- Archaeology

- Romans

A new study shows that organic residues from a Roman-era glass medicinal vial came from human feces.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

Researchers sampled the brownish flakes from inside the Roman glass vial.

(Image credit: Cenker Atila)

Share

Share by:

Researchers sampled the brownish flakes from inside the Roman glass vial.

(Image credit: Cenker Atila)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Dark-brown flakes discovered inside a 1,900-year-old Roman glass vial are the first direct evidence for the use of human feces for medicinal purposes, a new chemical analysis reveals. The feces were mixed with thyme to mask the smell, and the concoction may have been used to treat inflammation or infection.

"While working in the storage rooms of the Bergama Museum, I noticed that some glass vessels contained residues," Cenker Atila, an archaeologist at Sivas Cumhuriyet University in Turkey, told Live Science in an email. "Residues were found in a total of seven different vessels, but only one yielded conclusive results."

You may like-

Remnants of spills on Renaissance-era textbook reveal recipes for 'curing' ailments with lizard heads and human feces

Remnants of spills on Renaissance-era textbook reveal recipes for 'curing' ailments with lizard heads and human feces

-

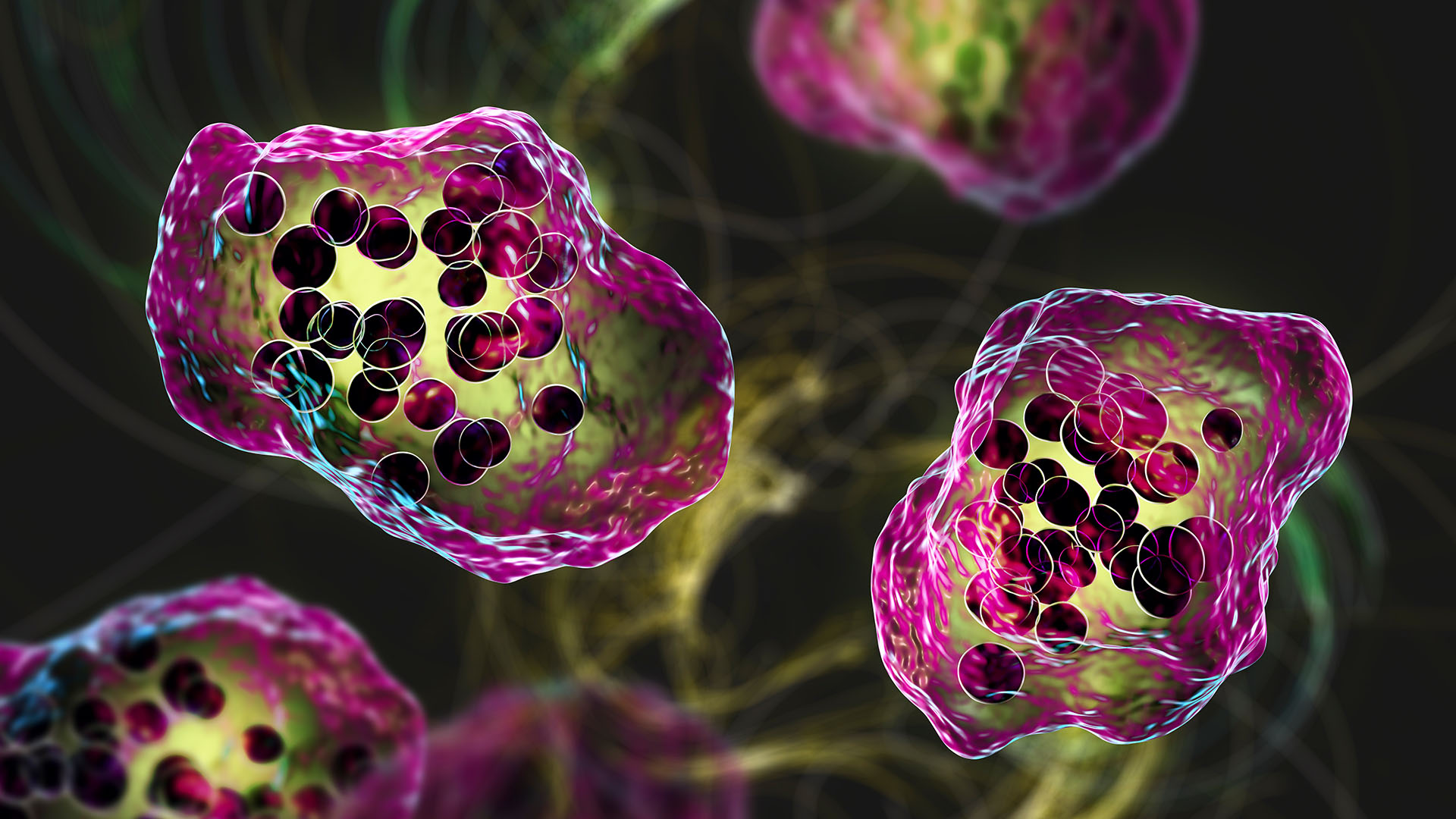

Diarrhea and stomachaches plagued Roman soldiers stationed at Hadrian's Wall, discovery of microscopic parasites finds

Diarrhea and stomachaches plagued Roman soldiers stationed at Hadrian's Wall, discovery of microscopic parasites finds

-

Romans regularly soaked in filthy, lead-contaminated bath water, Pompeii study finds

Romans regularly soaked in filthy, lead-contaminated bath water, Pompeii study finds

"When we opened the unguentarium, there was no bad smell," Atila said. During its stay in storage, however, "the residue inside it was overlooked. I noticed it and immediately initiated the analysis process."

The researchers used gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to identify the organic compounds in the dark-brown residue they had scraped from inside the glass unguentarium. Two of the identified compounds — coprostanol and 24-ethylcoprostanol — are typically found in the digestive tracts of animals that metabolize cholesterol.

