- Health

- Viruses, Infections & Disease

- Cancer

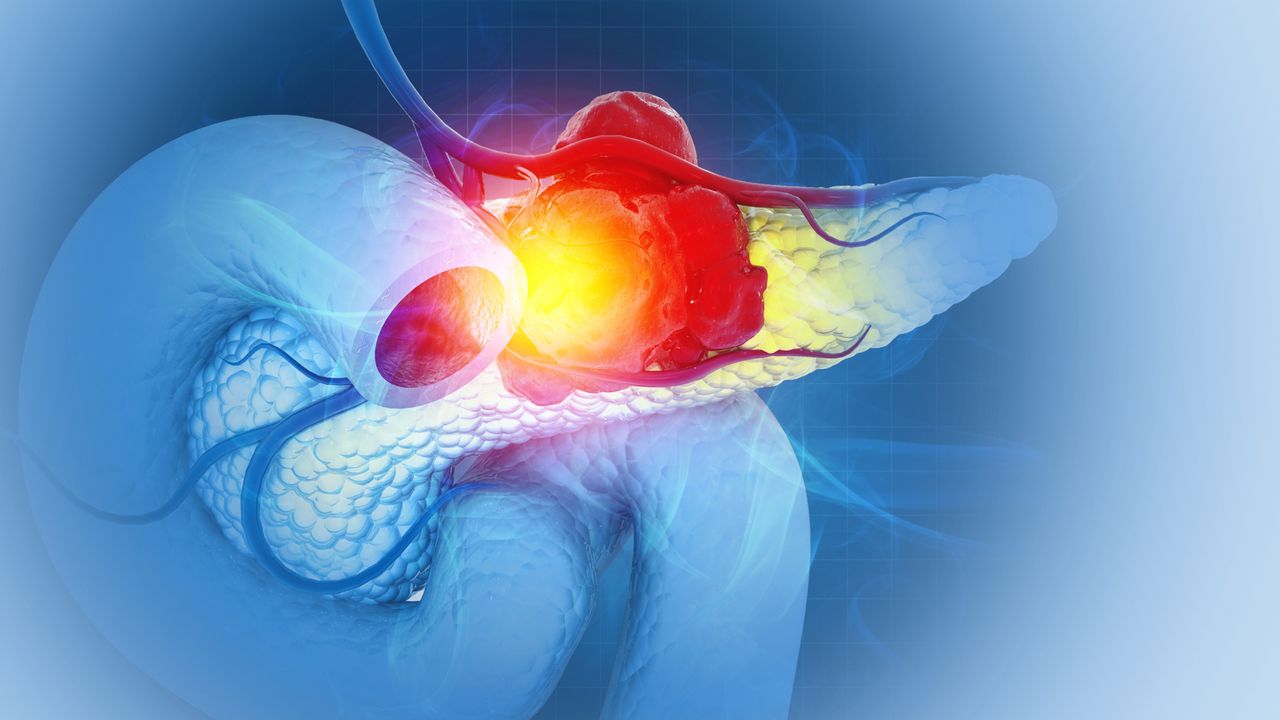

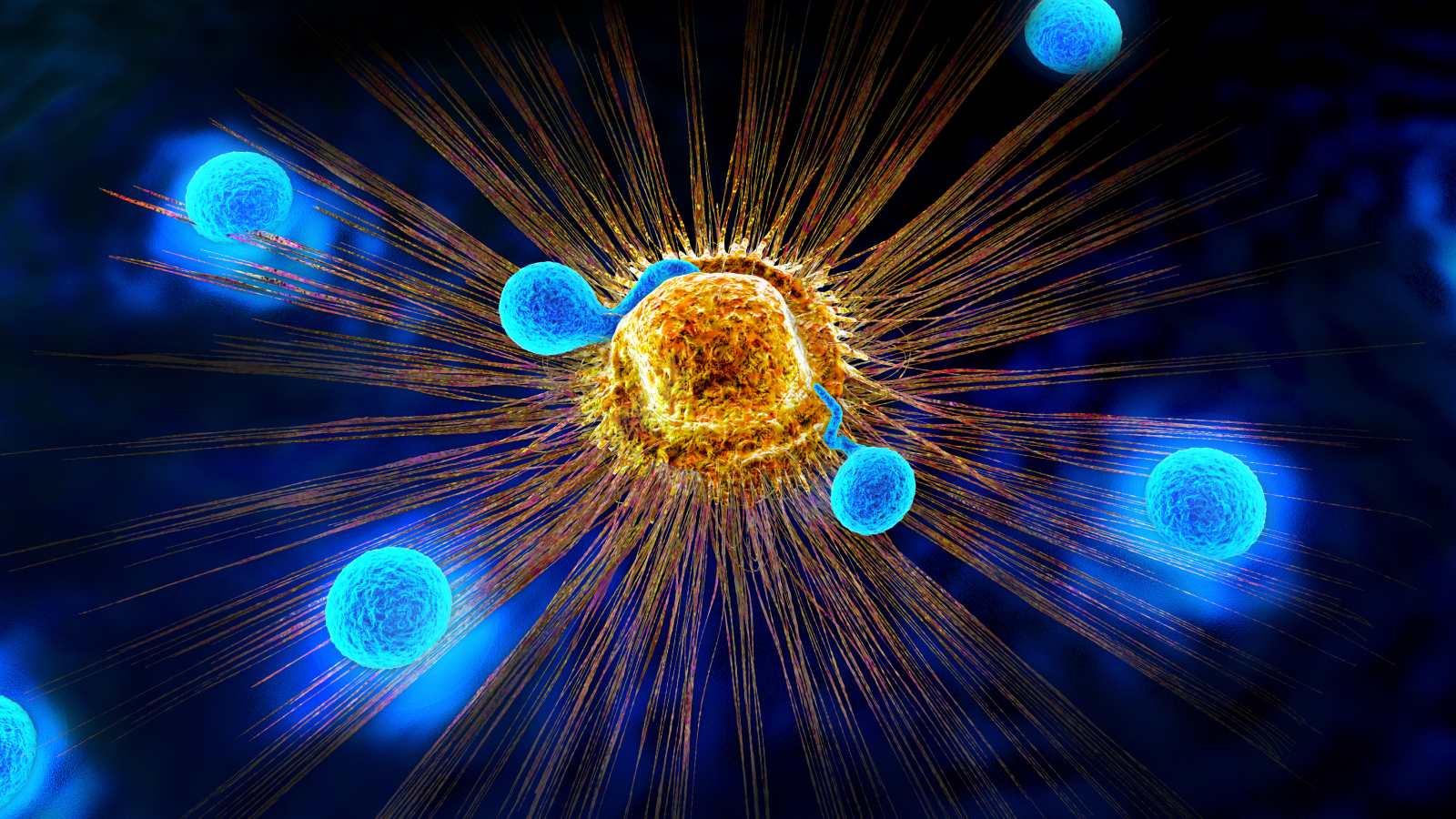

By targeting three key growth pathways at once, researchers eliminated pancreatic tumors in multiple mouse models and prevented the cancer from returning, a promising step toward overcoming treatment resistance.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

Recent mouse experiments point to a promising new treatment approach for pancreatic cancer.

