitic groups called the Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians.

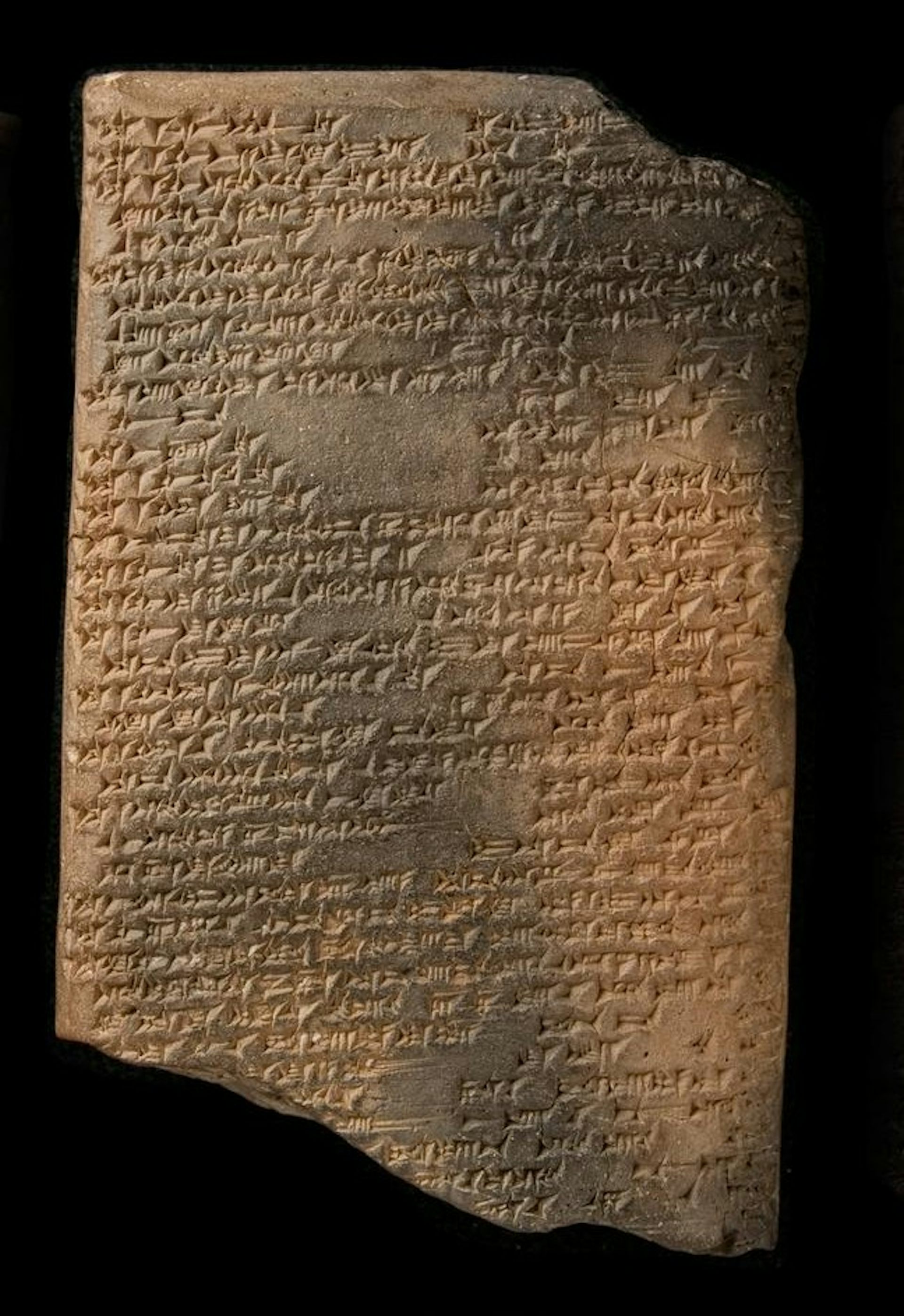

The Sumerians invented writing by creating wedges on clay tablets. The script, called cuneiform, was made to write the Sumerian language but would be used by the later civilizations to write their own dialects of Akkadian, the earliest Semitic language.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.Who were the assinnu?

The assinnu were the religious servants of the major Mesopotamian goddess of love and war, Ištar.

