- Archaeology

How did Romans invest their wealth in ancient times?

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

A priestly crown featuring Helios from the first century A.D. found in what is now Turkey.

(Image credit: I, Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Share

Share by:

A priestly crown featuring Helios from the first century A.D. found in what is now Turkey.

(Image credit: I, Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

"All I want is an income of 20,000 sesterces from secure investments", proclaims a character in a poem by Juvenal (first to second century A.D.), the Roman poet.

Today, 20,000 sesterces would be equivalent to about [Australian] $300,000 in interest from investments. Anyone would be very happy with this much passive annual income.

A lofty house with hidden silver

In ancient Greek and Roman times, there was no stock market where you could buy and trade shares in a company.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.If you wanted to invest your cash, one of the more popular options was to obtain gold or silver.

People did this to protect against currency fluctuations and inflation. They usually kept the metals either in bullion form or in the form of ware like jewelry. Storing these items could be risky and prone to theft.

The Roman poet Virgil (70 to 19 B.C.) describes the estate of a wealthy person that included "a lofty house, where talents of silver lie deeply hidden" alongside "weights of gold in bullion and in ware".

You may like-

1,800-year-old 'piggy banks' full of Roman-era coins unearthed in French village

1,800-year-old 'piggy banks' full of Roman-era coins unearthed in French village

-

2,000-year-old gold ring holds clue about lavish cremation burial unearthed in France

2,000-year-old gold ring holds clue about lavish cremation burial unearthed in France

-

New discoveries at Hadrian's Wall are changing the picture of what life was like on the border of the Roman Empire

New discoveries at Hadrian's Wall are changing the picture of what life was like on the border of the Roman Empire

A talent was the largest unit of currency measurement in ancient Greece and Rome, equivalent to about 25 kg [55 pounds] of weighed silver.

Usually the metals were stored in a special vault or security cupboard.

The Roman writer Cicero (106 to 43 B.C.) recalls how a wealthy lady named Clodia would take gold (perhaps bars or ingots or plates) out of a security cupboard when she wished to lend money to someone. The gold could then be exchanged for coinage.

Market booms — and busts

The price of these metals could, however, occasionally be subject to unpredictable fluctuations and crashes in price, though less often than currency.

The Greek historian Polybius (c. 200 to 118 B.C.) says that when a new gold vein was discovered in Aquileia, Italy, only two feet deep, it caused a gold rush. The new material flooded the market too quickly and "the price of gold throughout Italy at once fell by one-third" after only two months. To stabilize the gold price, mining in the area was quickly monopolized and regulated.

When people wanted to trade precious metals, they would sell them by weight. If the gold or silver or bronze had been worked into jewelry or other objects, this could be melted down and turned into bullion.

People must have delighted in owning these precious metals.

The Athenian writer Xenophon (c. 430 to 350 B.C.) gives a clue about the mindset of ancient silver investors:

Silver is not like furniture, of which a man never buys more once he has got enough for his house. No one ever yet possessed so much silver as to want no more; if a man finds himself with a huge amount of it, he takes as much pleasure in burying the surplus as in using it.

A number of Roman wills reveal people leaving their heirs silver and gold in the form of bars, plates or ingots.

Commodities that could not be 'ruined by Jupiter'

Aside from metals, agricultural commodities were also very popular, especially grain, olive oil, and wine.

To profit from agricultural commodities, people bought farmland and traded the commodities on the market.

The Roman statesman Cato thought putting money into the production of essential goods was the safest investment. He said these things "could not be ruined by Jupiter" – in other words, they were resistant to unpredictable movements in the economy.

Whereas precious metals were a store of wealth, they generated no income unless they were sold. But a diversified portfolio of agricultural commodities guaranteed a permanent income.

People also invested and traded in precious goods, like artworks.

When the Romans sacked the city of Corinth in 146 B.C., they stole the city's collection of famous artwork, and later sold the masterpieces for huge sums of money at auction in order to bring profit for the Roman state.

At this auction, the King of Pergamon, Attalus II (220 to 138 B.C.), bought one of the paintings, by the master artist Aristeides of Thebes (fourth century B.C.), for the incredible sum of 100 talents (about 2,500 kg [5,500 pounds] of silver).

Eccentric emperors

Political instability or uncertainty sometimes raised the price of these metals.