"The consistent identification of stanols — validated fecal biomarkers — strongly suggests that the Roman unguentarium originally contained fecal material," the researchers wrote in the study. Although they could not conclusively determine the origin of the feces, the researchers noted that the ratio of coprostanol to 24-ethylcoprostanol suggests it was human.

Another major discovery in the residue was carvacrol, an aromatic organic compound present in essential oils made from certain herbs.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over."In this sample, we identified human feces mixed with thyme," Atila said. "Because we are well-acquainted with ancient textual sources, we immediately recognized this as a medicinal preparation used by the famous Roman physician Galen."

During the second and third centuries, Pergamon was known as a major center for Roman medicine, thanks to the physician and anatomist Galen of Pergamon, whose ideas would come to dominate Western medical science for centuries.

RELATED STORIES—What did ancient Rome smell like? BO, rotting corpses and raw sewage for starters ...

—Remnants of spills on Renaissance-era textbook reveal recipes for 'curing' ailments with lizard heads and human feces

—Romans regularly soaked in filthy, lead-contaminated bath water, Pompeii study finds

There were several popular feces-based remedies in Roman medicine that were meant to treat conditions ranging from inflammation and infection to reproductive disorders, the researchers wrote. In one example, Galen mentioned the therapeutic value of the feces of a child who had eaten legumes, bread and wine. But because ancient physicians knew their patients would reject foul-smelling medicines, they often advocated for masking them with aromatic herbs, wine or vinegar.

"This study provides the first direct chemical evidence for the medicinal use of fecal matter in Greco-Roman antiquity," the researchers wrote, as well as direct evidence that the stench of the excrement was masked with strong-smelling herbs. "These findings closely align with formulations described by Galen and other classical authors, suggesting that such remedies were materially enacted, not merely textually theorized."