The queen of heaven, Ištar was the precursor to Aphrodite and Venus.

Also known by the Sumerians as Inanna, she was a warrior god, and held the ultimate political power to legitimize kings.

You may like-

5,000-year old 'cultic space' discovered in Iraq dates to time of the world's first cities

5,000-year old 'cultic space' discovered in Iraq dates to time of the world's first cities

-

'I screamed out of excitement': 2,700-year-old cuneiform text found near Temple Mount — and it reveals the Kingdom of Judah had a late payment to the Assyrians

'I screamed out of excitement': 2,700-year-old cuneiform text found near Temple Mount — and it reveals the Kingdom of Judah had a late payment to the Assyrians

-

Male human heads found in a 'skull pit' in an ancient Chinese city hint at sex-specific sacrifice rituals

Male human heads found in a 'skull pit' in an ancient Chinese city hint at sex-specific sacrifice rituals

She also oversaw love, sexuality and fertility. In the myth of her journey to the Netherworld, her death puts an end to all reproduction on Earth. For the Mesopotamians, Ištar was one of the greatest deities in the pantheon. The maintenance of her official cult ensured the survival of humanity.

As her attendants, the assinnu were responsible for pleasing and tending to her through religious ritual and the upkeep of her temple.

The title assinnu is an Akkadian word related to terms that mean "woman-like" and "man-woman", as well as "hero" and "priestess."

Their gender fluidity was bestowed on them by Ištar herself. In a Sumerian hymn, the goddess is described as having the power to

turn a man into a woman and a woman into a man

to change one into the other

to dress women in clothes for men

to dress men in clothes for women

to put spindles into the hands of men

and to give weapons to women.

The assinnu were viewed by some early scholars as a type of religious sex worker. This, however, is based on early assumptions about gender-diverse groups, and is not well supported by evidence.

The title is also often translated as "eunuch," though there is also no clear evidence they were castrated men. While the title is primarily masculine, there is evidence of female assinnu. In fact, various texts show they resisted the gender binary.

Their religious importance allowed them to possess magical and healing powers. An incantation states:

May your assinnu stand by and extract my illness. May he make the illness which seized me go out the window.

And a Neo-Assyrian omen tells us that sexual relations with an assinnu could bring personal benefits:

If a man approaches an assinnu [for sex]: restrictions will be loosened for him.

As the devotees of Ištar, they also had powerful political influence. A Neo-Babylonian almanac states:

[the king] should touch the head of an assinnu, he shall defeat his enemy his land will obey his command.

Having their gender transformed by Ištar herself, the assinnu could walk between the divine and the mortal as they maintained the wellbeing of both the gods and humanity.

Who were the ša rēši?

Usually described as eunuchs, the ša rēši were attendants to the king.

Court "eunuchs" have been recorded in many cultures throughout history. However, the term did not exist in Mesopotamia, and the ša rēši had their own distinct title.

The Akkadian term ša rēši literally means "one of the head", and refers to the king's closest courtiers. Their duties in the palace varied, and they could hold several high-ranking posts at the same time.

The evidence for their gender ambiguity is both textual and visual. There are various texts that describe them as infertile, such as an incantation which states:

Like a ša rēši who does not beget, may your semen dry up!

The ša rēši are always depicted beardless, and were contrasted with another type of courtier called ša ziqnī ("bearded one"), who had descendants. In Mesopotamian cultures, beards signified one's manhood, and so a beardless man would go directly against the norm. Yet, reliefs show the ša rēši wore the same dress as other royal men, and so were able to display authority alongside other elite males.

One of their main functions was supervising the women's quarters in the palace — a place of highly restricted access — where the only male permitted to enter was the king himself.

As they were so closely trusted by the king, they were not only able to hold martial roles as guards and charioteers, but also lead their own armies. After their victories, ša rēši were granted property and governorship over newly conquered territories, as evidenced by one such ša rēši who erected their own royal stone inscription.

Because of their gender fluidity, the ša rēši were able to transcend the boundaries of not just gendered space, but that between ruler and subject.

Gender ambiguity as a tool of power

RELATED STORIES—Are Mesopotamia and Babylon the same thing?