The Greek historian Appian (secondnd century A.D.) records how during the Roman civil war in 32. to 30 B.C.:

the price of all commodities had risen, and the Romans ascribed the cause of this to the quarreling of the leaders whom they cursed.

Eccentric emperors might also impose new taxes or charges on commodities, or try to manipulate the market.

RELATED STORIES—Ancient Egyptian valley temple excavated — and it's connected to a massive upper temple dedicated to the sun god, Ra

—Pompeii victims were wearing woolen cloaks in August when they died — but experts are split on what that means

—1,100-year-old Viking hoard reveals raiding wealthy only 'part of the picture' — they traded with the Middle East too

The Roman historian Suetonius (c. A.D. 69 to 122 ) tells us the emperor Caligula (A.D. 12 to 41) "levied new and unheard of taxes […] and there was no class of commodities or men on which he did not impose some form of tariff."

Another emperor, Vespasian (A.D. 17 to 79), went so far as to "buy up certain commodities merely in order to distribute them at profit", says Suetonius.

Clearly, investing in commodities 2,000 years ago could help build personal wealth — but also involved some risk, just like today.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Konstantine PanegyresMcKenzie Postdoctoral Fellow, researching Greco-Roman antiquity, The University of Melbourne

Konstantine PanegyresMcKenzie Postdoctoral Fellow, researching Greco-Roman antiquity, The University of MelbourneOriginally from Western Australia, I received my doctorate from the University of Oxford in 2022 as a Clarendon Scholar. My current work is about health in the ancient world, the subject of an upcoming book. I am also involved in the editing of unpublished papyri from the Greco-Roman period.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more 1,800-year-old 'piggy banks' full of Roman-era coins unearthed in French village

1,800-year-old 'piggy banks' full of Roman-era coins unearthed in French village

2,000-year-old gold ring holds clue about lavish cremation burial unearthed in France

2,000-year-old gold ring holds clue about lavish cremation burial unearthed in France

New discoveries at Hadrian's Wall are changing the picture of what life was like on the border of the Roman Empire

New discoveries at Hadrian's Wall are changing the picture of what life was like on the border of the Roman Empire

2,300-year-old Celtic gold coins found in Swiss bog

2,300-year-old Celtic gold coins found in Swiss bog

'This has re-written our understanding of Roman concrete manufacture': Abandoned Pompeii worksite reveal how self-healing concrete was made

'This has re-written our understanding of Roman concrete manufacture': Abandoned Pompeii worksite reveal how self-healing concrete was made

Pectoral with coins: 'One of the most intricate pieces of gold jewelry to survive from the mid-sixth century'

Latest in Archaeology

Pectoral with coins: 'One of the most intricate pieces of gold jewelry to survive from the mid-sixth century'

