- Chemistry

The complex building blocks of life can form spontaneously in space, a new lab experiment shows.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

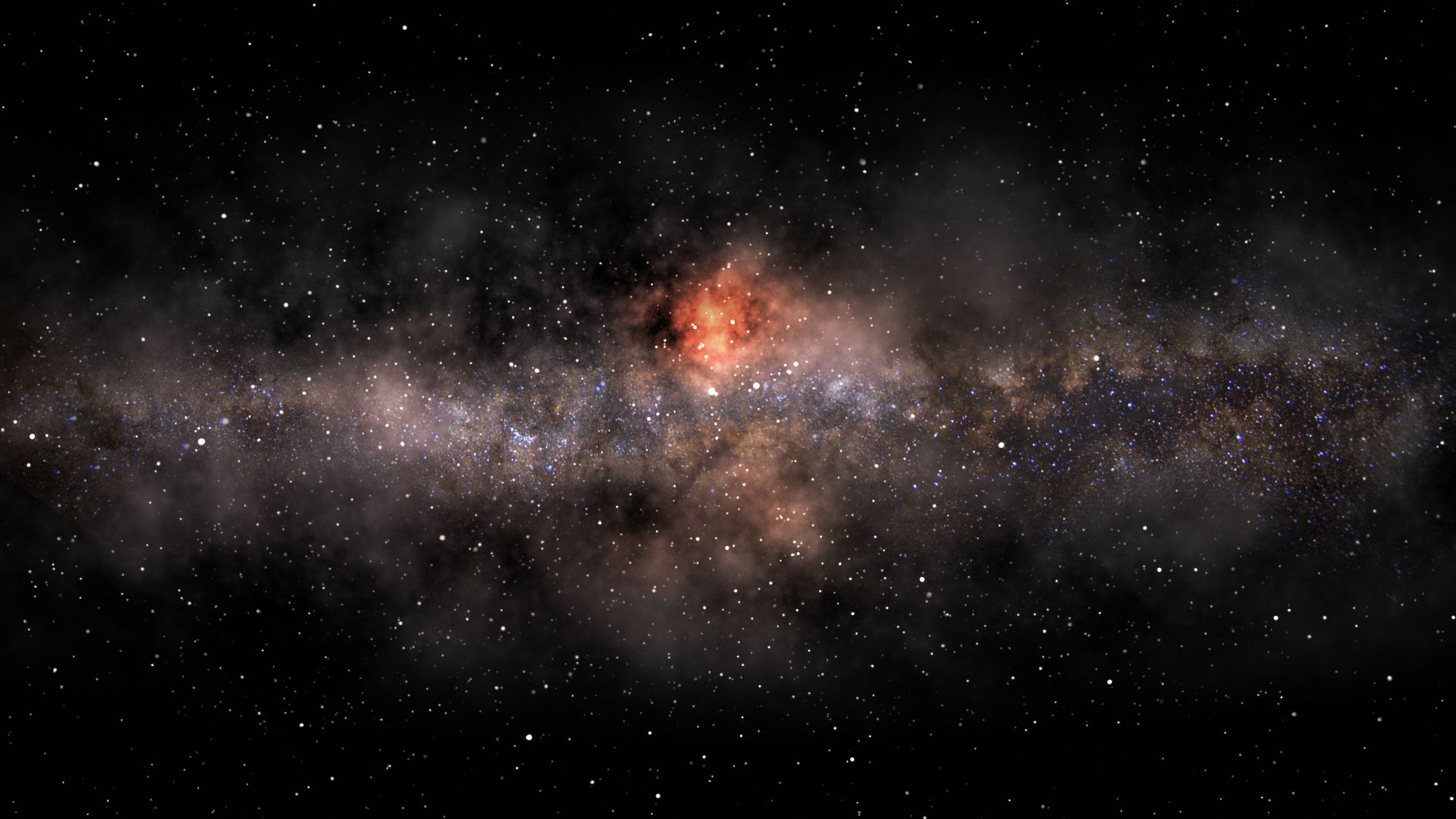

A panoramic view of the Milky Way's dusty center. New research hints that some of the more complicated building blocks of life can form on grains of space dust, potentially leading to biological molecules on planets.