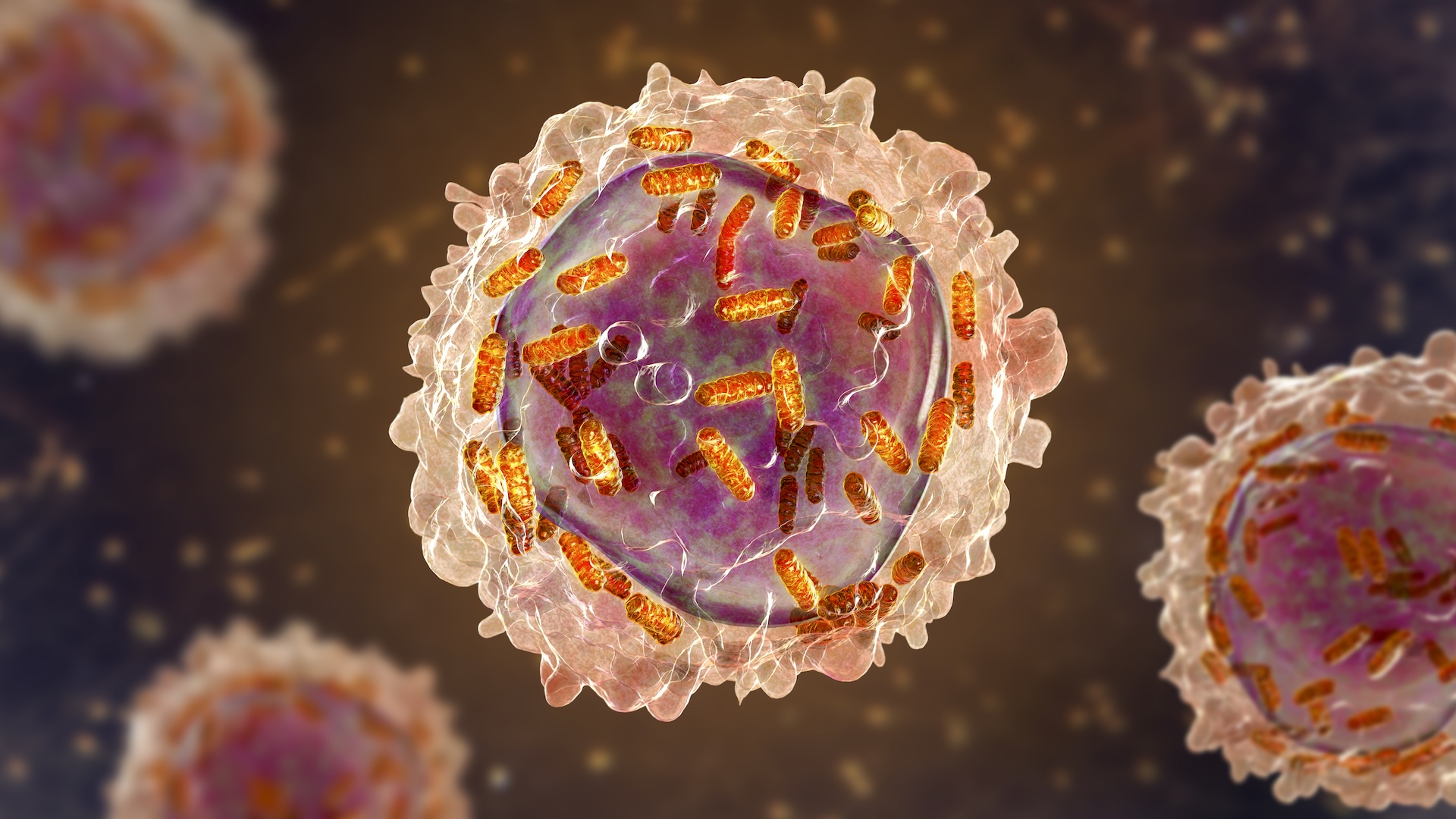

(Image credit: Mohammed Haneefa Nizamudeen via Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

Recent mouse experiments point to a promising new treatment approach for pancreatic cancer.

(Image credit: Mohammed Haneefa Nizamudeen via Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

A triple-drug therapy for pancreatic cancer has shown promise in early animal tests, pointing to a potential new treatment for a disease with a notoriously low survival rate.

Considered one of the deadliest common cancers, pancreatic cancer has a five-year relative survival rate around 13% — meaning roughly 87% of people with the cancer are expected to die within five years of diagnosis. That survival rate can plummet as low as 1% for people diagnosed in very late stages of the disease.

You may like-

It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

-

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

-

New drug could prevent diabetes complications not fixed with blood sugar control, study hints

New drug could prevent diabetes complications not fixed with blood sugar control, study hints

"These studies open a path to designing new combination therapies that can improve survival for patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [the most common pancreatic cancer]," the study authors said in a statement. "These results point the way for developing new clinical trials."

Early-stage pancreatic cancer grows silently inside the abdomen without any obvious symptoms. By the time the disease is detected, it has often already spread to other organs, making it difficult to remove surgically.

Standard treatments like chemotherapies attack all rapidly dividing cells in the body, often causing a lot of collateral damage in the process of controlling tumor growth. And even then, tumors usually find alternative ways to multiply and become resistant to treatment.

The new therapy not only prevented the rodents' cancer from coming back, but it was also non-toxic for mice overall, showing no debilitating side effects.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.Nearly all pancreatic cancers are associated with a mutation in a gene called "KRAS," which normally controls cell division and growth, keeping it in check. But when the gene is mutated, it gets stuck in an "on" position, leading to abnormal rate of cell division and cancer.

