- Health

- Genetics

New research finds that retinal diseases thought to map one-to-one to genetic mutations are more complicated than that.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

A new study may transform scientists' understanding of inherited blindness, as well as other genetic conditions.

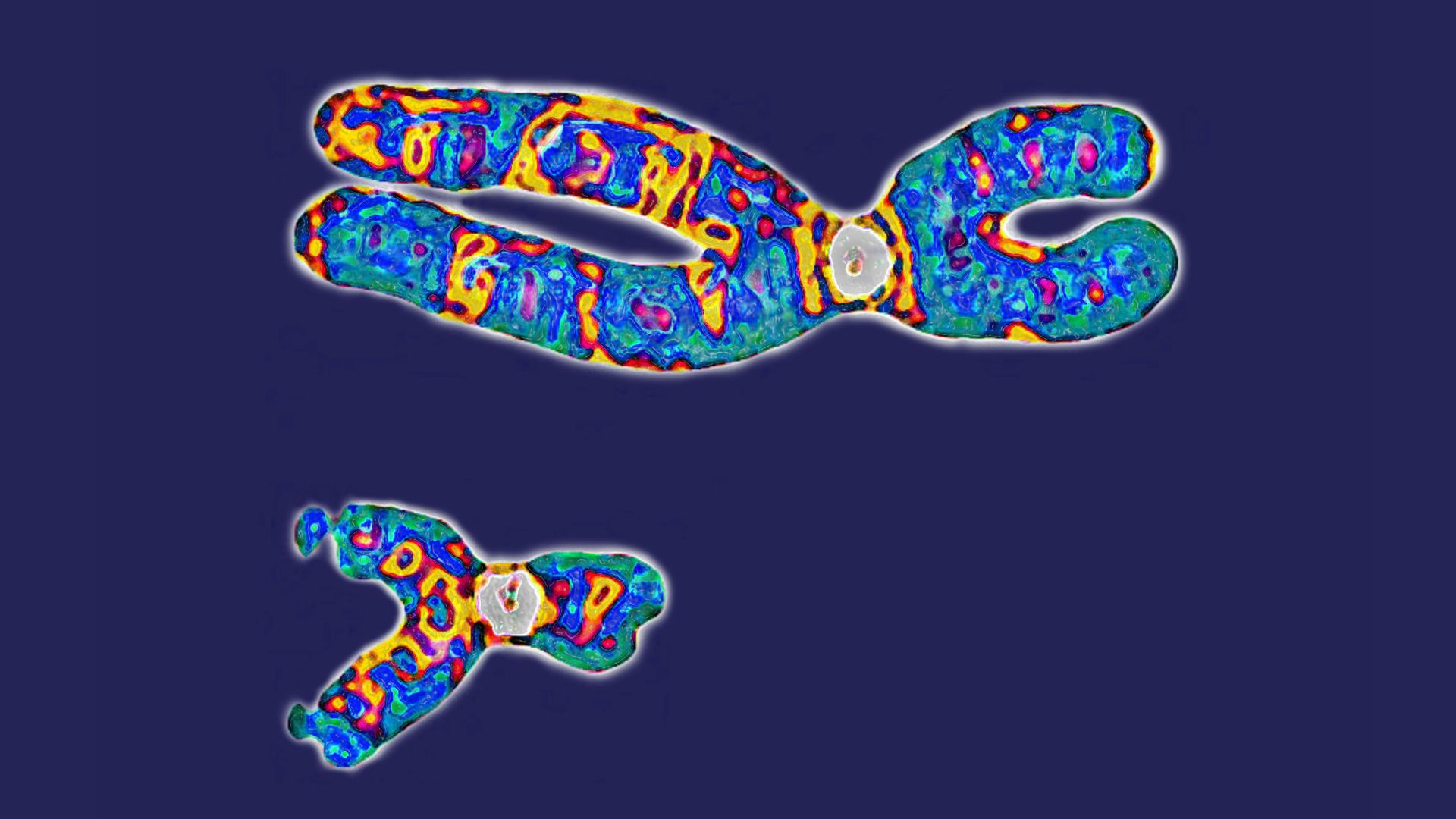

(Image credit: artacet/Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

A new study may transform scientists' understanding of inherited blindness, as well as other genetic conditions.