Article SourcesAtila, C., Demirbolat, İ., & Çelebi, R. B. (2026). Feces, fragrance and medicine chemical evidence of ancient therapeutics in a Roman unguentarium. Journal of Archaeological Science Reports, 70, 105589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2026.105589

Roman emperor quiz: Test your knowledge on the rulers of the ancient empire

Kristina KillgroveSocial Links NavigationStaff writer

Kristina KillgroveSocial Links NavigationStaff writerKristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Diarrhea and stomachaches plagued Roman soldiers stationed at Hadrian's Wall, discovery of microscopic parasites finds

Diarrhea and stomachaches plagued Roman soldiers stationed at Hadrian's Wall, discovery of microscopic parasites finds

'They had not been seen ever before': Romans made liquid gypsum paste and smeared it over the dead before burial, leaving fingerprints behind, new research finds

'They had not been seen ever before': Romans made liquid gypsum paste and smeared it over the dead before burial, leaving fingerprints behind, new research finds

Archaeologists discover decapitated head the Romans used as a warning to the Celts

Archaeologists discover decapitated head the Romans used as a warning to the Celts

2,000-year-old gold ring holds clue about lavish cremation burial unearthed in France

2,000-year-old gold ring holds clue about lavish cremation burial unearthed in France

French archaeologists uncover 'vast Roman burial area' with cremation graves 'fed' by liquid offerings

French archaeologists uncover 'vast Roman burial area' with cremation graves 'fed' by liquid offerings