Prior to the current research, senior study author Carmen Guerra, a cancer biologist at the Experimental Oncology Group of the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), developed mouse models to investigate how KRAS mutations and other related pathways help pancreatic tumors survive. While blocking certain KRAS-related pathways can stop small tumors from growing, larger tumors often adapt to "open another door" for survival, she told Live Science.

In their latest work, Guerra and her team analyzed these resistant tumors, discovering that a protein called STAT3 became highly active when other growth routes were blocked. That suggested that it might be acting as the emergency backup pathway for tumor growth.

You may like-

It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

-

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

-

New drug could prevent diabetes complications not fixed with blood sugar control, study hints

New drug could prevent diabetes complications not fixed with blood sugar control, study hints

The team tried genetically blocking this pathway in mouse tumor cells, along with other major tumor-growth drivers. And they observed that the tumors regressed, confirming that STAT3 was indeed a key "mechanism of resistance," Guerra said.

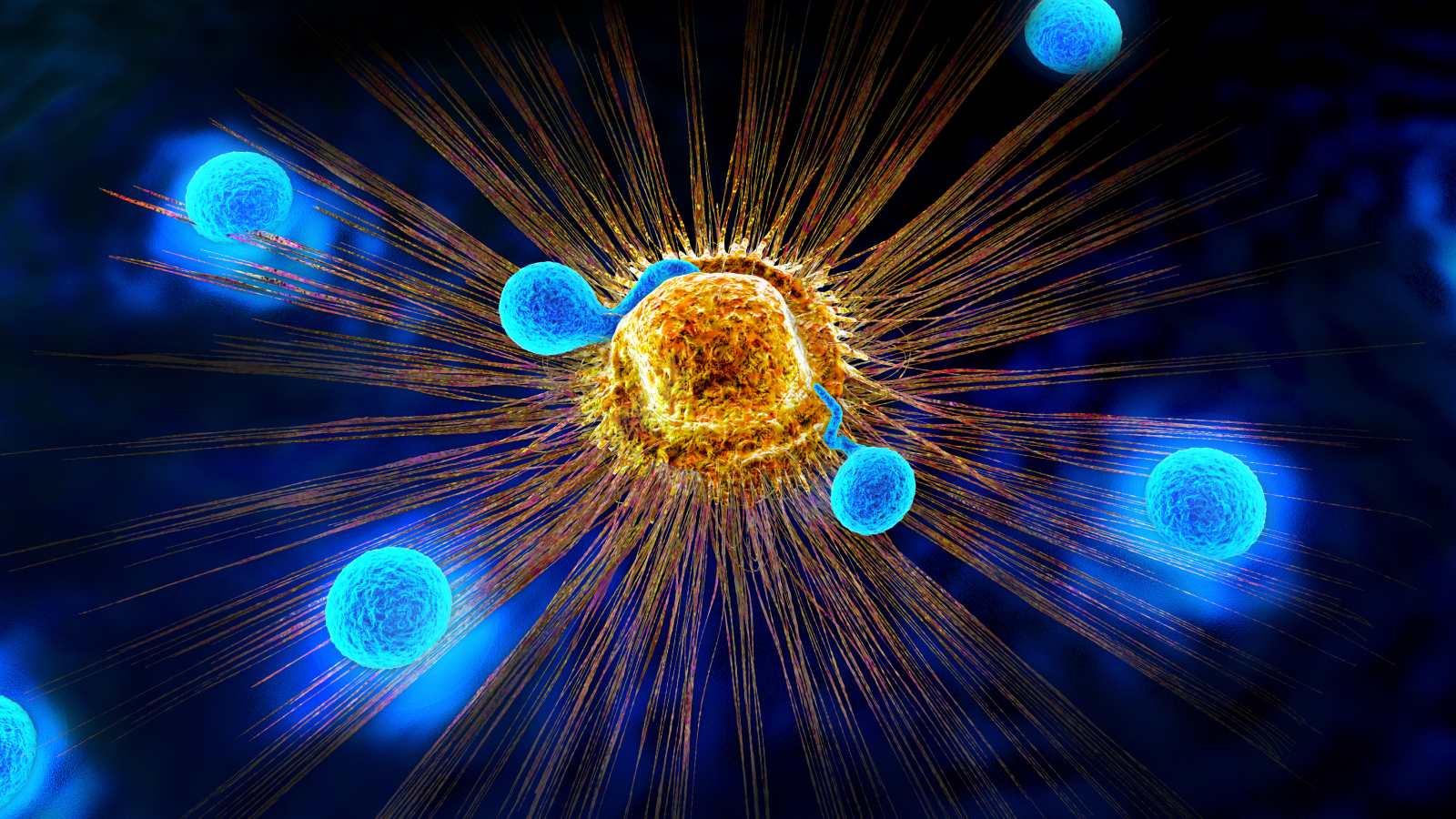

At that point, the researchers had confirmed that genetically shutting down three pathways — KRAS, a KRAS-related pathway, and STAT3 — could eliminate tumors. So they set about testing a drug-based version of the strategy.

This triple-pronged approach includes two existing drugs: afatinib, which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for certain lung cancers, and daraxonrasib, which is currently being tested in clinical trials. The third drug is a newer compound designed to disable STAT3.

RELATED STORIES—'PAC-MANN' blood test aims to detect pancreatic cancer early

—When is cancer considered cured, versus in remission?

—Could simple blood tests identify cancer earlier?

The team evaluated this three-drug therapy in three types of mouse models: one in which tumor cells from mice are implanted directly into the mouse pancreas; one involving mice that were genetically engineered to develop pancreatic cancer; and one using human tumor samples grown in immune-deficient mice, to prevent mouse immune system from attacking foreign tissue. In all three models, the combination treatment eliminated the tumors completely.

"You couldn't even see where the tumor was," Guerra told Live Science. "The pancreas was completely healthy."