(Image credit: artacet/Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Genetic variants believed to cause blindness in nearly everyone who carries them actually lead to vision loss less than 30% of the time, new research finds.

The study challenges the concept of Mendelian diseases, or diseases and disorders attributed to a single genetic mutation. The idea is that Mendelian diseases — such as the neurological disease Huntington's and the bleeding disorder hemophilia — are passed down in predictable ways in families, and if a given person carries a disease-causing mutation, they will have it.

You may like-

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

-

5 genetic 'signatures' underpin a range of psychiatric conditions

5 genetic 'signatures' underpin a range of psychiatric conditions

-

Injecting anesthetic into a 'lazy eye' may correct it, early study suggests

Injecting anesthetic into a 'lazy eye' may correct it, early study suggests

"What we suggest is that there is overlap there," senior study author Dr. Eric Pierce, director of the Ocular Genomics Institute at Mass Eye and Ear and an ophthalmologist at Harvard Medical School, told Live Science. In other words, many diseases thought to have simple, Mendelian causes might be a lot more complex than previously thought.

And this doesn't only apply to inherited blindness. Similar results have been found for other genes once thought to be strongly linked to health conditions. A 2023 study on ovarian insufficiency, a condition that causes infertility and early menopause, found that 99.9% of supposedly disease-causing variants were actually present in healthy women. And certain kinds of inherited diabetes also have more complex genetics than previously believed, according to 2022 research.

"We're in an era of discovering a lot more about the complexity of our genomes," said Anna Murray, a geneticist at the University of Exeter who led the ovarian insufficiency research.

Simple or complex?

Pierce and his colleagues focused on inherited retinal disorders (IRDs), a group of diseases that cause significant vision loss, sometimes as early as age 10 but certainly by age 40, said study co-author Dr. Elizabeth Rossin, a vitreoretinal surgeon and scientist in Mass Eye and Ear’s Retina Service and a Harvard ophthalmologist. Researchers have teased out the genetic roots of these diseases by doing genetic testing on affected patients and their families.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.But that method can lead to a problem called ascertainment bias, Pierce said. True, you'll learn that some genetic variants are associated with the disease. But because you're studying only people with the disease and their relatives, you don't get a clear notion of how many people have the same gene variants and don't go blind.

To widen their view, the researchers used data from two large biobanks that contain genetic sequencing data from people, as well as their medical diagnoses and demographic information. One, the All of Us biobank, is a program run by the National Institutes of Health and included nearly 318,000 individuals with both genetic and electronic health record data at the time of the study. The other, the UK Biobank, is comparatively less diverse but contains data from 500,000 individuals, including about 100,000 with images of their retinas submitted to the database.

The researchers picked the 167 genetic variants thought to have the strongest causal link to IRDs and searched for them in the All of Us database. They then used the health record data to see if the people with the variants had vision loss. To their surprise, depending on which diagnostic codes they used, only 9.4% to 28.1% of people with the variants had any indication of a retinal disorder or vision problems.

You may like-

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

-

5 genetic 'signatures' underpin a range of psychiatric conditions

5 genetic 'signatures' underpin a range of psychiatric conditions

-

Injecting anesthetic into a 'lazy eye' may correct it, early study suggests

Injecting anesthetic into a 'lazy eye' may correct it, early study suggests

"You would expect, given what we know about these diseases, that nearly 100% of the people would have blindness," Rossin told Live Science. "But it was far fewer than that."

To validate their findings, the researchers turned to the UK Biobank, this time using the included retinal imagery to seek out evidence of IRDs themselves. They found that only between 16.1% and 27.9% carriers of the gene variants had indications of possible retinal disease.

People who were older who carried these retinal disease genes weren't any likelier to have gone blind. And there was no other evidence that their results were because they were catching people who might later lose their vision. Instead, Pierce says, it seems that the complexity of these presumed Mendelian diseases has been underestimated.