Latest in Archaeology

Medieval 'super ship' found wrecked off Denmark is largest vessel of its kind

Medieval 'super ship' found wrecked off Denmark is largest vessel of its kind

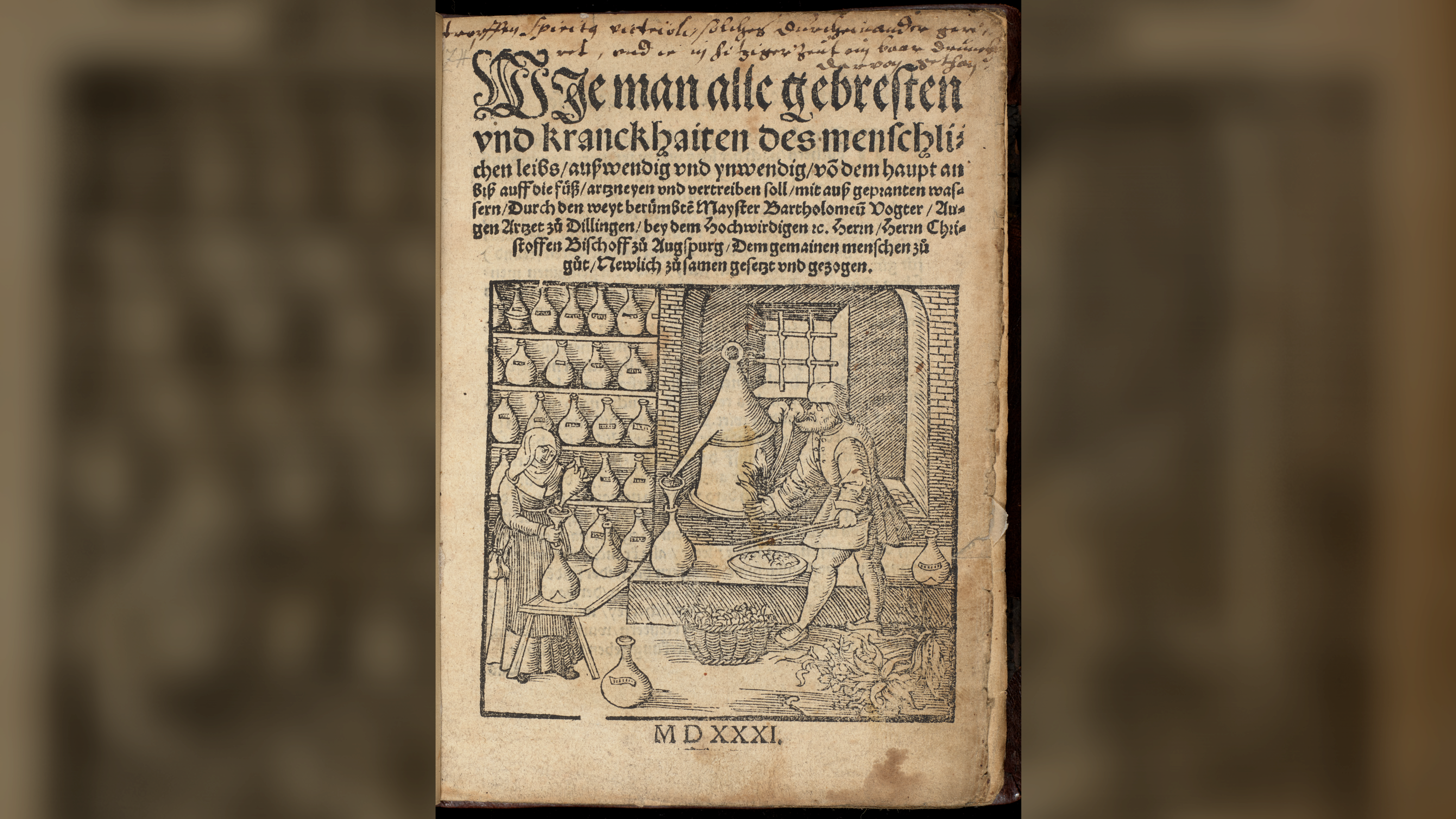

Remnants of spills on Renaissance-era textbook reveal recipes for 'curing' ailments with lizard heads and human feces

Remnants of spills on Renaissance-era textbook reveal recipes for 'curing' ailments with lizard heads and human feces

Romans regularly soaked in filthy, lead-contaminated bath water, Pompeii study finds

Romans regularly soaked in filthy, lead-contaminated bath water, Pompeii study finds