The treatment also prevented resistance, as the team reported that the tumors did not return for at least 200 days — or nearly seven months — after the treatment, which is longer than what most single-drug therapies achieve in similar mouse models.

Importantly, the triple-drug therapy did not cause toxic or severe side effects in mice. The rodents receiving the therapy showed similar body weight, blood counts, metabolic markers and organ health when compared to tumor-bearing mice given a placebo treatment.

However, given this new research was in mice, there could be some differences in human pancreatic cancer patients. Guerra noted that mice can be "more resistant to this kind of toxicity" than humans are. While the therapy didn't show any side effects in mice, some drugs they used, like afatinib, have already been tested in humans and are known to have some side effects, such as skin and gastrointestinal issues.

So, the researchers are now working to find alternatives and "develop better drugs" that hit the same pathways, she told Live Science.

Guerra also stressed that pancreatic tumors are genetically diverse, and patients can have "tons of alterations," making each case different to the next. On that front, the team will also study additional mouse models that carry other common KRAS mutations, as well as changes in other cancer-related genes, to test the effectiveness of the therapy in a diverse range of tumors, she told Live Science.

DisclaimerThis article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Article SourcesLiaki, V., et al. (2025). A targeted combination therapy achieves effective pancreatic cancer regression and prevents tumor resistance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(49). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2523039122

Zunnash KhanLive Science Contributor

Zunnash KhanLive Science ContributorZunnash Khan is a mechatronics engineer and a science journalist from Pakistan. She has written for Science, The Scientist and Brainfacts.org, among other outlets.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

New drug could prevent diabetes complications not fixed with blood sugar control, study hints

New drug could prevent diabetes complications not fixed with blood sugar control, study hints

High-fiber diet may 'rejuvenate' immune cells that fight cancer, study finds

High-fiber diet may 'rejuvenate' immune cells that fight cancer, study finds

Slaying 'zombie cells' in blood vessels could be key to treating diabetes, early study finds

Slaying 'zombie cells' in blood vessels could be key to treating diabetes, early study finds

