- Physics & Mathematics

- Dark Energy

Our best models of the cosmos don't add up — but that could change if the universe is actually made of a viscous 'fluid,' a new paper suggests.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

What if space is much more liquid-like than we thought? New research says it could solve a major cosmological problem.

(Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI, J. DePasquale (STScI))

Share

Share by:

What if space is much more liquid-like than we thought? New research says it could solve a major cosmological problem.

(Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI, J. DePasquale (STScI))

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Recent observations have revealed that our understanding of the cosmos is flawed, but it may be because the universe is "stickier" than we assumed, new research proposes.

In a paper that was published on the arXiv preprint server but has not been peer-reviewed, Muhammad Ghulam Khuwajah Khan, a researcher at the Indian Institute of Technology, suggests that space may possess a property called bulk viscosity.

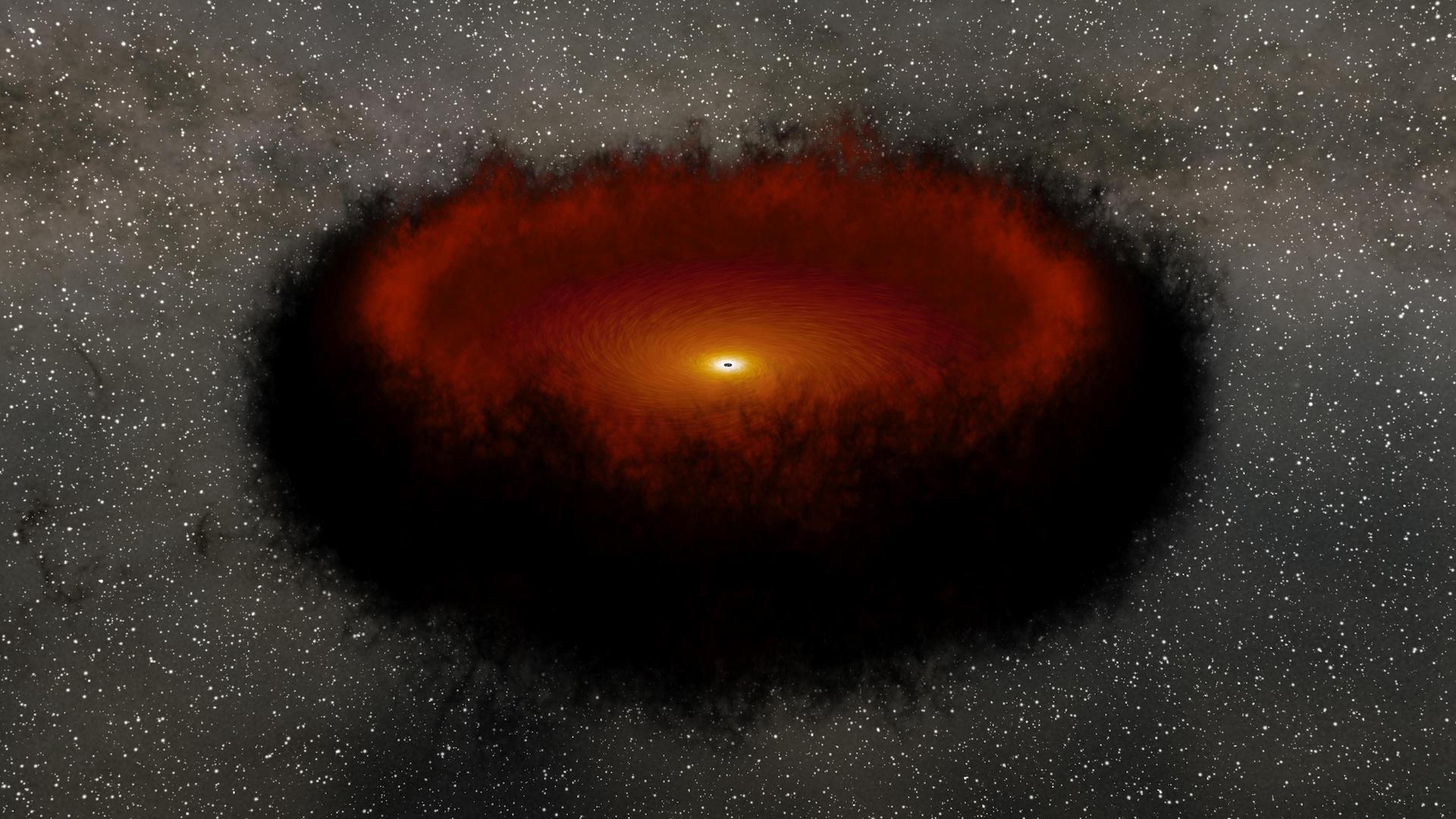

Viscosity is a measure of how much a fluid resists flowing or changing shape — like the difference between pouring water versus honey. In this case, we are talking about the bulk viscosity of the vacuum itself, a ghostly resistance that occurs when space expands.

