- Planet Earth

- Arctic

Scientists discover a tipping point that took place in 2000, where El Niño’s effect on sea ice loss in Siberia was amplified.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

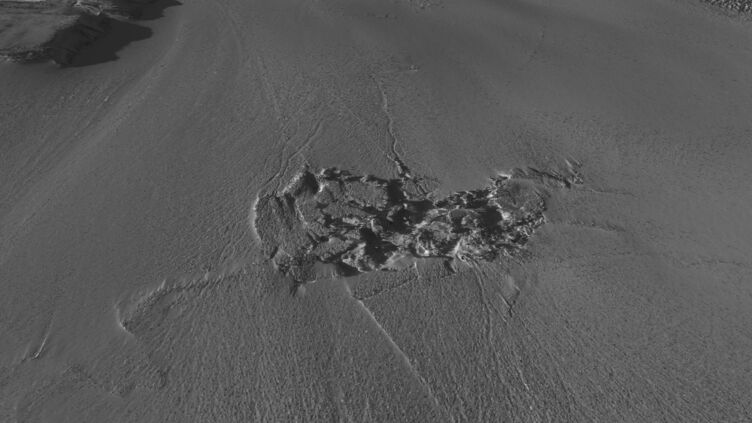

The El Nino-Southern Oscillation affects sea ice northeast of Russia more strongly since 2000, a new study finds.

(Image credit: steve_is_on_holiday/Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

The El Nino-Southern Oscillation affects sea ice northeast of Russia more strongly since 2000, a new study finds.

(Image credit: steve_is_on_holiday/Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Scientists have identified a tipping point that has amplified El Niño’s effect on sea ice loss in the Arctic.

For years, researchers have known of a feedback loop linking the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and sea ice coverage at high latitudes. But in a new study, researchers found that since around the year 2000, faster transitions between phases of ENSO have a stronger influence on ice loss northeast of Russia. These changes lead to warmer, wetter weather in the region and less sea ice coverage during the fall following the transition.

You may like-

Global warming is forcing Earth's systems toward 'doom loop' tipping points. Can we avoid them?

Global warming is forcing Earth's systems toward 'doom loop' tipping points. Can we avoid them?

-

Huge ice dome in Greenland vanished 7,000 years ago — melting at temperatures we're racing toward today

Huge ice dome in Greenland vanished 7,000 years ago — melting at temperatures we're racing toward today