(Image credit: Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

A panoramic view of the Milky Way's dusty center. New research hints that some of the more complicated building blocks of life can form on grains of space dust, potentially leading to biological molecules on planets.

(Image credit: Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

The complex precursors to biological molecules can form spontaneously in interstellar space, according to a lab experiment that opens up new pathways for the origin of life in the universe.

In the presence of ionizing radiation, amino acids — the simplest units of proteins — couple together to form peptide bonds, the first step in the synthesis of more complex biological molecules such as enzymes and cell proteins, according to a new study.

You may like-

Viruses that evolved on the space station and were sent back to Earth were more effective at killing bacteria

Viruses that evolved on the space station and were sent back to Earth were more effective at killing bacteria

-

On Saturn's largest moon, water and oil would mix — opening the door to exotic chemistry in our solar system

On Saturn's largest moon, water and oil would mix — opening the door to exotic chemistry in our solar system

-

'Stop and re-check everything': Scientists discover 26 new bacterial species in NASA's cleanrooms

'Stop and re-check everything': Scientists discover 26 new bacterial species in NASA's cleanrooms

The cocktail of life

Early life evolved from a complex cocktail of prebiotic molecules, including amino acids, basic sugars and RNA. But how these simple starter compounds first formed remains a mystery. One hypothesis proposes that some of these molecules may have originated in outer space and were later delivered to the early Earth through meteorite impacts, said Alfred Hopkinson, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Aarhus University in Denmark.

Glycine, the simplest amino acid, is one example that has been detected in numerous comet and meteorite samples over the past 50 years, including dust samples taken from the asteroid Bennu during NASA’s recent OSIRIS-REx mission. More complex dipeptide units, which are formed when two amino acids bond by releasing water, have not been identified in these extraterrestrial bodies yet, but the intensely ionizing conditions of interstellar space gives rise to unusual chemistry and could theoretically promote the formation of these larger molecules.

"If amino acids could join in space and get to the next level of complexity [dipeptides], when that's delivered to a planetary surface, there's an even more positive starting point to form life," Hopkinson told Live Science. "It's a very exciting theory, and we wanted to see, what is the limit of complexity that these molecules could form in space?"

Remaking the universe in a lab

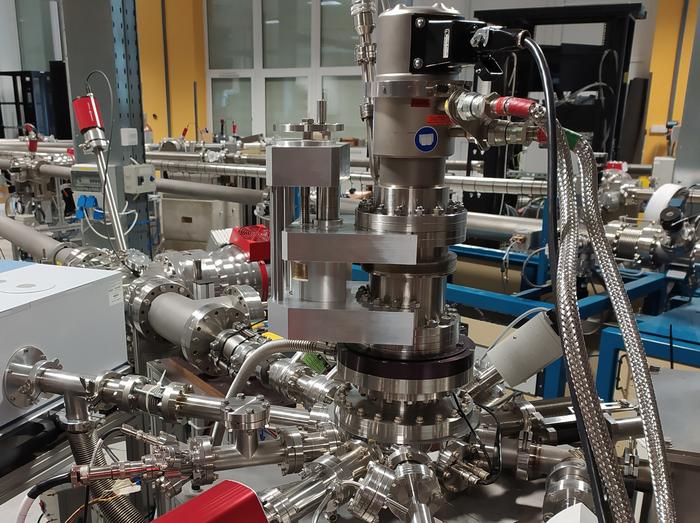

The team, led by Aarhus University astrophysicist Sergio Ioppolo, therefore sought to reproduce the conditions of outer space as closely as possible. Using the HUN-REN Atomki cyclotron facility in Hungary, they bombarded glycine-coated icy crystals with high-energy protons at 20 kelvins (minus 423.67 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 253.15 degrees Celsius) and 10-9 millibar, in order to simulate the conditions of space as closely as possible. Then, using infrared spectroscopy and mass spectrometry — methods of identifying the types of bonds present and the products’ molecular mass, respectively — the researchers analyzed the products as they formed.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.Crucially, though, they used a series of deuterium labels — heavier atoms of hydrogen that produce a different signal during spectroscopic analysis — to track exactly how the glycine molecules were interacting.