You may like-

30 models of the universe proved wrong by final data from groundbreaking telescope

30 models of the universe proved wrong by final data from groundbreaking telescope

-

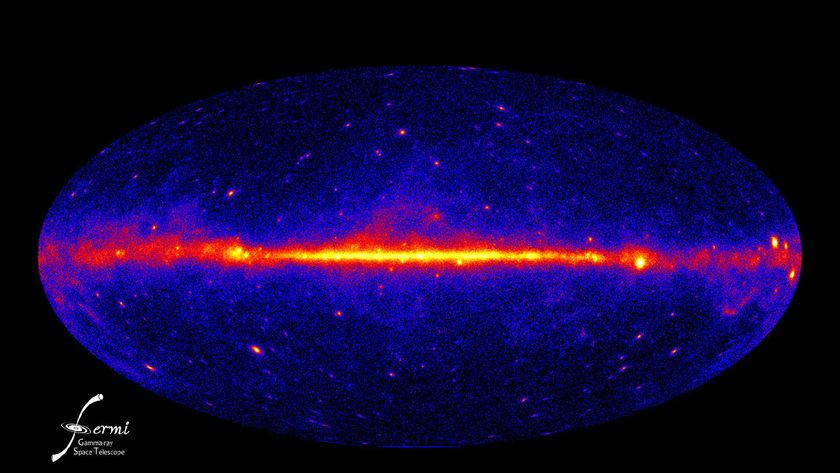

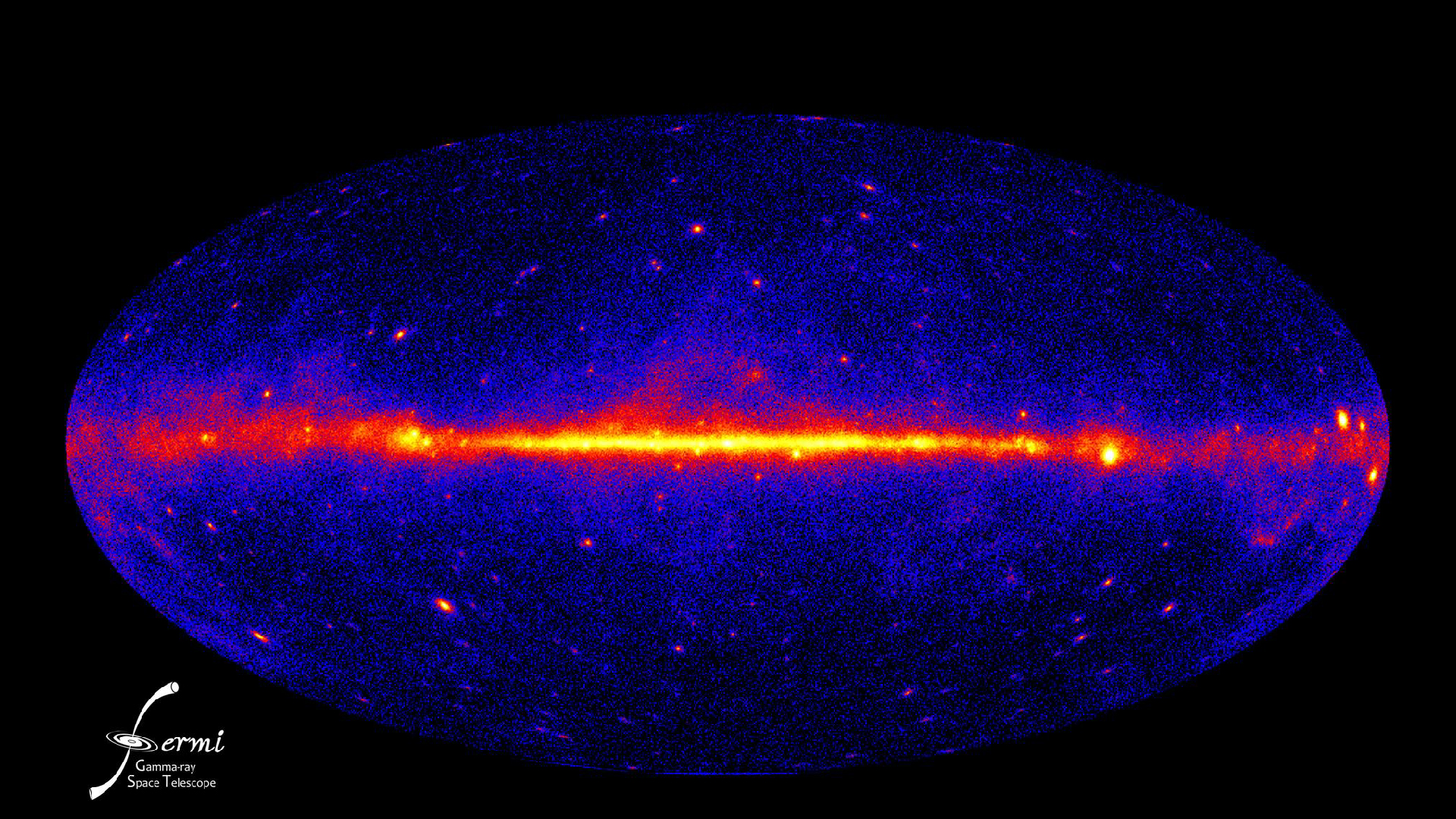

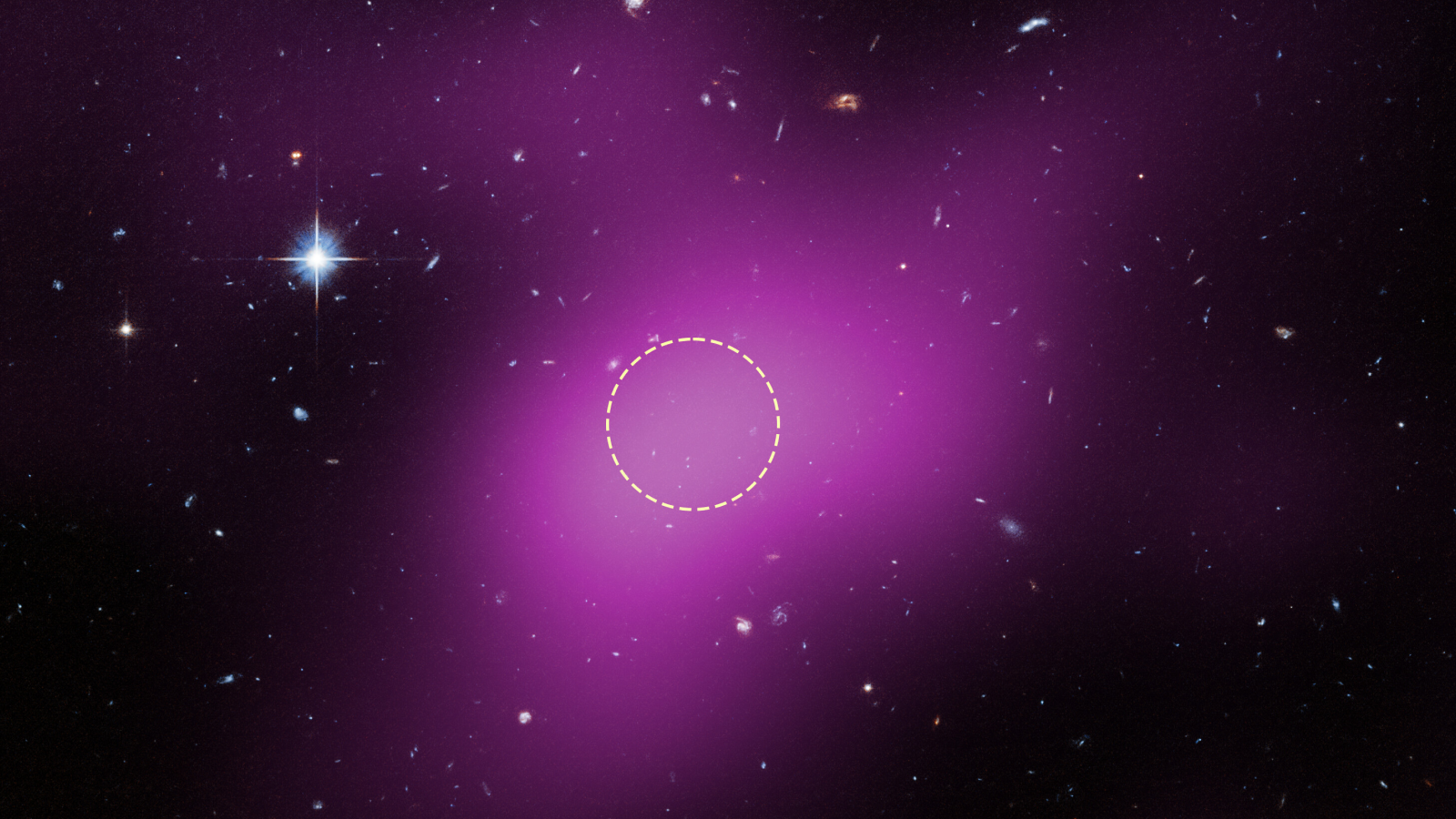

Mysterious glow at the Milky Way's center could reshape a major cosmic theory

Mysterious glow at the Milky Way's center could reshape a major cosmic theory

-

Did a NASA telescope really 'see' dark matter? Strange gamma-rays spark bold claims, but scientists urge caution

Did a NASA telescope really 'see' dark matter? Strange gamma-rays spark bold claims, but scientists urge caution