-

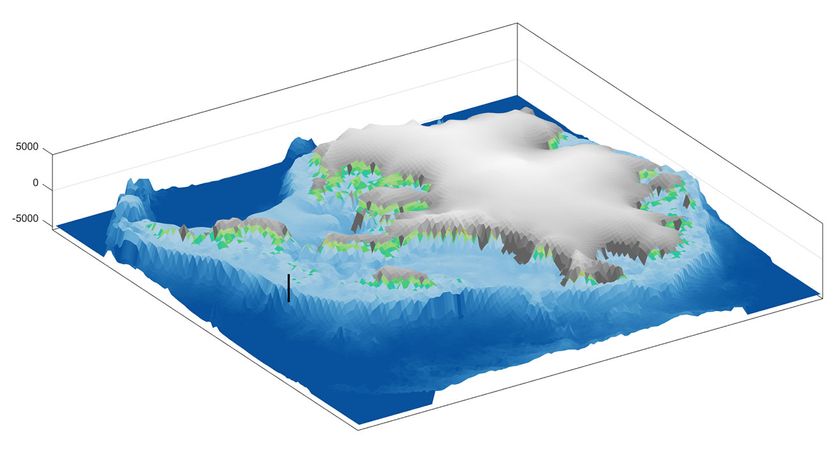

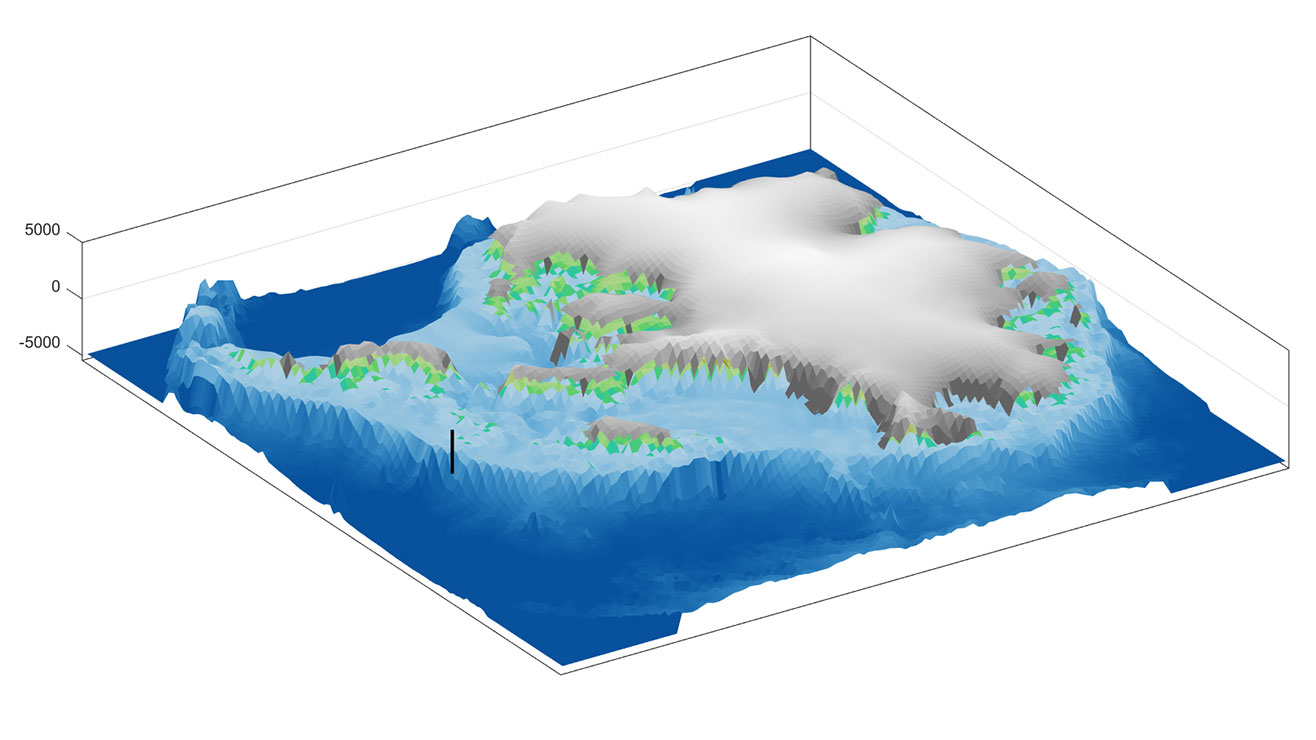

Melting of West Antarctic ice sheet could trigger catastrophic reshaping of the land beneath

Melting of West Antarctic ice sheet could trigger catastrophic reshaping of the land beneath

ENSO is a climate phenomenon involving variations in air pressure and sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific over multiple years. These variations can affect climate and weather patterns across the world, including the frequency of hurricanes, tropical cyclones and droughts.

In the new study, published Jan. 14 in the journal Science Advances, researchers explored how ENSO affects Arctic sea ice, focusing specifically on the Laptev and East Siberian seas northeast of Russia. The team combed through monthly data on sea surface temperatures and sea ice concentration that were collected between 1979 and 2023 to find patterns between ENSO transitions and sea ice coverage the following year.

The results showed that shifting out of the El Niño phase forms areas of cold surface waters in the central and eastern Pacific near the tropics during the following fall. After the year 2000, the transitions out of El Niño started to speed up, possibly due to interactions with the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, another long-term climate cycle that affects temperatures in the Pacific Ocean.

Those fast transitions made the cold patches even colder. And those cold areas pushed a high-pressure system known as the Western North Pacific Anticyclone (WNPAC) northward towards the Arctic. Pushing the WNPAC north causes another anticyclone to form above the Laptev and East Siberian seas. Together, these connected processes pull heat and moisture from the north Pacific into the Arctic, melting ice along the way.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.Prior to 2000, the connection between the cold areas and the WNPAC wasn't strong enough to affect sea ice coverage in the Arctic, the team found.