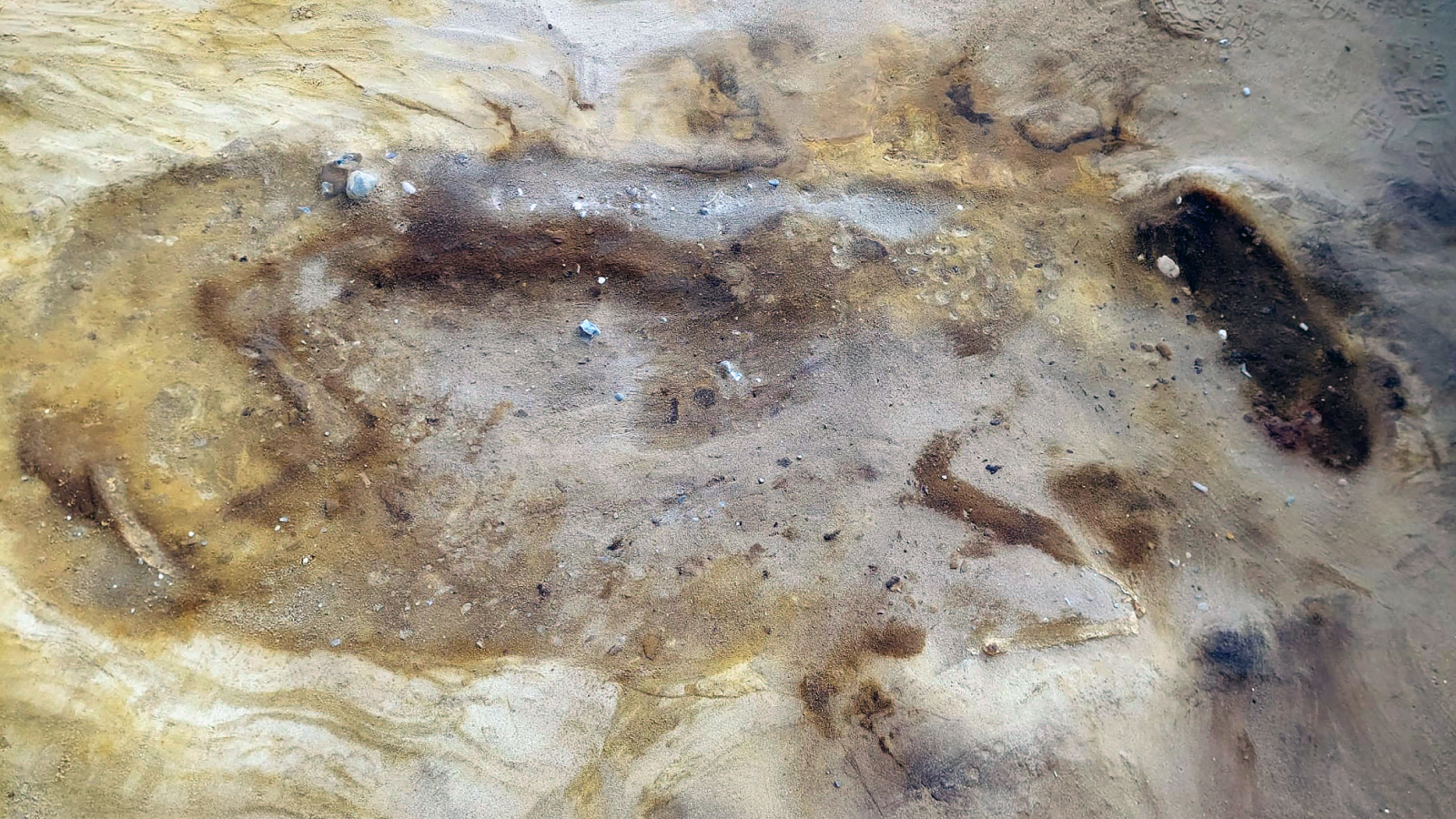

Eerie 'sand burials' of elite Anglo-Saxons and their 'sacrificed' horse discovered near UK nuclear power plant

Eerie 'sand burials' of elite Anglo-Saxons and their 'sacrificed' horse discovered near UK nuclear power plant

Nefertiti's tomb close to discovery, famed archaeologist Zahi Hawaas claims in new documentary

Nefertiti's tomb close to discovery, famed archaeologist Zahi Hawaas claims in new documentary

1,700-year-old Roman marching camps discovered in Germany — along with a multitude of artifacts like coins and the remnants of shoes

Latest in News

1,700-year-old Roman marching camps discovered in Germany — along with a multitude of artifacts like coins and the remnants of shoes