A constant problem

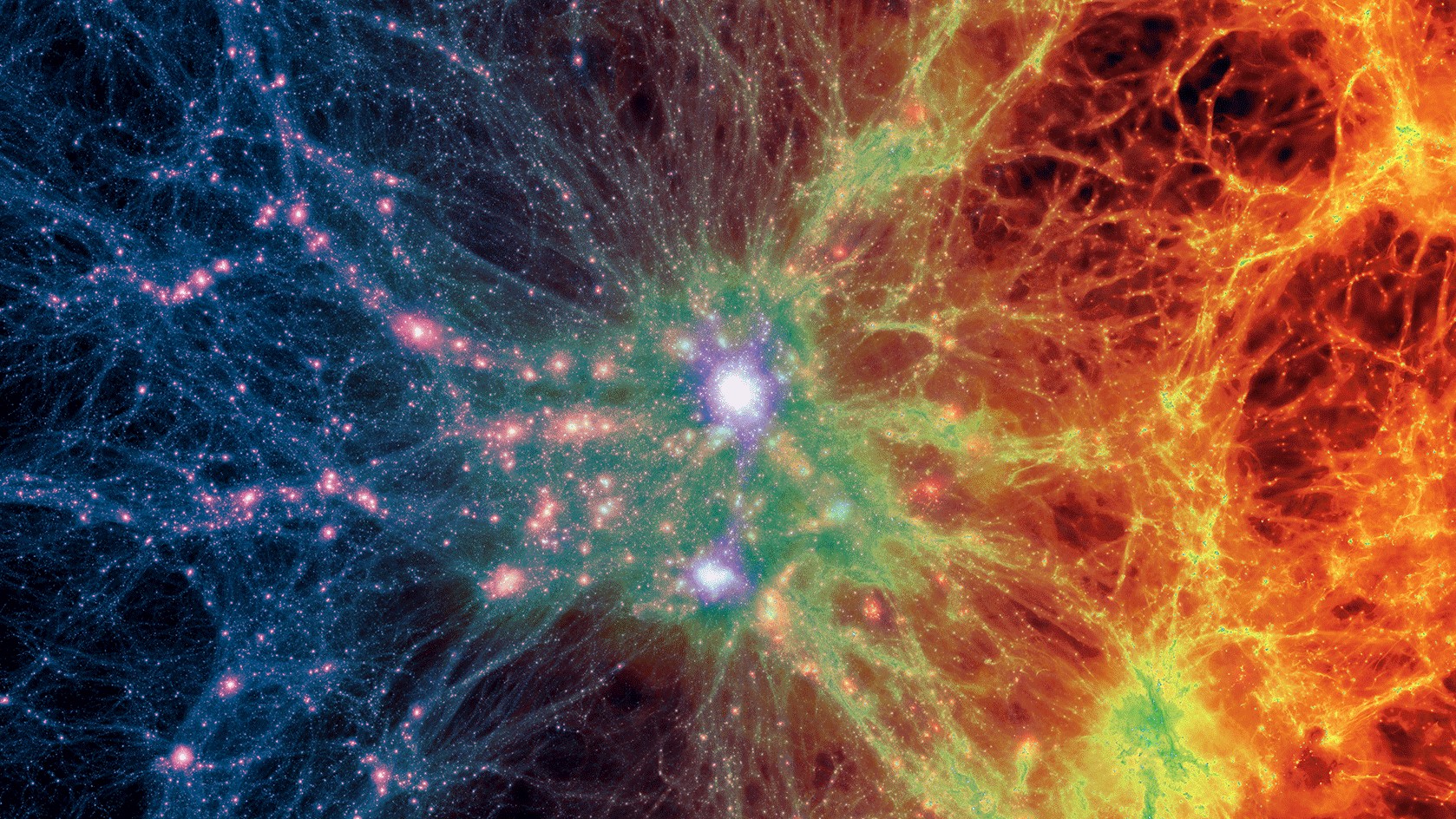

Traditionally, scientists have used a simple model to describe the universe. In this model, known as Lambda-CDM, dark energy — the mysterious force responsible for the accelerating expansion of the universe — is a steady, unchanging background known as the cosmological constant.

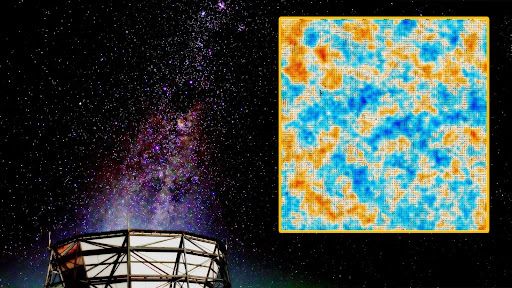

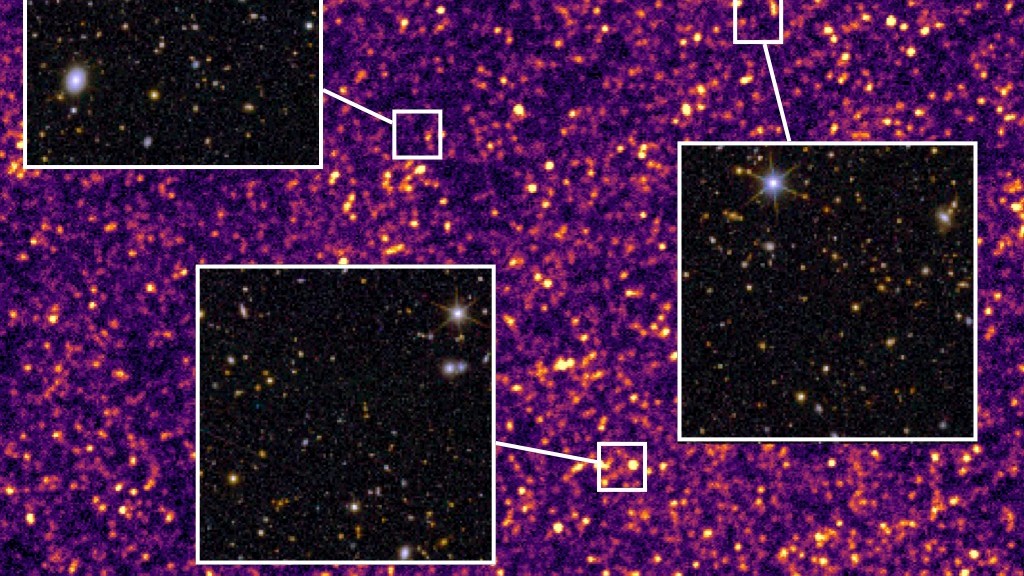

However, data from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), which is mounted on the Mayall Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, released last year hinted that something may be fundamentally wrong with our understanding of dark energy. The new observations showed a slight mismatch between our standard theories and the actual, observed rate at which galaxies are zipping away from us.

To explain this discrepancy, Khan has proposed a model involving spatial "phonons." In solid-state physics, phonons are essentially the collective vibrations of atoms in a crystal. But Khan applied this idea to the fabric of space itself. He suggested that these longitudinal vibrations, which would act as sound waves of the vacuum, could be responsible for a viscous effect that slowed the expansion of the cosmos just enough to match what we see in the sky.