RELATED STORIES—'Mega' El Niño may have fueled Earth's biggest mass extinction

—Scientists say they can now forecast El Niño Southern Oscillation years in advance

—There's a 2nd El Niño — and scientists just figured out how it works

The changes that have occurred since 2000 are due to natural cycles in Earth's climate, not human activities, the researchers said. But anthropogenic climate change "is putting a big uncertainty on how we predict those multi-decade ice changes," said Xiaojun Yuan, a physical oceanographer at the Columbia University Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory who was not involved in the study.

Human-caused climate change could override some of the natural patterns observed in these long-term oscillations, Yuan told Live Science.

In future work, the team will investigate the effects of anthropogenic climate change on sea ice in the region, Wang said.

Skyler WareSocial Links NavigationLive Science Contributor

Skyler WareSocial Links NavigationLive Science ContributorSkyler Ware is a freelance science journalist covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has also appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, among others. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Global warming is forcing Earth's systems toward 'doom loop' tipping points. Can we avoid them?

Global warming is forcing Earth's systems toward 'doom loop' tipping points. Can we avoid them?

Huge ice dome in Greenland vanished 7,000 years ago — melting at temperatures we're racing toward today

Huge ice dome in Greenland vanished 7,000 years ago — melting at temperatures we're racing toward today

Melting of West Antarctic ice sheet could trigger catastrophic reshaping of the land beneath

Melting of West Antarctic ice sheet could trigger catastrophic reshaping of the land beneath

Antarctica's Southern Ocean might be gearing up for a thermal 'burp' that could last a century

Antarctica's Southern Ocean might be gearing up for a thermal 'burp' that could last a century

