- Planet Earth

Dams in the U.S. are showing signs of damage that are worsening with age and climate change. Could satellites help prioritize repairs amid budget and inspection constraints?

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

Research suggests the ground is moving beneath Livingston Dam in Texas (pictured here after a controlled water release operation), potentially posing a risk of failure.

(Image credit: Brett Coomer/Houston Chronicle via Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

Research suggests the ground is moving beneath Livingston Dam in Texas (pictured here after a controlled water release operation), potentially posing a risk of failure.

(Image credit: Brett Coomer/Houston Chronicle via Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Satellite images have revealed that dozens of dams across the U.S. — including the biggest one in Texas — may be at risk of collapse due to the ground shifting beneath them. Inspections do not typically account for these movements, suggesting many dams in the country are in worse condition than previously understood.

The new findings raise the prospect that thousands of dams we haven't been monitoring closely due to high costs and staff shortages could be damaged and at risk of failure. But how big is the problem, and is it worth using satellite data to provide early warnings?

You may like-

18 of Earth's biggest river deltas — including the Nile and Amazon — are sinking faster than global sea levels are rising

18 of Earth's biggest river deltas — including the Nile and Amazon — are sinking faster than global sea levels are rising

-

Forced closure of premier US weather-modeling institute could endanger millions of Americans

Forced closure of premier US weather-modeling institute could endanger millions of Americans

-

'Nobody knew why this was happening': Scientists race to understand baffling behavior of 'clumping clouds'

'Nobody knew why this was happening': Scientists race to understand baffling behavior of 'clumping clouds'