1,800-year-old 'piggy banks' full of Roman-era coins unearthed in French village

Latest in Romans

1,800-year-old 'piggy banks' full of Roman-era coins unearthed in French village

Latest in Romans

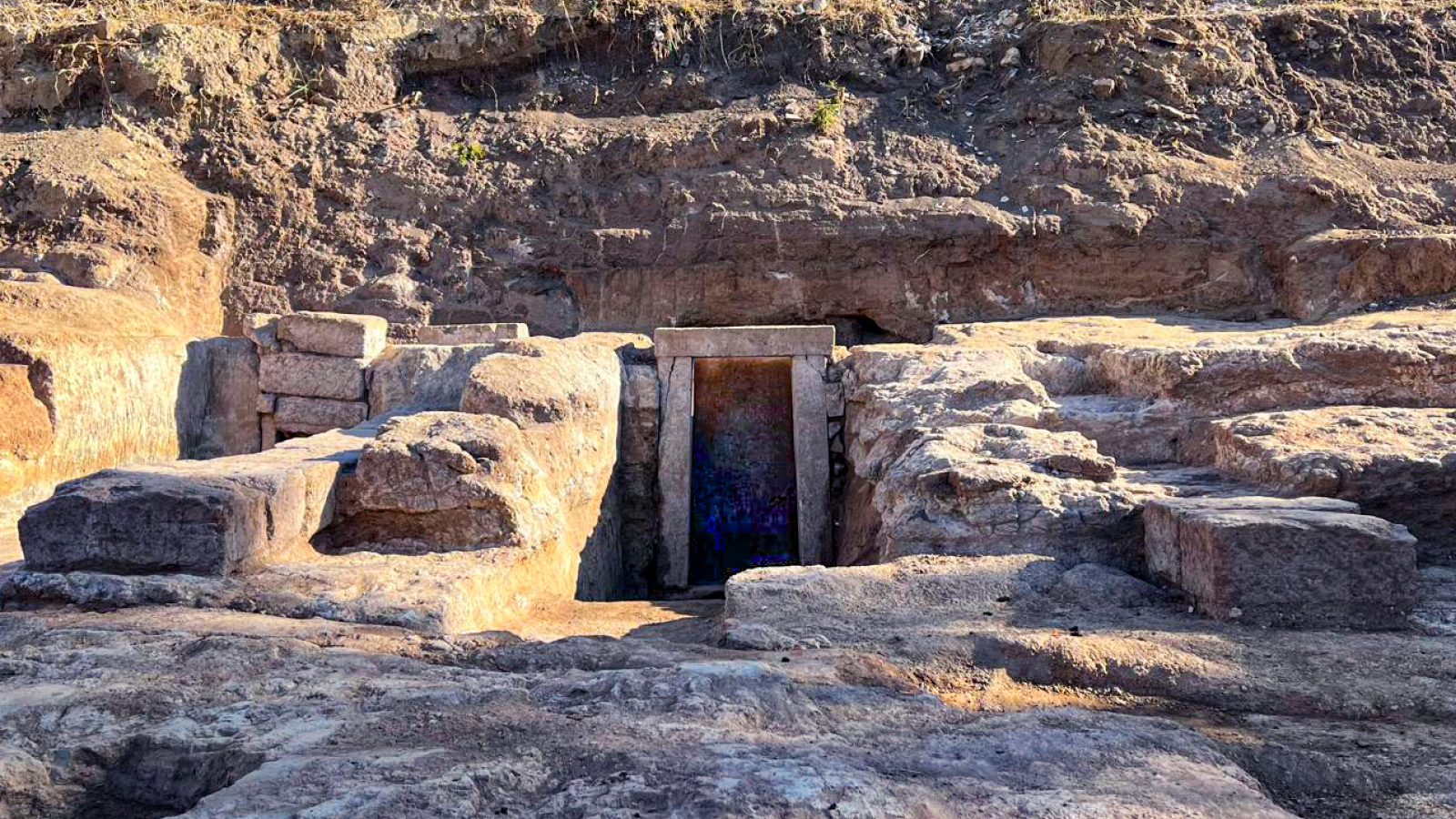

2,400-year-old Hercules shrine and elite tombs discovered outside ancient Rome's walls

2,400-year-old Hercules shrine and elite tombs discovered outside ancient Rome's walls

Romans regularly soaked in filthy, lead-contaminated bath water, Pompeii study finds

Romans regularly soaked in filthy, lead-contaminated bath water, Pompeii study finds

1,700-year-old Roman marching camps discovered in Germany — along with a multitude of artifacts like coins and the remnants of shoes

1,700-year-old Roman marching camps discovered in Germany — along with a multitude of artifacts like coins and the remnants of shoes

Diarrhea and stomachaches plagued Roman soldiers stationed at Hadrian's Wall, discovery of microscopic parasites finds

Diarrhea and stomachaches plagued Roman soldiers stationed at Hadrian's Wall, discovery of microscopic parasites finds

Pompeii victims were wearing woolen cloaks in August when they died — but experts are split on what that means

Pompeii victims were wearing woolen cloaks in August when they died — but experts are split on what that means

'This has re-written our understanding of Roman concrete manufacture': Abandoned Pompeii worksite reveal how self-healing concrete was made

Latest in News

'This has re-written our understanding of Roman concrete manufacture': Abandoned Pompeii worksite reveal how self-healing concrete was made

Latest in News

South Carolina's measles outbreak nears 790 cases — making it the biggest in decades

South Carolina's measles outbreak nears 790 cases — making it the biggest in decades