Latest in News

Ever watched a pet cow pick up a broom and scratch herself with it? You have now

Ever watched a pet cow pick up a broom and scratch herself with it? You have now

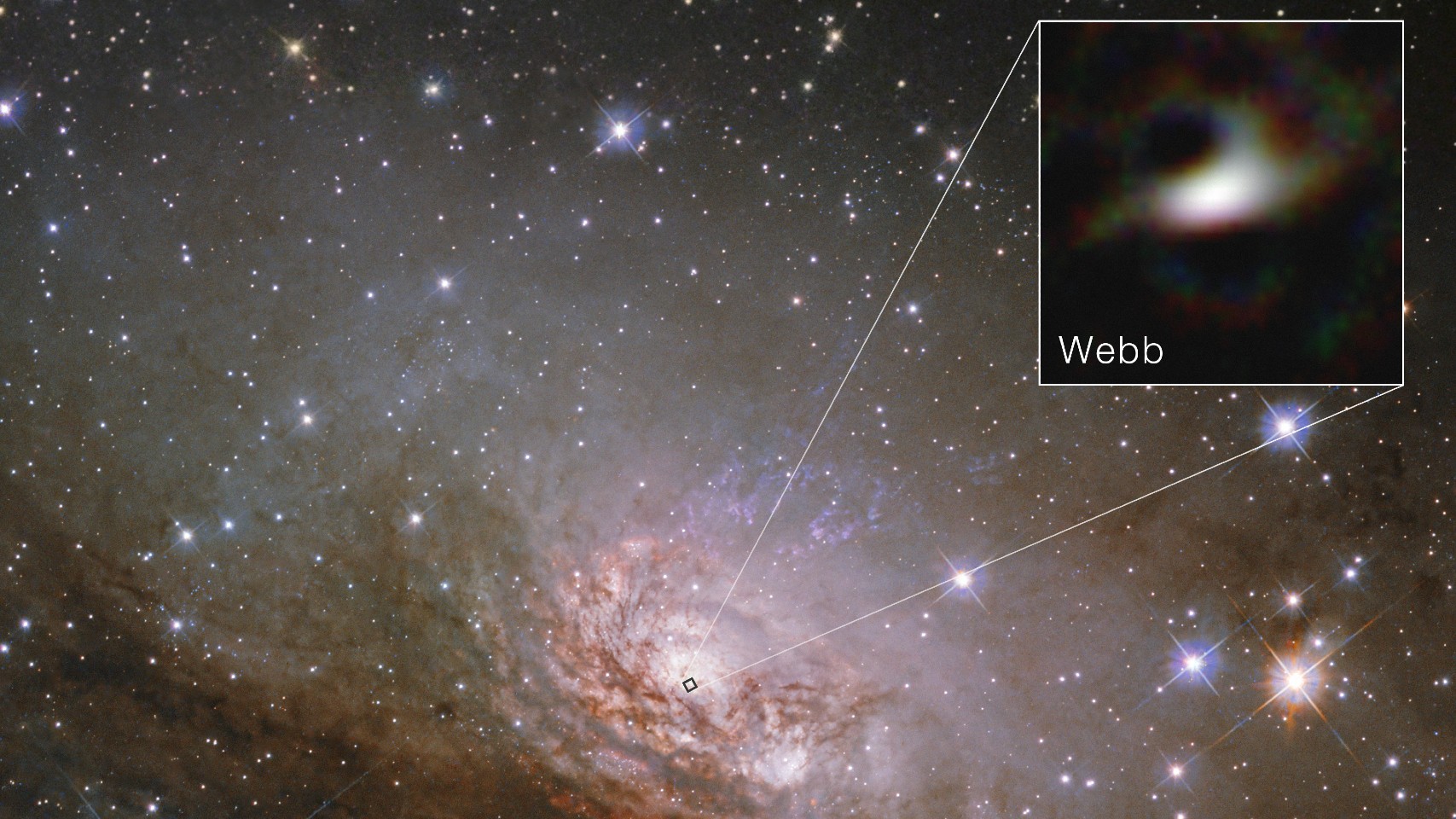

James Webb telescope reveals sharpest-ever look at the edge of a supermassive black hole

James Webb telescope reveals sharpest-ever look at the edge of a supermassive black hole

Why is flu season so bad this year?

Why is flu season so bad this year?

Strange discovery offers 'missing link' in planet formation

Strange discovery offers 'missing link' in planet formation

Watch NASA roll its historic Artemis II moon rocket to the launch pad this weekend

Watch NASA roll its historic Artemis II moon rocket to the launch pad this weekend

Astronomers confirm earliest Milky Way-like galaxy in the universe, just 2 billion years after the Big Bang

LATEST ARTICLES

Astronomers confirm earliest Milky Way-like galaxy in the universe, just 2 billion years after the Big Bang

LATEST ARTICLES 1Suunto Vertical 2 smartwatch review: Beauty and the beast

1Suunto Vertical 2 smartwatch review: Beauty and the beast- 21,700-year-old Roman marching camps discovered in Germany — along with a multitude of artifacts like coins and the remnants of shoes

- 3Giant underwater plumes triggered by 7-story waves at Nazaré captured off Portuguese coast

- 4Indigenous TikTok star 'Bush Legend' is actually AI-generated, leading to accusations of 'digital blackface'

- 5Ever watched a pet cow pick up a broom and scratch herself with it? You have now