Shifting ground

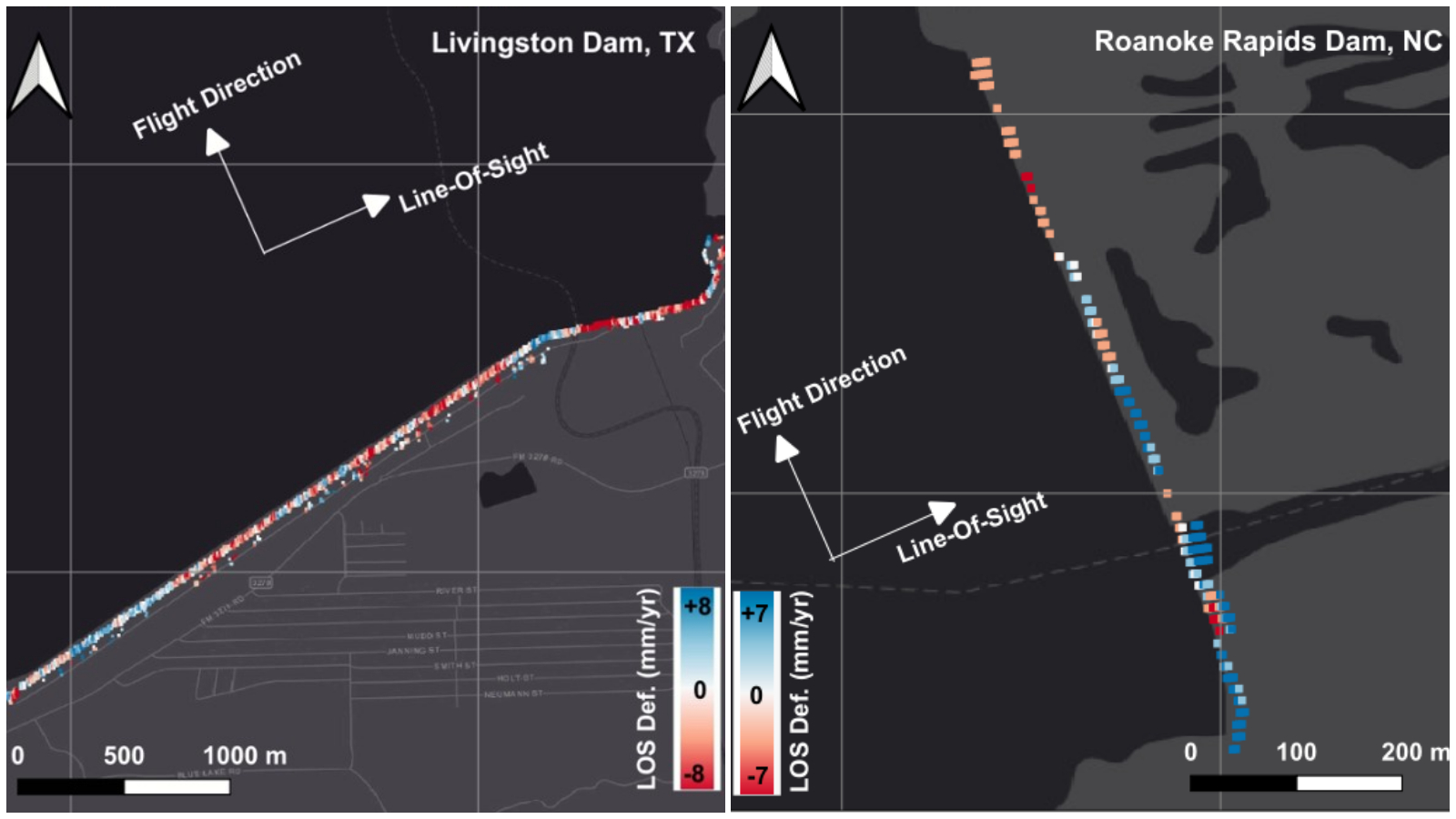

In a presentation to the American Geophysical Union in December 2025, scientists used 10 years of radar images from the Sentinel-1 satellite to identify dams that have shifted due to sinking or elevating ground. Depending on the material of the dam, this can lead to cracks forming, especially if different parts of the structure are moving in opposite directions or at varying rates.

"This technology helps us to find potential issues, and then inform the people who are in charge," lead researcher Mohammad Khorrami, a postdoctoral geotechnical engineer at Virginia Tech and The United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health, told Live Science.

The results are based on 41 high-hazard hydroelectric dams that are higher than 50 feet (15 meters), and whose condition is "poor" or "unsatisfactory" under the National Inventory of Dams' classification. These are dams with known defects that compromise the safety of operations and require repairs.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.The results are preliminary and have not been peer reviewed. Nevertheless, they show previously unknown weaknesses in dams across 13 U.S. states and Puerto Rico — including Roanoke Rapids Dam in North Carolina and Livingston Dam, the biggest dam in Texas.

Some of these high-risk dams are shifting considerably. For example, the northern portion of Livingston Dam — which feeds two water purification plants supplying more than 3 million people in Houston — is sinking at a rate of about 0.3 inches (8 millimeters) per year, while the southern portion is simultaneously rising by the same amount.

"That doesn't mean that part of the dam is collapsing," Khorrami said. But such elevation differences warrant further investigation, because they might turn out to be a problem, he added. Given that these dams are decades old, potentially faulty and affect both people downstream and energy supplies, deformations in the structure could be disastrous.

You may like-

18 of Earth's biggest river deltas — including the Nile and Amazon — are sinking faster than global sea levels are rising

18 of Earth's biggest river deltas — including the Nile and Amazon — are sinking faster than global sea levels are rising

-

Forced closure of premier US weather-modeling institute could endanger millions of Americans

Forced closure of premier US weather-modeling institute could endanger millions of Americans

-

'Nobody knew why this was happening': Scientists race to understand baffling behavior of 'clumping clouds'

'Nobody knew why this was happening': Scientists race to understand baffling behavior of 'clumping clouds'