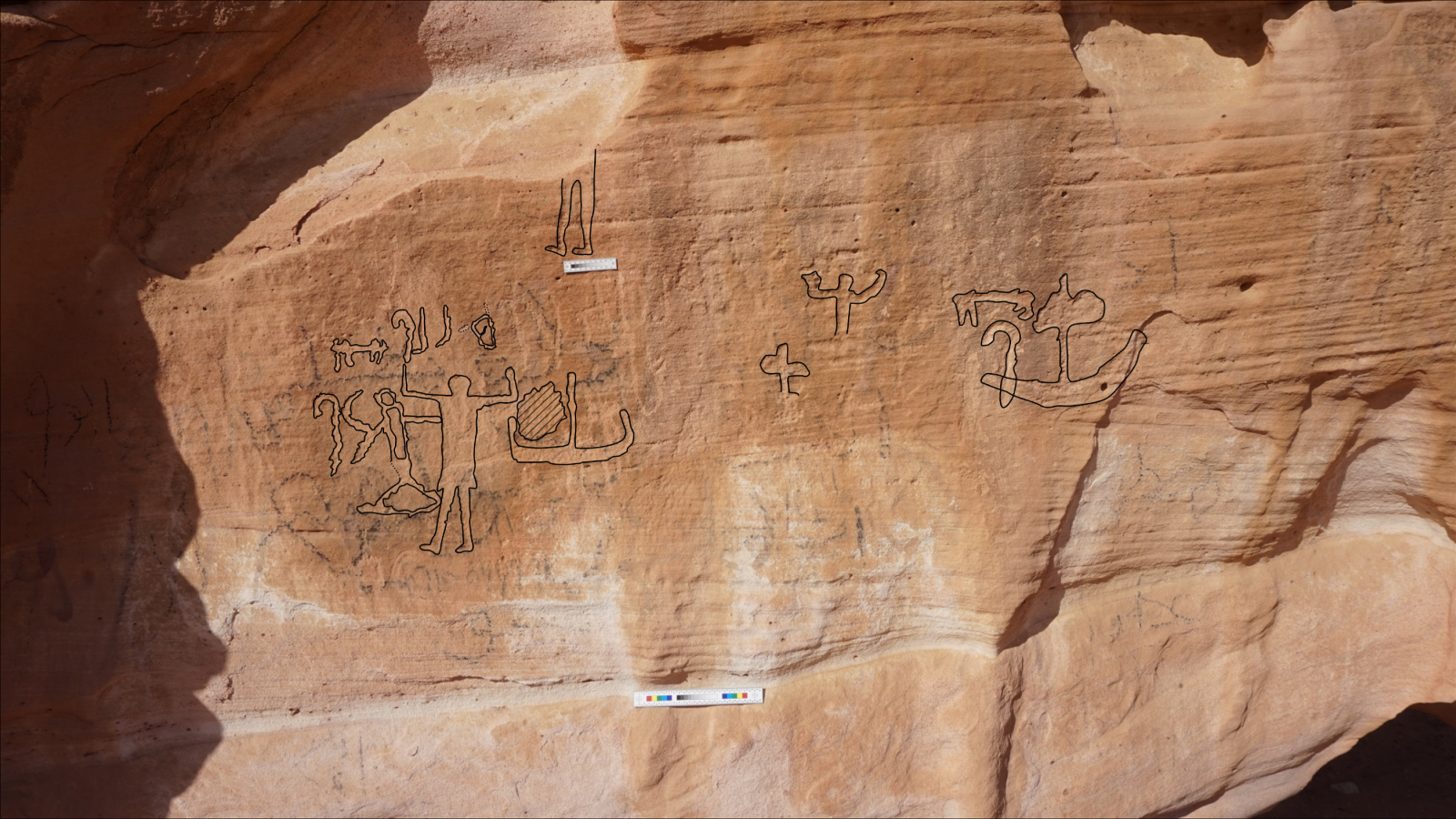

5,000-year-old rock art from ancient Egypt depicts 'terrifying' conquest of the Sinai Peninsula

5,000-year-old rock art from ancient Egypt depicts 'terrifying' conquest of the Sinai Peninsula

Stone Age teenager was mauled by a bear 28,000 years ago, skeletal analysis confirms

Stone Age teenager was mauled by a bear 28,000 years ago, skeletal analysis confirms

NASA jet crashes in flames on Texas runway — taking it out of the Artemis II mission

NASA jet crashes in flames on Texas runway — taking it out of the Artemis II mission