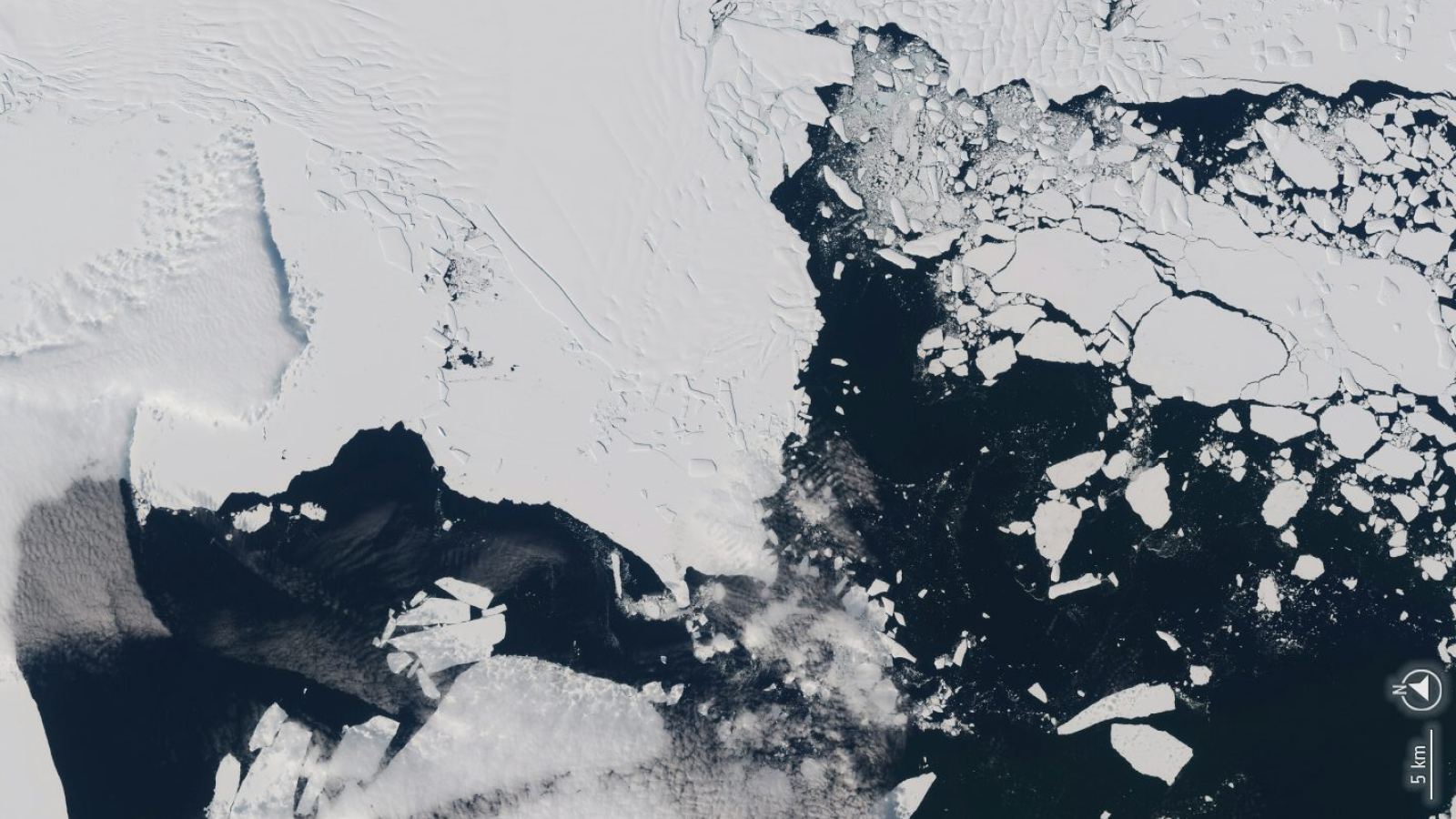

Hundreds of iceberg earthquakes are shaking the crumbling end of Antarctica's Doomsday Glacier

Hundreds of iceberg earthquakes are shaking the crumbling end of Antarctica's Doomsday Glacier