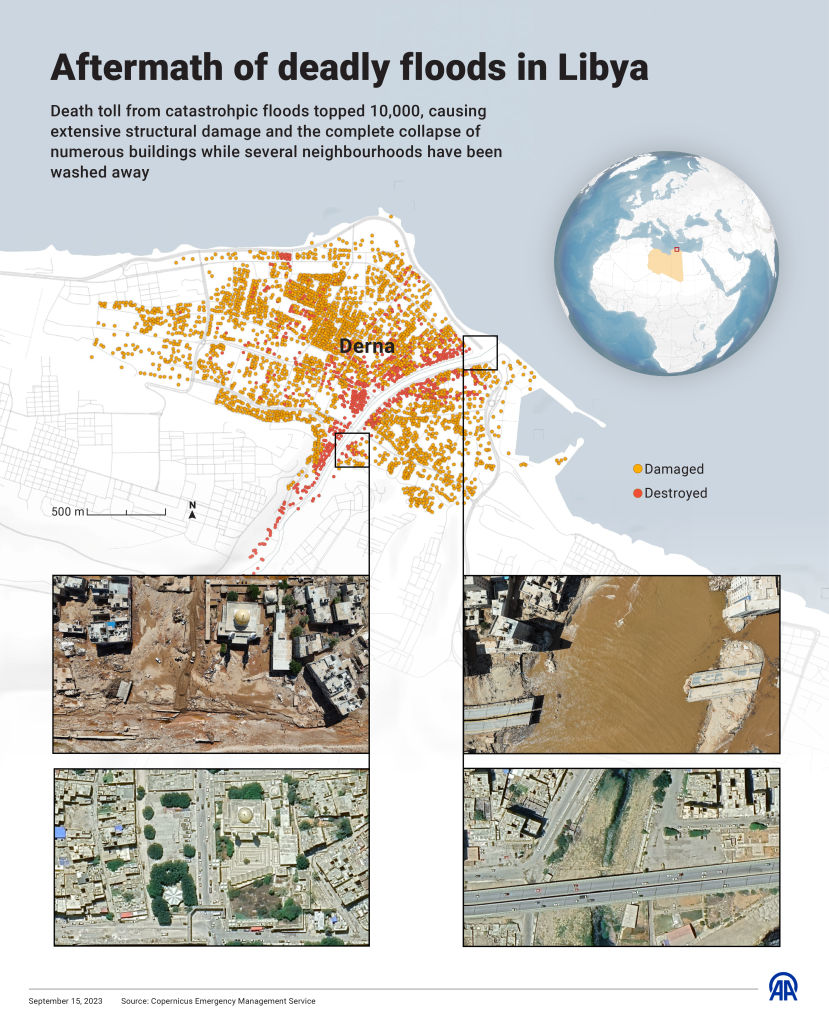

A tragic incident in Libya in 2023 suggests land elevation changes are not something to overlook. On Sept. 11, two dams collapsed following extreme rainfall from Storm Daniel. The failures unleashed 1 billion cubic feet (30 million cubic meters) — or 10,000 Olympic swimming pools — of water upon the city of Derna, destroying buildings and bridges, and killing up to 24,000 people.

Deformations in the dams resulting from land elevation changes likely contributed to the collapses, a 2025 study found. "The results of satellite imagery showed a constant and persistent deformation on both these dams during the last decade," Khorrami said. "So those dams were already vulnerable."

Khorrami and his colleagues are finalizing the results of their study. The next step will be to produce an interactive map or database that policymakers can use to assess the safety of U.S. dams.

"It's not a replacement for inspections," Khorrami said. "We're providing another tool to help find early warning signs if there is any issue, or potential issue, with the dam."

Aging infrastructure, changing climate

But ground shifts are just one factor that can compromise dams. The U.S. has almost 92,600 dams — more than 16,700 of which have a "high-hazard potential," meaning that if they collapsed, they could cause loss of human life and significant property destruction, according to ASDSO. Most were designed more than 50 years ago, and around 2,500 show signs of damage that would collectively take billions to fix.

Not all of these are behemoths like the Hoover Dam; in fact, thousands are small watershed dams designed to prevent flooding, provide drinking water and preserve wildlife habitats.

When they were built in the 1960s and 1970s, these dams posed very little risk to people because few lived nearby. But several decades on, communities have mushroomed around them, meaning a failure could be devastating.

What's more, most of these dams were designed to withstand the environmental conditions that existed when they were built, but global warming and land-use changes have altered the picture.

Some rivers are dwindling due to drought, while others have higher water levels and flows than they did 50 to 60 years ago due to increases in rainfall and urbanization, which reduces the amount of water stored in the soil, Ebrahim Ahmadisharaf, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Florida State University, who was not involved in the research, told Live Science.

Weather is also becoming more extreme and unpredictable, raising the risk of sudden floods, Ahmadisharaf said. In a 2025 study, he and his colleagues found that the likelihood of dam overtopping — when water is so high, it exceeds the capacity of spillways and gushes over the dam — has increased at 33 dams over the past 50 years.

The dams with the highest overtopping probabilities in that study were big dams with relatively large populations living in cities and small towns downstream — including Whitney Dam in Texas, Milford Dam in Kansas and Whiskeytown Dam in California. The population centers that could be impacted include Waco, Texas, with a population of 150,000, and Junction City, Kansas, with 22,000 residents.

"Overtopping is a possible failure mechanism of a dam," Ahmadisharaf explained. "It can lead to catastrophic flooding downstream, and then structural failure. The larger the dam and the shorter the distance to the infrastructure and people downstream, the more dangerous [overtopping is]."

Money problems

One of the biggest hurdles in the way of making dams in the U.S. safer is funding — and the older dams get, the bigger the bill grows.

"Operation, maintenance, and rehabilitation of dams can range in cost from the low thousands to millions of dollars, and responsibility for these expenses lies with owners, many of whom cannot afford these costs," Roche said. "To rehabilitate just the most critical dams was estimated at $37.4 billion, a cost that continues to rise as maintenance, repair, and rehabilitation are delayed."

Rolling out satellite monitoring for dams would increase the financial burden — but it may be worth the cost if it helps prioritize fixes and prevent failures, Roche said. According to a forensic report about the Oroville Dam spillway incident in 2017, which caused more than 180,000 evacuations but no deaths, traditional inspections of dams do not always identify important structural issues.

With only preliminary results available so far, it is hard to tell whether using satellite data to prioritize dam repairs is useful, Roche said. But in theory, "deformation of dam structures may be indicative of a problem or worsening condition," he said.