Their labeled experiment quickly confirmed their initial hypothesis: The glycine molecules reacted together in the presence of radiation to form a dipeptide called glycylglycine, thus proving that more complex compounds containing peptide bonds could spontaneously form in space.

More chemical surprises

related stories— Building blocks of life may be far more common in space than we thought, study claims

— The building blocks of life can form rapidly around young stars

— Building blocks of life detected in ice outside the Milky Way for first time ever

But dipeptides weren't the only complex organic molecule generated under these conditions. One surprisingly complex signal was tentatively identified as N-formylglycinamide, a subunit of one of the enzymes involved in the production of DNA building blocks and, therefore, another key player in origin-of-life chemistry.

"If you make such a vast array of different types of organic molecules, that could impact the origin of life in ways we hadn't thought of," Hopkinson said. "It's interesting to speak to other researchers — say, RNA world people — and see how that might change their picture of the early Earth."

Going forward, though, the team is investigating whether this same process occurs for other protein-forming amino acids in the interstellar medium, which would potentially open up the possibility of forming more diverse and complex peptides with contrasting chemical properties.

Article SourcesHopkinson, A. T., Wilson, A. M., Pitfield, J., Muiña, A. T., Rácz, R., Mifsud, D. V., Herczku, P., Lakatos, G., Sulik, B., Juhász, Z., Biri, S., McCullough, R. W., Mason, N. J., Scavenius, C., Hornekær, L., & Ioppolo, S. (2026). An interstellar energetic and non-aqueous pathway to peptide formation. Nature Astronomy. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02765-7

Victoria AtkinsonSocial Links NavigationLive Science Contributor

Victoria AtkinsonSocial Links NavigationLive Science ContributorVictoria Atkinson is a freelance science journalist, specializing in chemistry and its interface with the natural and human-made worlds. Currently based in York (UK), she formerly worked as a science content developer at the University of Oxford, and later as a member of the Chemistry World editorial team. Since becoming a freelancer, Victoria has expanded her focus to explore topics from across the sciences and has also worked with Chemistry Review, Neon Squid Publishing and the Open University, amongst others. She has a DPhil in organic chemistry from the University of Oxford.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Viruses that evolved on the space station and were sent back to Earth were more effective at killing bacteria

Viruses that evolved on the space station and were sent back to Earth were more effective at killing bacteria

On Saturn's largest moon, water and oil would mix — opening the door to exotic chemistry in our solar system

On Saturn's largest moon, water and oil would mix — opening the door to exotic chemistry in our solar system

'Stop and re-check everything': Scientists discover 26 new bacterial species in NASA's cleanrooms

'Stop and re-check everything': Scientists discover 26 new bacterial species in NASA's cleanrooms

Scientists put moss on the outside of the International Space Station for 9 months — then kept it growing back on Earth

Scientists put moss on the outside of the International Space Station for 9 months — then kept it growing back on Earth

Advanced alien civilizations could be communicating 'like fireflies' in plain sight, researchers suggest

Advanced alien civilizations could be communicating 'like fireflies' in plain sight, researchers suggest

Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS is erupting in 'ice volcanoes', new images suggest

Latest in Chemistry

Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS is erupting in 'ice volcanoes', new images suggest

Latest in Chemistry

New electrochemical method splits water with electricity to produce hydrogen fuel — and cuts energy costs in the process

New electrochemical method splits water with electricity to produce hydrogen fuel — and cuts energy costs in the process