Critical moment when El Niño started to erode Russia's Arctic sea ice discovered

Critical moment when El Niño started to erode Russia's Arctic sea ice discovered

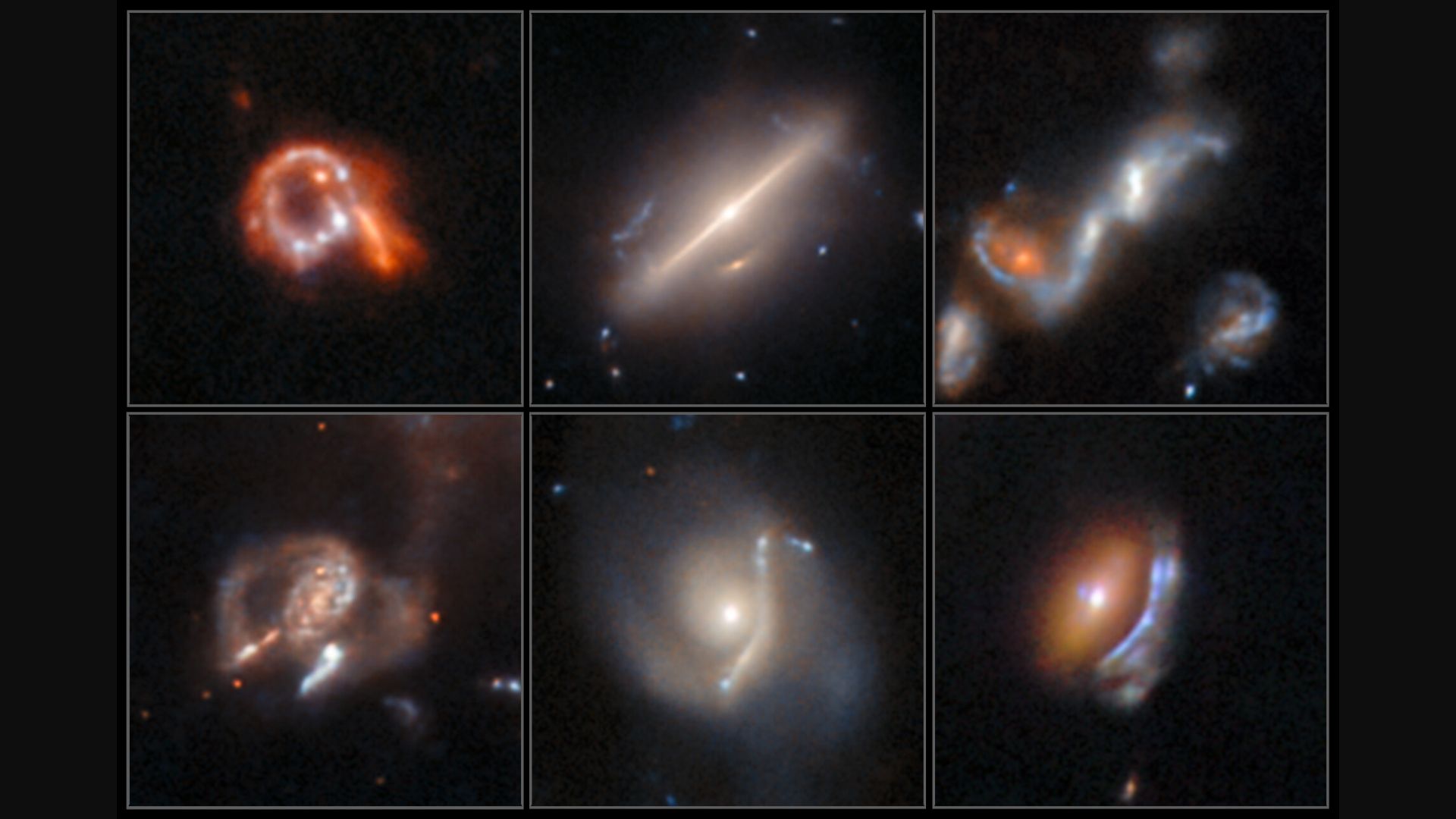

AI spots 'jellyfish,' 'hamburgers' and other unexplainable objects in Hubble telescope data

LATEST ARTICLES

AI spots 'jellyfish,' 'hamburgers' and other unexplainable objects in Hubble telescope data

LATEST ARTICLES 150-year-old NASA jet crashes in flames on Texas runway — taking it out of the Artemis II mission

150-year-old NASA jet crashes in flames on Texas runway — taking it out of the Artemis II mission- 25,000-year-old rock art from ancient Egypt depicts 'terrifying' conquest of the Sinai Peninsula

- 3Stone Age teenager was mauled by a bear 28,000 years ago, skeletal analysis confirms

- 4February 2026 night sky: What to see and what you need

- 5Drones could achieve 'infinite flight' after engineers create laser-based wireless power system that charges them from the ground