By treating the universe as a viscous fluid, this model introduces a drag on cosmic expansion. As space stretches, these spatial phonons slosh around, creating a pressure that opposes the outward push. In fact, the study shows that this simple, data-based model fits the DESI data with great precision, potentially solving some of the headaches caused by the standard cosmological constant.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.related stories—Scientists may have finally found where the 'missing half' of the universe's matter is hiding

—30 models of the universe proved wrong by final data from groundbreaking cosmology telescope

—Scientists discover smallest galaxy ever seen: 'It's like having a perfectly functional human being that's the size of a grain of rice'

But we should tread lightly — this is merely a guess. Viscous dark energy would be a foundational shift in how we view the vacuum of space, and the hard data from DESI are still being analyzed by the scientific community. We aren't yet sure if this viscosity is a fundamental property of nature or just a sluggish artifact of our current measurements.

So, where do we go from here? The next decade of data from missions like the Euclid space telescope and continued monitoring by DESI will be the ultimate test. We need more observations to see if these ghostly vibrations are truly ruling the cosmos, or if space is as smooth as we once believed.

Paul SutterSocial Links NavigationAstrophysicist

Paul SutterSocial Links NavigationAstrophysicistPaul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at SUNY Stony Brook University and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He regularly appears on TV and podcasts, including "Ask a Spaceman." He is the author of two books, "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space," and is a regular contributor to Space.com, Live Science, and more. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Mysterious glow at the Milky Way's center could reshape a major cosmic theory

Mysterious glow at the Milky Way's center could reshape a major cosmic theory

Did a NASA telescope really 'see' dark matter? Strange gamma-rays spark bold claims, but scientists urge caution

Did a NASA telescope really 'see' dark matter? Strange gamma-rays spark bold claims, but scientists urge caution

Historic search for 'huge missing piece' of the universe reveals new secrets of particle physics

Historic search for 'huge missing piece' of the universe reveals new secrets of particle physics

'Colder and deader from now on': Euclid telescope confirms the universe has already peaked in star formation

'Colder and deader from now on': Euclid telescope confirms the universe has already peaked in star formation

Hubble telescope discovers 'Cloud-9,' a dark and rare 'failed galaxy' that's unlike anything seen before

Hubble telescope discovers 'Cloud-9,' a dark and rare 'failed galaxy' that's unlike anything seen before

'How can all of this be happening?': Scientists spot massive group of ancient galaxies so hot they shouldn't exist

Latest in Dark Energy

'How can all of this be happening?': Scientists spot massive group of ancient galaxies so hot they shouldn't exist

Latest in Dark Energy

'The universe has thrown us a curveball': Largest-ever map of space reveals we might have gotten dark energy totally wrong

'The universe has thrown us a curveball': Largest-ever map of space reveals we might have gotten dark energy totally wrong

Cosmic voids may explain the universe's acceleration without dark energy

Cosmic voids may explain the universe's acceleration without dark energy

'A frankly embarrassing result': We still know hardly anything about 95% of the universe

'A frankly embarrassing result': We still know hardly anything about 95% of the universe

The universe may end in a 'Big Freeze,' holographic model of the universe suggests

The universe may end in a 'Big Freeze,' holographic model of the universe suggests

Huge cosmological mystery could be solved by wormholes, new study argues

Huge cosmological mystery could be solved by wormholes, new study argues

Black hole singularities defy physics. New research could finally do away with them.

Latest in News

Black hole singularities defy physics. New research could finally do away with them.

Latest in News

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

Earth hit by biggest 'solar radiation storm' in 23 years, triggering Northern Lights as far as Southern California

Earth hit by biggest 'solar radiation storm' in 23 years, triggering Northern Lights as far as Southern California