—Mesopotamia quiz: Test your knowledge about the ancient civilizations of the Fertile Crescent

—Massive Mesopotamian canal network unearthed in Iraq

While early historians understood these figures as "eunuchs" or "cultic sex workers", the evidence shows it was because they lived unbound by the gender binary that these groups were able to hold powerful roles in Mesopotamian society.

As we recognize the importance of transgender and gender-diverse people in our communities today, we can see this as a continuity of respect given to these early figures.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Chaya KasifPhD Candidate; Assyriologist, Macquarie University

Chaya KasifPhD Candidate; Assyriologist, Macquarie UniversityChaya Kasif is an Assyriologist interested in gender and sexuality in ancient Mesopotamia, as well as ancient languages and translation theory. Kasif has completed a Bachelor of Ancient History at Macquarie University, as well as a Master of Philosophy in Assyriology at the University of Cambridge, where Kasif ranked first in cohort and was awarded the department prize for Excellence in Ancient Languages (Akkadian). Kasif is currently a PhD candidate at Macquarie University where Kasif's thesis project develops a philological analysis of sexuality in Neo-Assyrian divination texts.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more 5,000-year old 'cultic space' discovered in Iraq dates to time of the world's first cities

5,000-year old 'cultic space' discovered in Iraq dates to time of the world's first cities

'I screamed out of excitement': 2,700-year-old cuneiform text found near Temple Mount — and it reveals the Kingdom of Judah had a late payment to the Assyrians

'I screamed out of excitement': 2,700-year-old cuneiform text found near Temple Mount — and it reveals the Kingdom of Judah had a late payment to the Assyrians

Male human heads found in a 'skull pit' in an ancient Chinese city hint at sex-specific sacrifice rituals

Male human heads found in a 'skull pit' in an ancient Chinese city hint at sex-specific sacrifice rituals

'A huge surprise': 1,500-year-old church found next to Zoroastrianism place of worship in Iraq

'A huge surprise': 1,500-year-old church found next to Zoroastrianism place of worship in Iraq

Were there female gladiators in ancient Rome?

Were there female gladiators in ancient Rome?