A 'functional cure' for HIV may be in reach, early trials suggest

Latest in Cancer

A 'functional cure' for HIV may be in reach, early trials suggest

Latest in Cancer

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

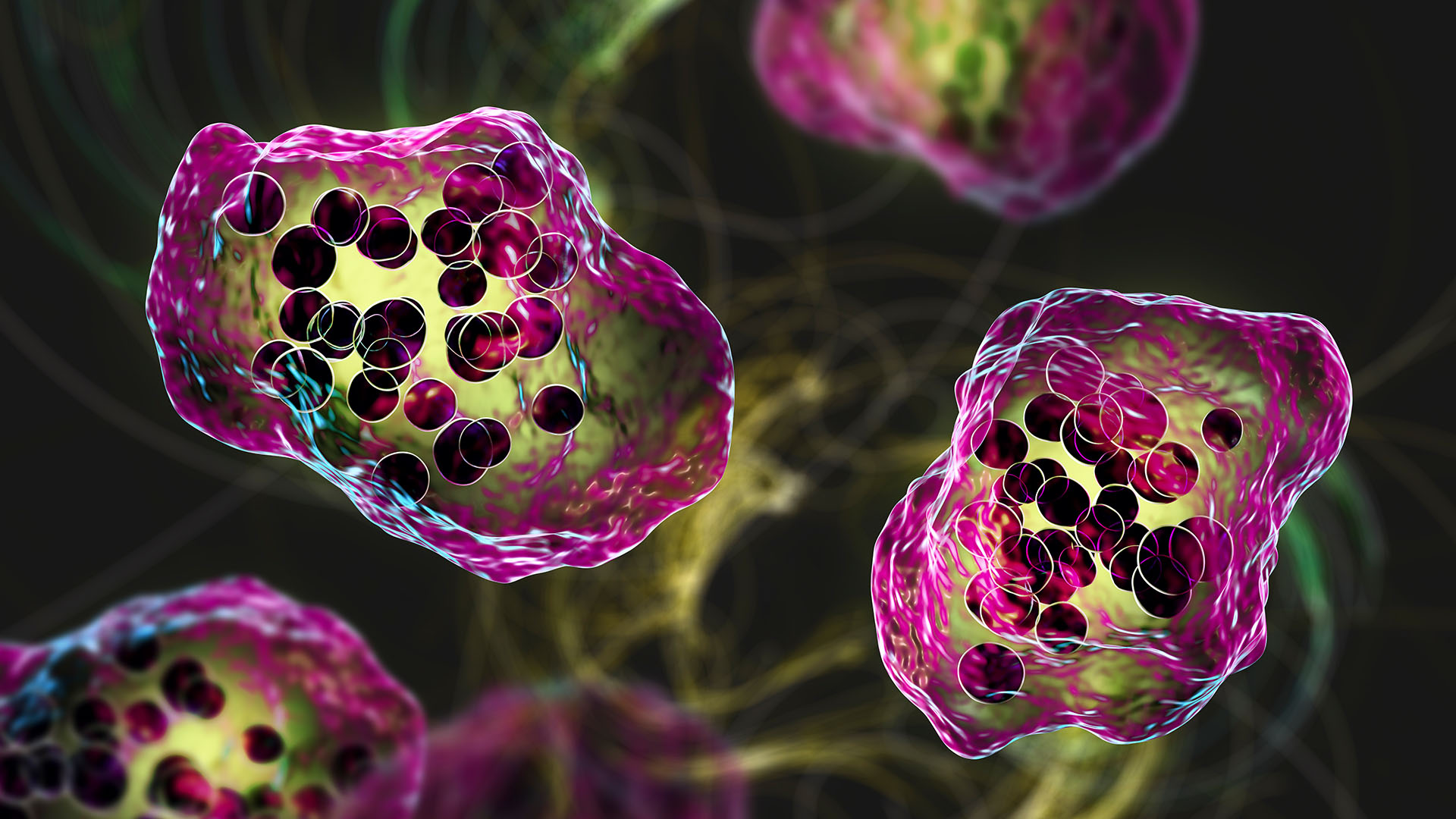

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

Science history: Female chemist initially barred from research helps develop drug for remarkable-but-short-lived recovery in children with leukemia — Dec. 6, 1954

Science history: Female chemist initially barred from research helps develop drug for remarkable-but-short-lived recovery in children with leukemia — Dec. 6, 1954

High-fiber diet may 'rejuvenate' immune cells that fight cancer, study finds

Latest in News

High-fiber diet may 'rejuvenate' immune cells that fight cancer, study finds

Latest in News

New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds

New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds

'Part of the evolutionary fabric of our societies': Same-sex sexual behavior in primates may be a survival strategy, study finds

'Part of the evolutionary fabric of our societies': Same-sex sexual behavior in primates may be a survival strategy, study finds

More than 43,000 years ago, Neanderthals spent centuries collecting animal skulls in a cave; but archaeologists aren't sure why

More than 43,000 years ago, Neanderthals spent centuries collecting animal skulls in a cave; but archaeologists aren't sure why

Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.

Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.

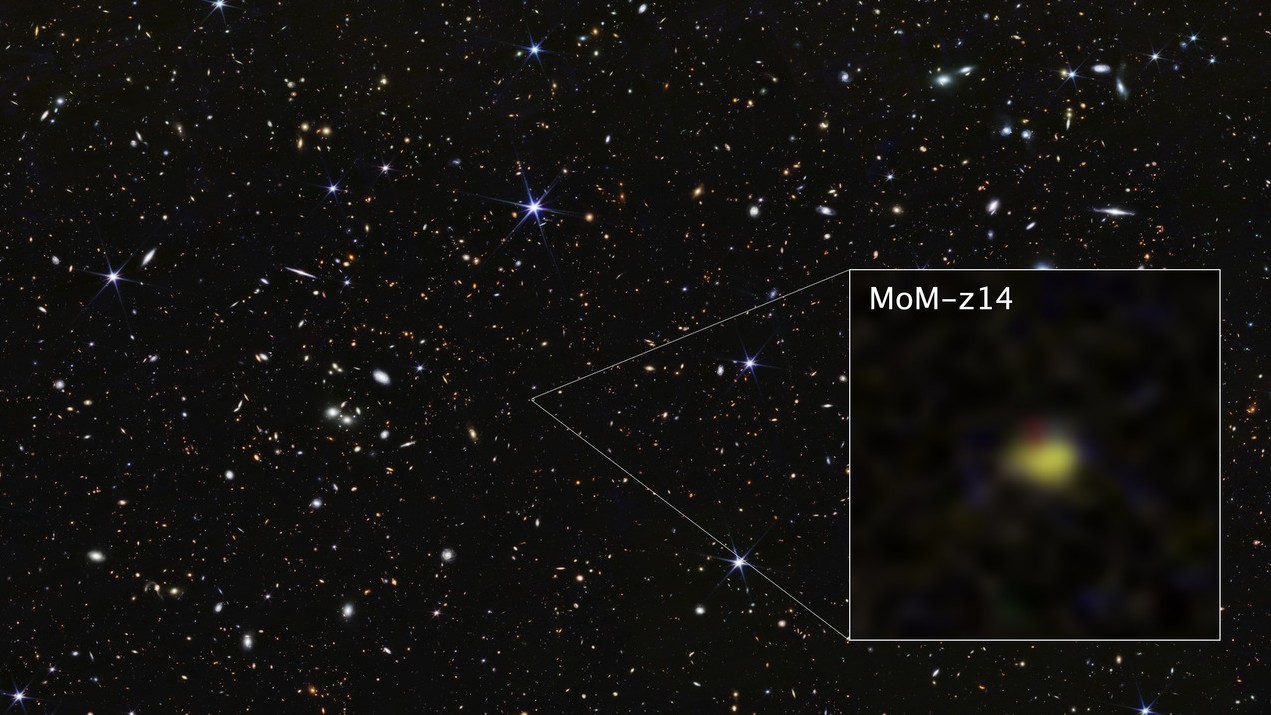

James Webb telescope breaks own record, discovering farthest known galaxy in the universe

James Webb telescope breaks own record, discovering farthest known galaxy in the universe

South Carolina's measles outbreak nears 790 cases — making it the biggest in decades

LATEST ARTICLES

South Carolina's measles outbreak nears 790 cases — making it the biggest in decades

LATEST ARTICLES 1Thousands of dams in the US are old, damaged and unable to cope with extreme weather. How bad is it?

1Thousands of dams in the US are old, damaged and unable to cope with extreme weather. How bad is it?- 2'Part of the evolutionary fabric of our societies': Same-sex sexual behavior in primates may be a survival strategy, study finds

- 3More than 43,000 years ago, Neanderthals spent centuries collecting animal skulls in a cave; but archaeologists aren't sure why

- 4Watch awkward Chinese humanoid robot lay it all down on the dance floor

- 5The Snow Moon will 'swallow' one of the brightest stars in the sky this weekend: Where and when to look