Medieval 'super ship' found wrecked off Denmark is largest vessel of its kind

Medieval 'super ship' found wrecked off Denmark is largest vessel of its kind

Ever watched a pet cow pick up a broom and scratch herself with it? You have now

Ever watched a pet cow pick up a broom and scratch herself with it? You have now

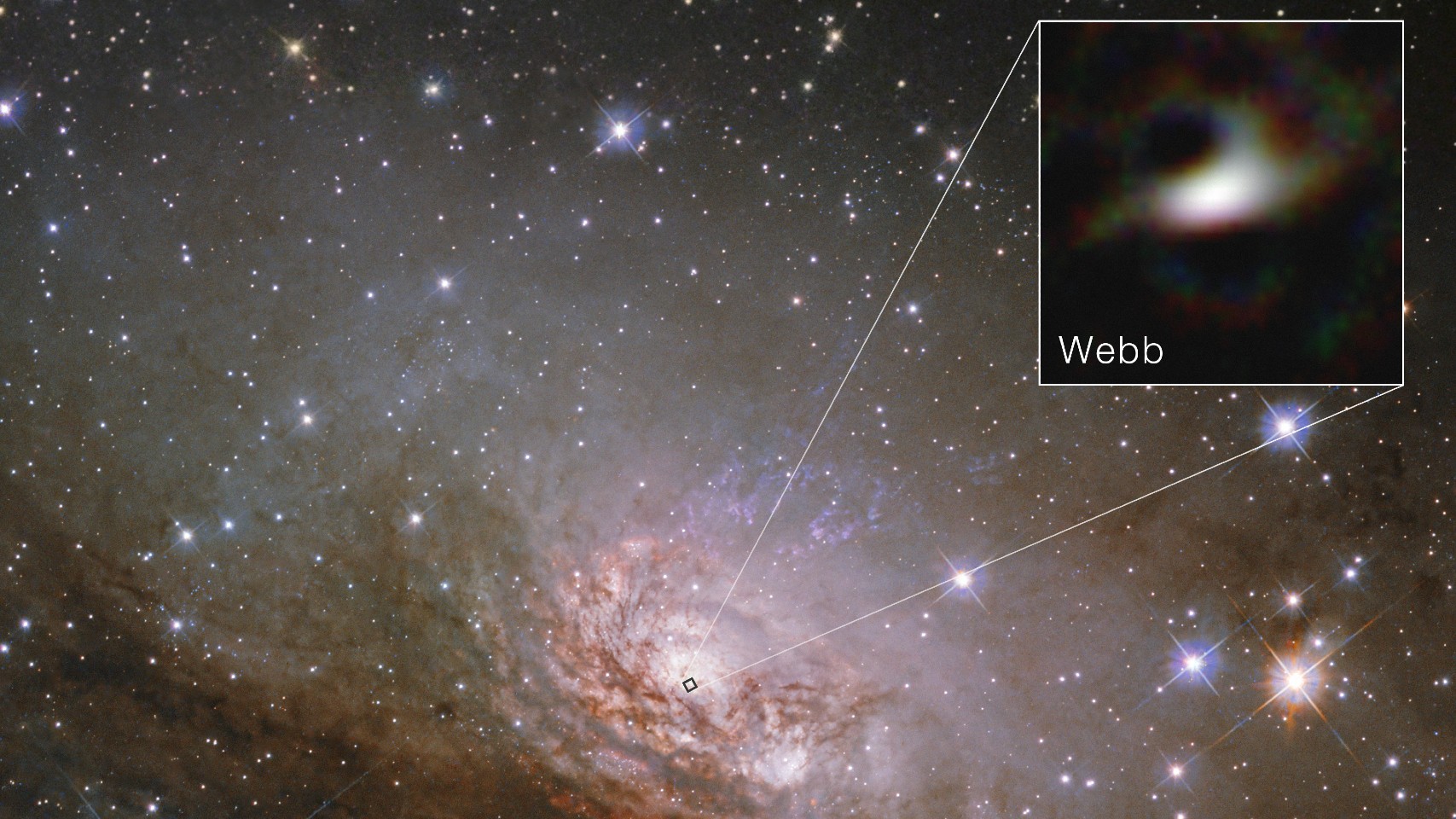

James Webb telescope reveals sharpest-ever look at the edge of a supermassive black hole

James Webb telescope reveals sharpest-ever look at the edge of a supermassive black hole

Why is flu season so bad this year?

LATEST ARTICLES

Why is flu season so bad this year?

LATEST ARTICLES 1Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

1Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints- 2Medieval 'super ship' found wrecked off Denmark is largest vessel of its kind

- 3Suunto Vertical 2 smartwatch review: Beauty and the beast

- 41,700-year-old Roman marching camps discovered in Germany — along with a multitude of artifacts like coins and the remnants of shoes

- 5Giant underwater plumes triggered by 7-story waves at Nazaré captured off Portuguese coast — Earth from space