12,000-year-old figurine of goose mating with naked woman discovered in Israel

Latest in Archaeology

12,000-year-old figurine of goose mating with naked woman discovered in Israel

Latest in Archaeology

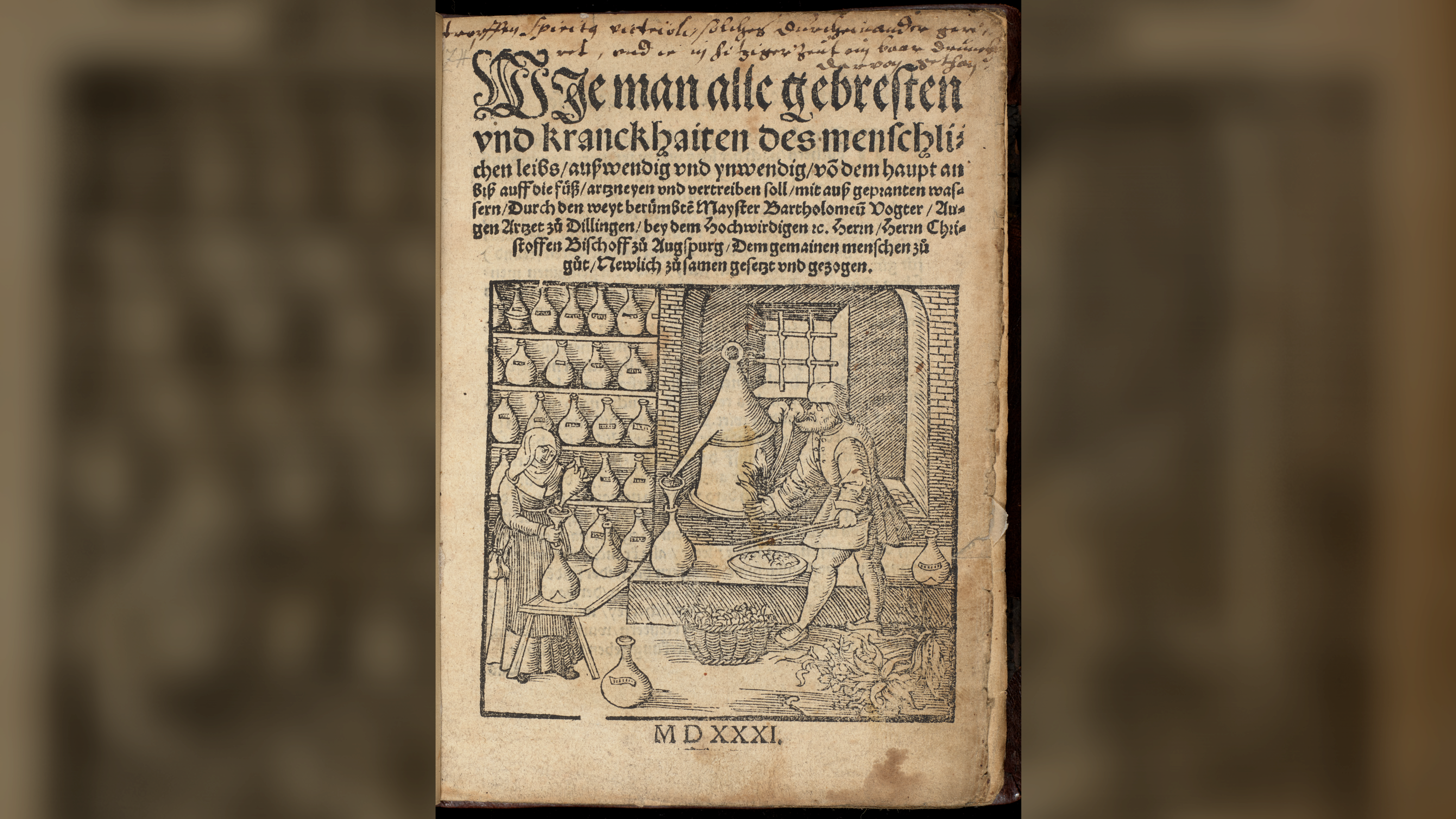

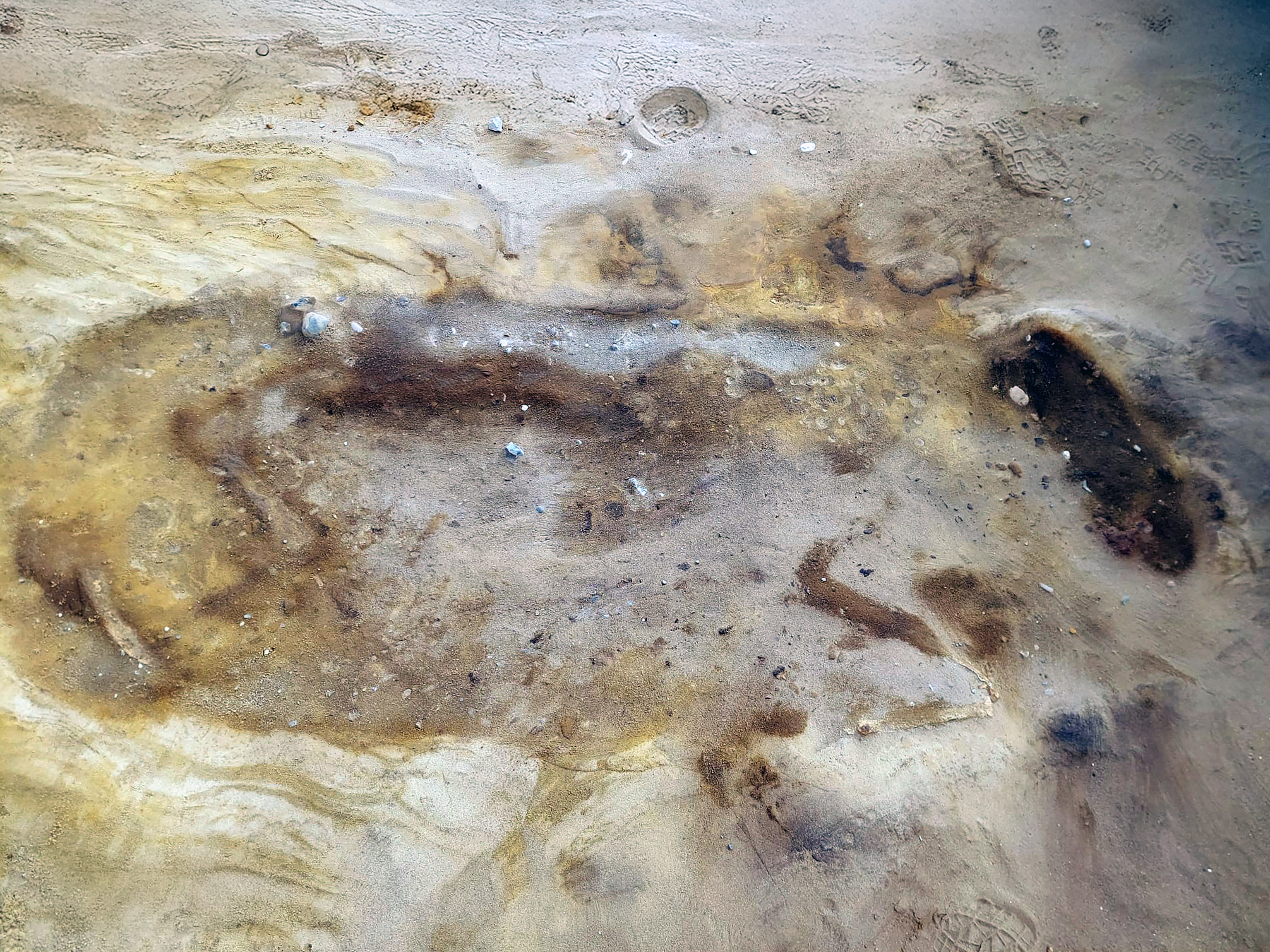

Remnants of spills on Renaissance-era textbook reveal recipes for 'curing' ailments with lizard heads and human feces

Remnants of spills on Renaissance-era textbook reveal recipes for 'curing' ailments with lizard heads and human feces

Romans regularly soaked in filthy, lead-contaminated bath water, Pompeii study finds

Romans regularly soaked in filthy, lead-contaminated bath water, Pompeii study finds

Eerie 'sand burials' of elite Anglo-Saxons and their 'sacrificed' horse discovered near UK nuclear power plant

Eerie 'sand burials' of elite Anglo-Saxons and their 'sacrificed' horse discovered near UK nuclear power plant

Nefertiti's tomb close to discovery, famed archaeologist Zahi Hawaas claims in new documentary

Nefertiti's tomb close to discovery, famed archaeologist Zahi Hawaas claims in new documentary

Most complete Homo habilis skeleton ever found dates to more than 2 million years ago and retains 'Lucy'-like features

Most complete Homo habilis skeleton ever found dates to more than 2 million years ago and retains 'Lucy'-like features

How the ancient Romans managed their wealth (it wasn't just by hiding hoards)

Latest in Opinion

How the ancient Romans managed their wealth (it wasn't just by hiding hoards)

Latest in Opinion