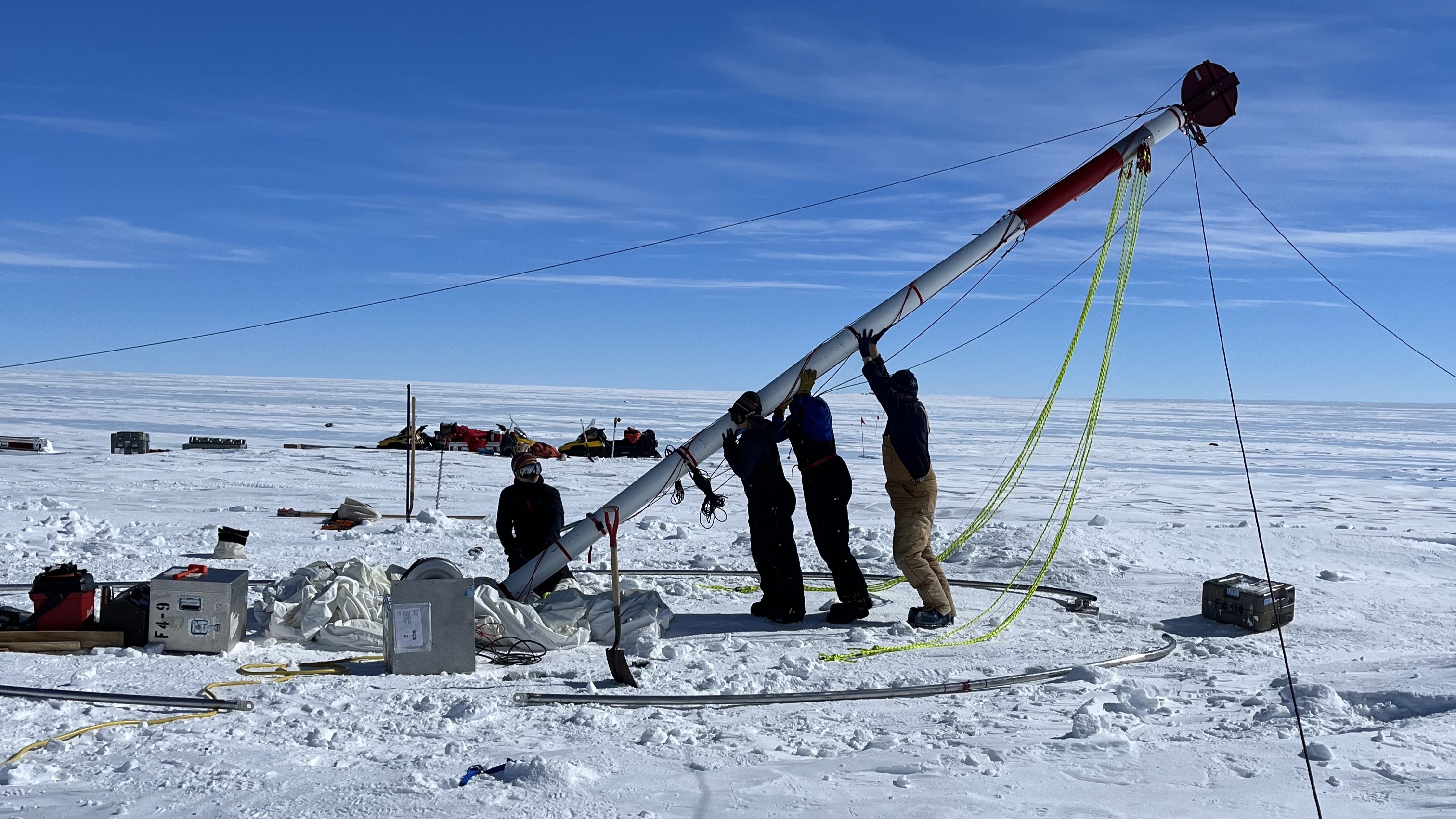

6 million-year-old ice discovered in Antarctica shatters records — and there's ancient air trapped inside

Latest in Arctic

6 million-year-old ice discovered in Antarctica shatters records — and there's ancient air trapped inside

Latest in Arctic

Huge ice dome in Greenland vanished 7,000 years ago — melting at temperatures we're racing toward today

Huge ice dome in Greenland vanished 7,000 years ago — melting at temperatures we're racing toward today

Arctic 'methane bomb' may not explode as permafrost thaws, new study suggests

Arctic 'methane bomb' may not explode as permafrost thaws, new study suggests

Scientists 'reawaken' ancient microbes from permafrost — and discover they start churning out CO2 soon after

Scientists 'reawaken' ancient microbes from permafrost — and discover they start churning out CO2 soon after

'It was so unexpected': 90 billion liters of meltwater punched its way through Greenland ice sheet in never-before-seen melting event

'It was so unexpected': 90 billion liters of meltwater punched its way through Greenland ice sheet in never-before-seen melting event

New technologies are helping to regrow Arctic sea ice

New technologies are helping to regrow Arctic sea ice

Scientists record never-before-seen 'ice quakes' deep inside Greenland's frozen rivers

Latest in News

Scientists record never-before-seen 'ice quakes' deep inside Greenland's frozen rivers