"The mutation we used to think caused disease 100% of the time doesn't exist in isolation," he said. Instead, people carry tens or hundreds of thousands of other genes, some of which may protect against retinal disease, he added.

New avenues for treatment

In theory, those protective gene variants could lead to ways to treat these retinal disorders.

"It's going to take a lot of data in order to find these types of low-effect variants," Pierce said. "There are likely many of them, each contributing a little bit to the protection against disease."

There are good reasons to study the genes of patients with particular disorders, Murray said. For instance, finding genes associated with a condition — even if they don't always cause it — can help researchers pinpoint the biology underlying the disease. In ovarian insufficiency, these kinds of patient-centered studies have shown that genes associated with DNA repair are important for the disorder. But such studies should still be taken with a grain of salt.

RELATED STORIES—CRISPR can treat common form of inherited blindness, early data hint

—New cells discovered in eye could help restore vision, scientists say

—Woman's sudden blindness in 1 eye revealed hidden lung cancer

"It is only now that we have the ability to look at the granular detail of the genetic sequence in hundreds of thousands of people," she said. To learn more, these databases need to become more diverse, she added. And at the same time, she added, biomedical researchers need better lab models of diseases in which to test certain gene mutations and their effects.

"There are likely some [diseases] where it really is a one-to-one correspondence," Pierce said. "But my prediction would be [that] the majority of these disorders are going to share this new complexity."

The new findings appeared Jan. 8 in the American Journal of Human Genetics.

Editor's note: This story was updated on Jan. 16, 2026, to add mention of Dr. Eric Pierce's and Dr. Elizabeth Rossin's affiliations with Mass Eye and Ear, where the work was conducted.

Stephanie PappasSocial Links NavigationLive Science Contributor

Stephanie PappasSocial Links NavigationLive Science ContributorStephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

5 genetic 'signatures' underpin a range of psychiatric conditions

5 genetic 'signatures' underpin a range of psychiatric conditions

Injecting anesthetic into a 'lazy eye' may correct it, early study suggests

Injecting anesthetic into a 'lazy eye' may correct it, early study suggests

'More Neanderthal than human': How DNA from our long-lost ancestors affects our health today

'More Neanderthal than human': How DNA from our long-lost ancestors affects our health today

From gene therapy breakthroughs to preventable disease outbreaks: The health trends that will shape 2026

From gene therapy breakthroughs to preventable disease outbreaks: The health trends that will shape 2026

DNA from ancient viral infections helps embryos develop, mouse study reveals

Latest in Genetics

DNA from ancient viral infections helps embryos develop, mouse study reveals

Latest in Genetics

This is SPARDA: A self-destruct, self-defense system in bacteria that could be a new biotech tool

This is SPARDA: A self-destruct, self-defense system in bacteria that could be a new biotech tool

DNA from ancient viral infections helps embryos develop, mouse study reveals

DNA from ancient viral infections helps embryos develop, mouse study reveals

Leonardo da Vinci's DNA may be embedded in his art — and scientists think they've managed to extract some

Leonardo da Vinci's DNA may be embedded in his art — and scientists think they've managed to extract some

'More Neanderthal than human': How DNA from our long-lost ancestors affects our health today

'More Neanderthal than human': How DNA from our long-lost ancestors affects our health today

5 genetic 'signatures' underpin a range of psychiatric conditions

5 genetic 'signatures' underpin a range of psychiatric conditions

Woman had her twin brother's XY chromosomes — but only in her blood

Latest in News

Woman had her twin brother's XY chromosomes — but only in her blood

Latest in News

Scientists see monster black hole 'reborn' after 100 million years of rest

Scientists see monster black hole 'reborn' after 100 million years of rest

Tiny improvements in sleep, nutrition and exercise could significantly extend lifespan, study suggests

Tiny improvements in sleep, nutrition and exercise could significantly extend lifespan, study suggests

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

Earth hit by biggest 'solar radiation storm' in 23 years, triggering Northern Lights as far as Southern California