Is there anything 'below' Earth in space?

Is there anything 'below' Earth in space?

NASA launches Pandora telescope, taking JWST's search for habitable worlds to a new level

NASA launches Pandora telescope, taking JWST's search for habitable worlds to a new level

'The scientific cost would be severe': A Trump Greenland takeover would put climate research at risk

'The scientific cost would be severe': A Trump Greenland takeover would put climate research at risk

Gender ambiguity was a tool of power 4,500 years ago in Mesopotamia

Gender ambiguity was a tool of power 4,500 years ago in Mesopotamia

Should humans colonize other planets?

Should humans colonize other planets?

'Gospel stories themselves tell of dislocation and danger': A historian describes the world Jesus was born into

LATEST ARTICLES

'Gospel stories themselves tell of dislocation and danger': A historian describes the world Jesus was born into

LATEST ARTICLES 1HP Omen Max 16 (2025) review: This heavyweight pushes everything to the max

1HP Omen Max 16 (2025) review: This heavyweight pushes everything to the max- 2Eerie 'sand burials' of elite Anglo-Saxons and their 'sacrificed' horse discovered near UK nuclear power plant

- 3Last year, the oceans absorbed a record-breaking amount of heat — equivalent to 12 Hiroshima bombs exploding every second

- 4Remnants of spills on Renaissance-era textbook reveal recipes for 'curing' ailments with lizard heads and human feces

- 5Motorola Moto Watch Fit fitness tracker review: The perfect yoga companion