Latest in News

Critical moment when El Niño started to erode Russia's Arctic sea ice discovered

Critical moment when El Niño started to erode Russia's Arctic sea ice discovered

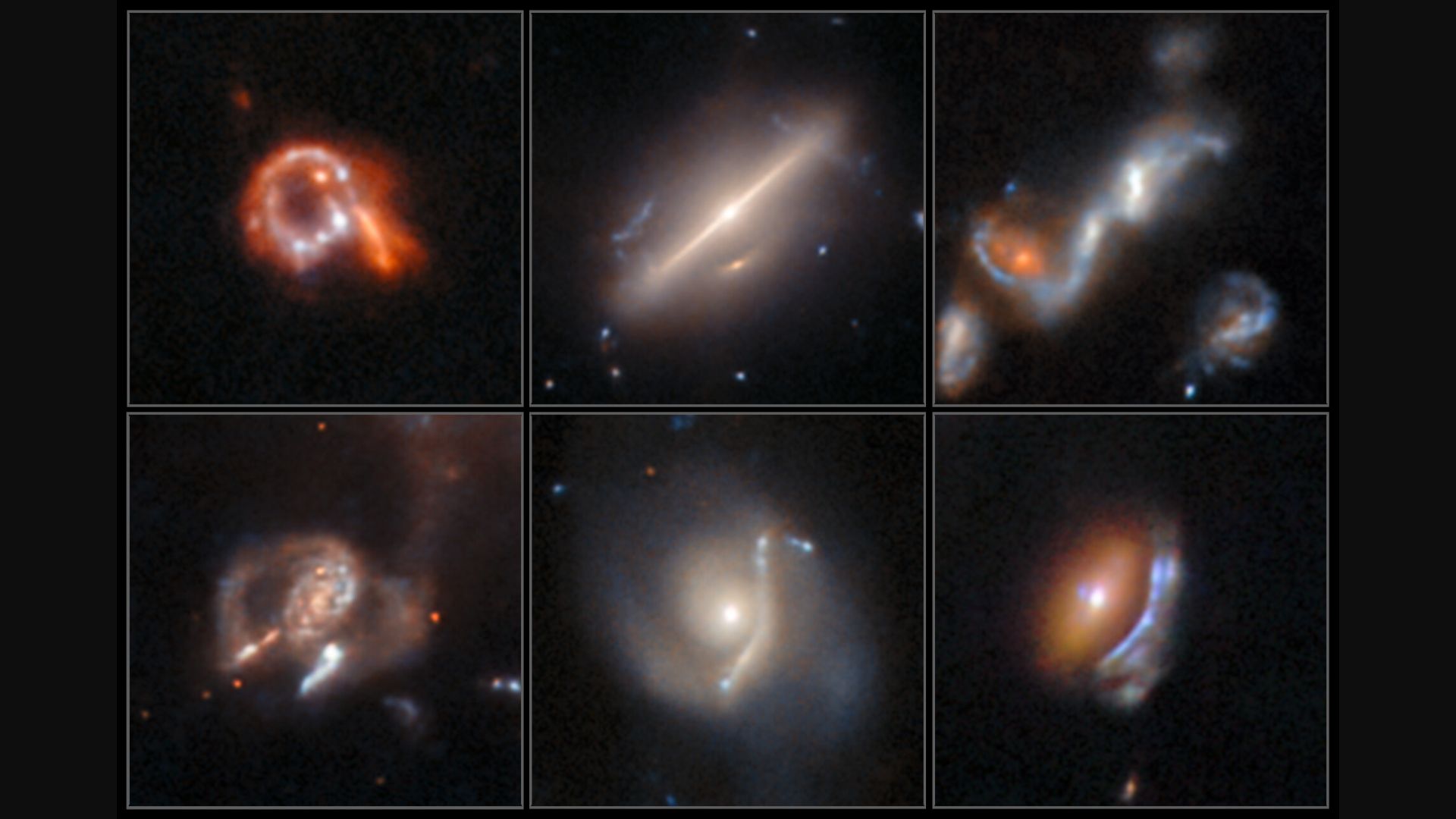

AI spots 'jellyfish,' 'hamburgers' and other unexplainable objects in Hubble telescope data

AI spots 'jellyfish,' 'hamburgers' and other unexplainable objects in Hubble telescope data

Romans used human feces as medicine 1,900 years ago — and used thyme to mask the smell

Romans used human feces as medicine 1,900 years ago — and used thyme to mask the smell