RELATED STORIES—Dams around the world hold so much water they've shifted Earth's poles, new research shows

—Extreme weather caused more than $100 billion in damage by June — smashing US records

—Baltimore bridge collapse: an engineer explains what happened, and what needs to change

David Bowles, a dam safety risk expert and professor emeritus of civil and environmental engineering at Utah State University, is more skeptical. "There are many ways a dam can breach," Bowles told Live Science in an email. "Foundation settlement is not a major root cause of dam breach in my experience, but it could be a factor particularly if it is not being monitored and managed."

There might also be a role for satellites in assessing dam overtopping risks, Ahmadisharaf said. Satellite radar images could provide better estimates of water levels and flooding, which in turn could help disseminate warnings earlier.

Overall, satellites could provide a broader overview than what we currently have of risks at dams, Ahmadisharaf said. "We can't monitor everywhere," he said, "but satellites provide this opportunity."

TOPICS news analyses Sascha PareSocial Links NavigationStaff writer

Sascha PareSocial Links NavigationStaff writer Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more 18 of Earth's biggest river deltas — including the Nile and Amazon — are sinking faster than global sea levels are rising

18 of Earth's biggest river deltas — including the Nile and Amazon — are sinking faster than global sea levels are rising

Forced closure of premier US weather-modeling institute could endanger millions of Americans

Forced closure of premier US weather-modeling institute could endanger millions of Americans

'Nobody knew why this was happening': Scientists race to understand baffling behavior of 'clumping clouds'

'Nobody knew why this was happening': Scientists race to understand baffling behavior of 'clumping clouds'

Parts of Arizona are being sucked dry, with areas of land sinking 6 inches per year, satellite data reveals

Parts of Arizona are being sucked dry, with areas of land sinking 6 inches per year, satellite data reveals

Enough fresh water is lost from continents each year to meet the needs of 280 million people. Here's how we can combat that.

Enough fresh water is lost from continents each year to meet the needs of 280 million people. Here's how we can combat that.

Californians have been using far less water than suppliers estimated — what does this mean for the state?

Latest in Planet Earth

Californians have been using far less water than suppliers estimated — what does this mean for the state?

Latest in Planet Earth

Critical moment when El Niño started to erode Russia's Arctic sea ice discovered

Critical moment when El Niño started to erode Russia's Arctic sea ice discovered

'Doomsday Clock' ticks 4 seconds closer to midnight

'Doomsday Clock' ticks 4 seconds closer to midnight

Ancient lake full of crop circles lurks in the shadow of Saudi Arabia's 'camel-hump' mountain

Ancient lake full of crop circles lurks in the shadow of Saudi Arabia's 'camel-hump' mountain

A drying climate is making East Africa pull apart faster

A drying climate is making East Africa pull apart faster

Arctic blast probably won't cause trees to explode in the cold — but here's what happens if and when they do go boom

Arctic blast probably won't cause trees to explode in the cold — but here's what happens if and when they do go boom

Chocolate Hills: The color-changing mounds in the Philippines that inspired legends of mud-slinging giants

Latest in News

Chocolate Hills: The color-changing mounds in the Philippines that inspired legends of mud-slinging giants

Latest in News

'Part of the evolutionary fabric of our societies': Same-sex sexual behavior in primates may be a survival strategy, study finds

'Part of the evolutionary fabric of our societies': Same-sex sexual behavior in primates may be a survival strategy, study finds

More than 43,000 years ago, Neanderthals spent centuries collecting animal skulls in a cave; but archaeologists aren't sure why

More than 43,000 years ago, Neanderthals spent centuries collecting animal skulls in a cave; but archaeologists aren't sure why

Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.

Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.

James Webb telescope breaks own record, discovering farthest known galaxy in the universe

James Webb telescope breaks own record, discovering farthest known galaxy in the universe

South Carolina's measles outbreak nears 790 cases — making it the biggest in decades

South Carolina's measles outbreak nears 790 cases — making it the biggest in decades

5,000-year-old rock art from ancient Egypt depicts 'terrifying' conquest of the Sinai Peninsula

LATEST ARTICLES

5,000-year-old rock art from ancient Egypt depicts 'terrifying' conquest of the Sinai Peninsula

LATEST ARTICLES 1More than 43,000 years ago, Neanderthals spent centuries collecting animal skulls in a cave; but archaeologists aren't sure why

1More than 43,000 years ago, Neanderthals spent centuries collecting animal skulls in a cave; but archaeologists aren't sure why- 2Watch awkward Chinese humanoid robot lay it all down on the dance floor

- 3Hawke Frontier ED X 8x42 review

- 4The Snow Moon will 'swallow' one of the brightest stars in the sky this weekend: Where and when to look

- 5Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.