Earth hit by biggest 'solar radiation storm' in 23 years, triggering Northern Lights as far as Southern California

Medieval 'super ship' found wrecked off Denmark is largest vessel of its kind

Medieval 'super ship' found wrecked off Denmark is largest vessel of its kind

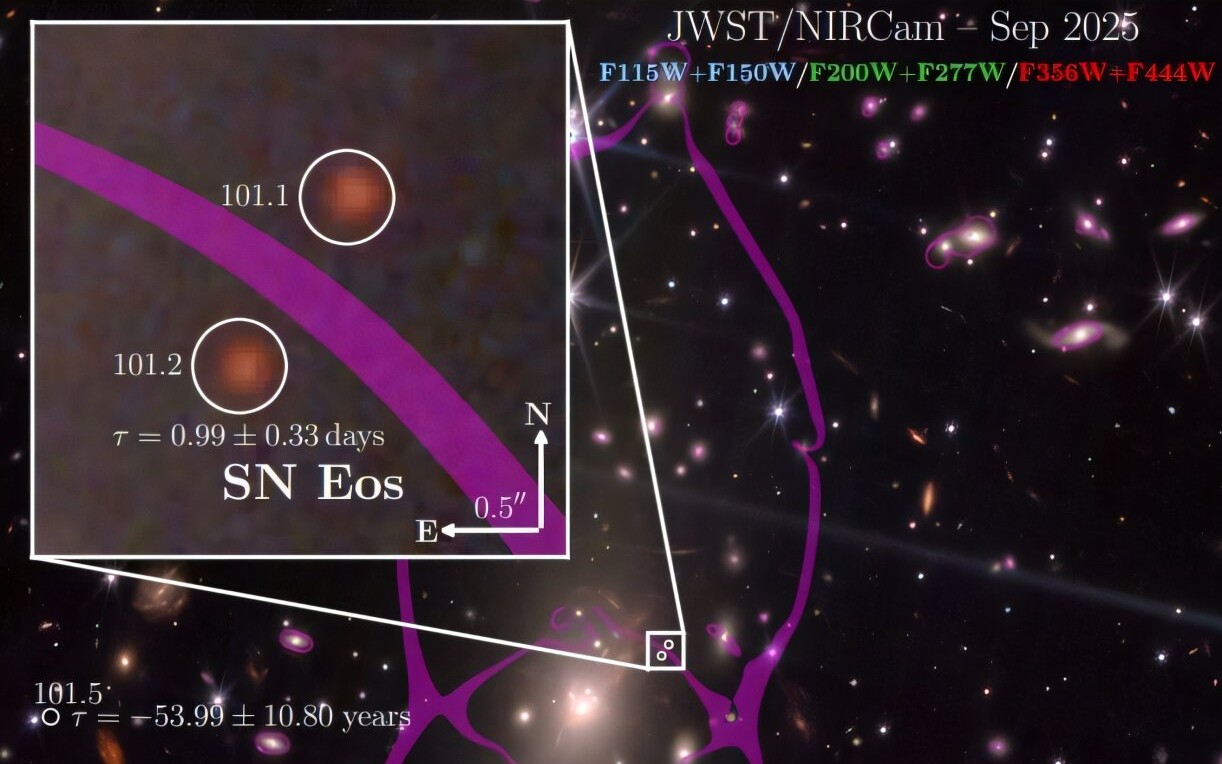

James Webb telescope discovers earliest Type II supernova in the known universe

LATEST ARTICLES

James Webb telescope discovers earliest Type II supernova in the known universe

LATEST ARTICLES 1Tiny improvements in sleep, nutrition and exercise could significantly extend lifespan, study suggests

1Tiny improvements in sleep, nutrition and exercise could significantly extend lifespan, study suggests- 2James Webb telescope spies rare 'goddess of dawn' supernova from the early universe

- 3Earth hit by biggest 'solar radiation storm' in 23 years, triggering Northern Lights as far as Southern California

- 4Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

- 5Medieval 'super ship' found wrecked off Denmark is largest vessel of its kind