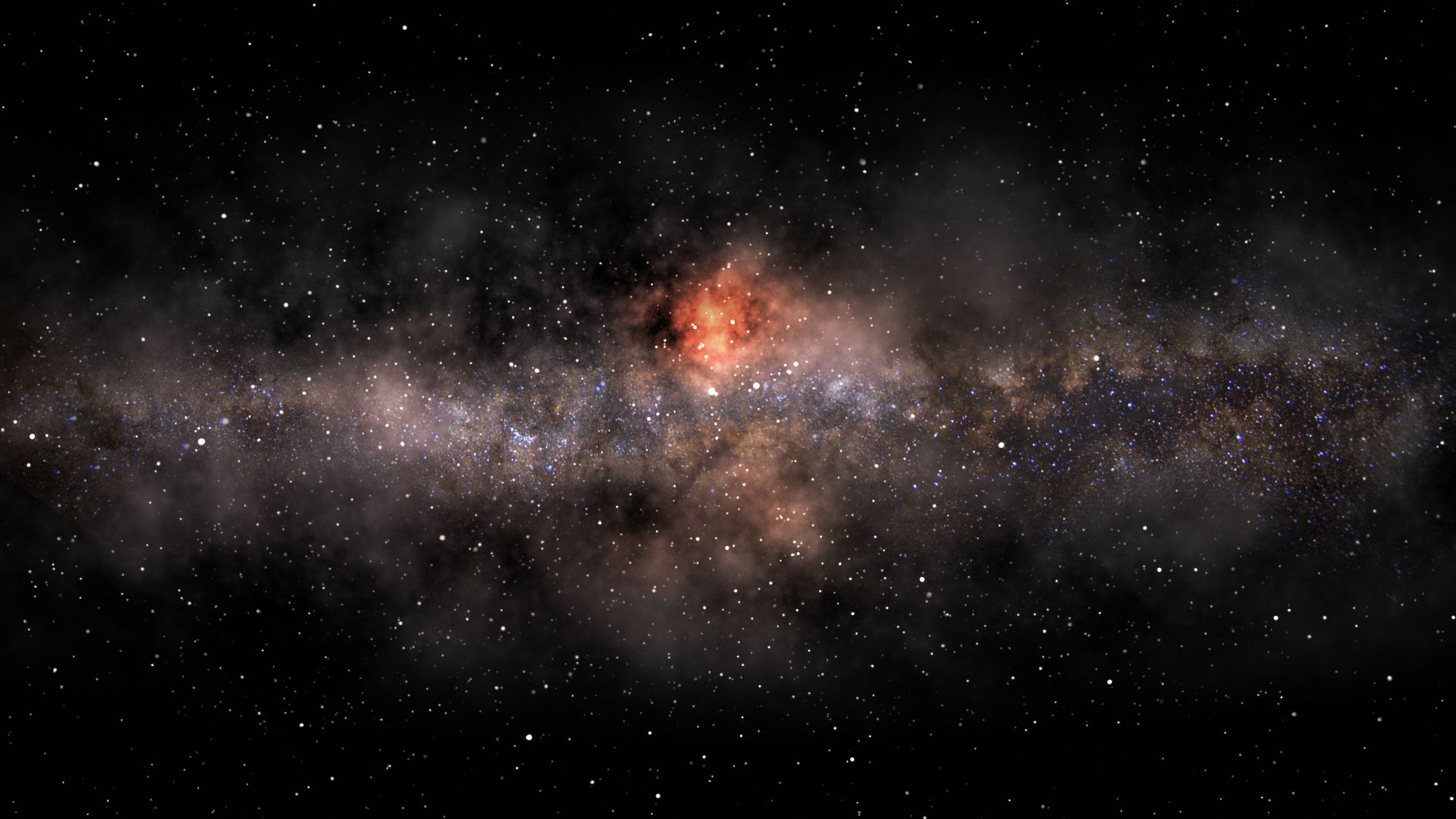

Complex building blocks of life can form on space dust — offering new clues to the origins of life

Complex building blocks of life can form on space dust — offering new clues to the origins of life

Can AI detect cognitive decline better than a doctor? New study reveals surprising accuracy

Can AI detect cognitive decline better than a doctor? New study reveals surprising accuracy

430,000-year-old wooden handheld tools from Greece are the oldest on record — and they predate modern humans

LATEST ARTICLES

430,000-year-old wooden handheld tools from Greece are the oldest on record — and they predate modern humans

LATEST ARTICLES 1AI spots 'jellyfish,' 'hamburgers' and other unexplainable objects in Hubble telescope data

1AI spots 'jellyfish,' 'hamburgers' and other unexplainable objects in Hubble telescope data- 2Teenage girl who lived in Italy 12,000 years ago had a rare form of dwarfism, DNA study shows

- 3Complex building blocks of life can form on space dust — offering new clues to the origins of life

- 4Can AI detect cognitive decline better than a doctor? New study reveals surprising accuracy

- 5430,000-year-old wooden handheld tools from Greece are the oldest on record — and they predate modern humans