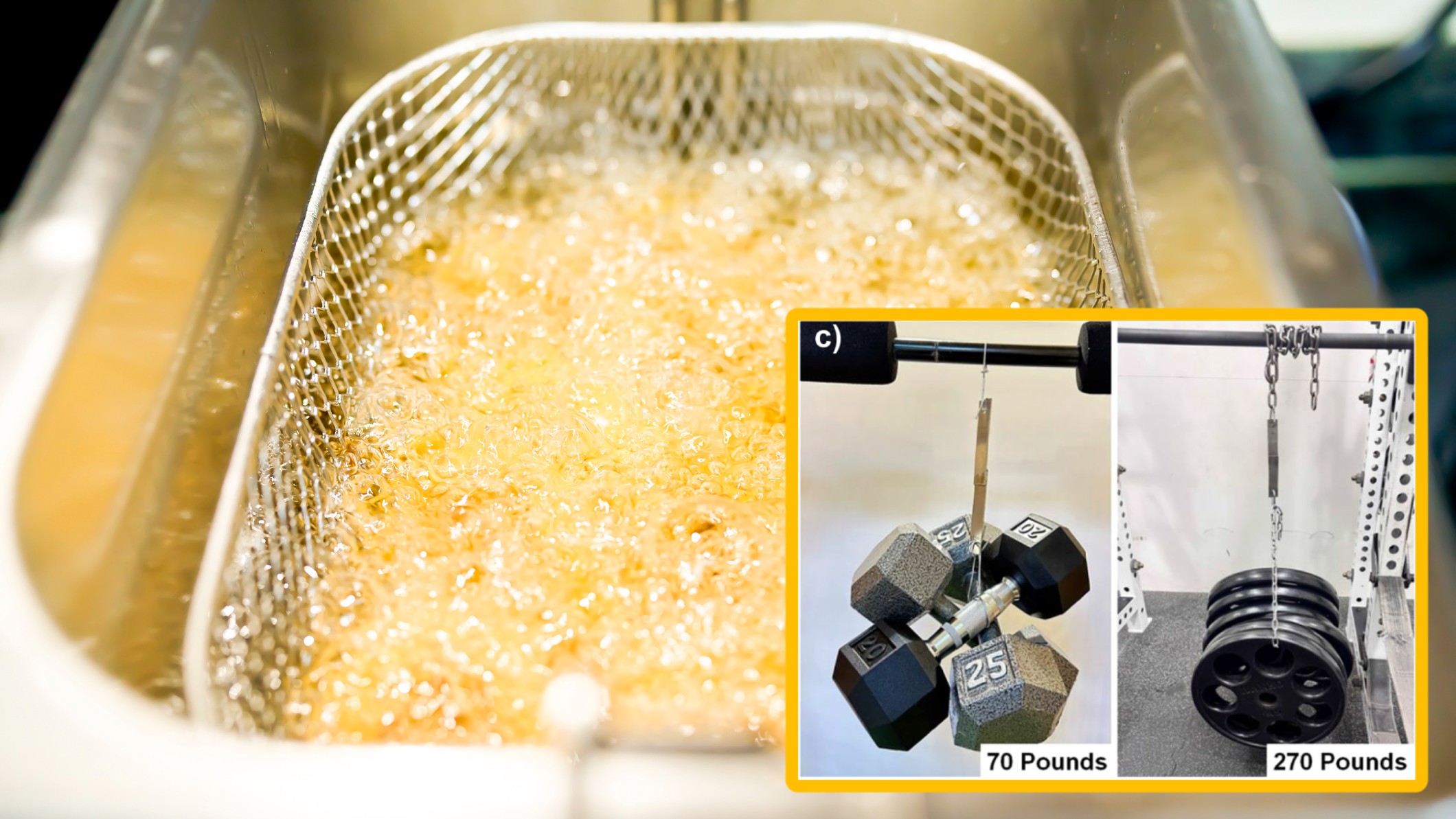

Glue strong enough to tow a car made from used cooking oil

Glue strong enough to tow a car made from used cooking oil

Science history: Chemists discover buckyballs — the most perfect molecules in existence — Nov. 14, 1985

Science history: Chemists discover buckyballs — the most perfect molecules in existence — Nov. 14, 1985

Scientists invent way to use E. coli to create and dye rainbow-colored fabric in the lab

Scientists invent way to use E. coli to create and dye rainbow-colored fabric in the lab

Why does boiling water have bubbles, except in a microwave?

Why does boiling water have bubbles, except in a microwave?

Science history: Scientists use 'click chemistry' to watch molecules in living organisms — Oct. 23, 2007

Latest in News

Science history: Scientists use 'click chemistry' to watch molecules in living organisms — Oct. 23, 2007

Latest in News

Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.

Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.

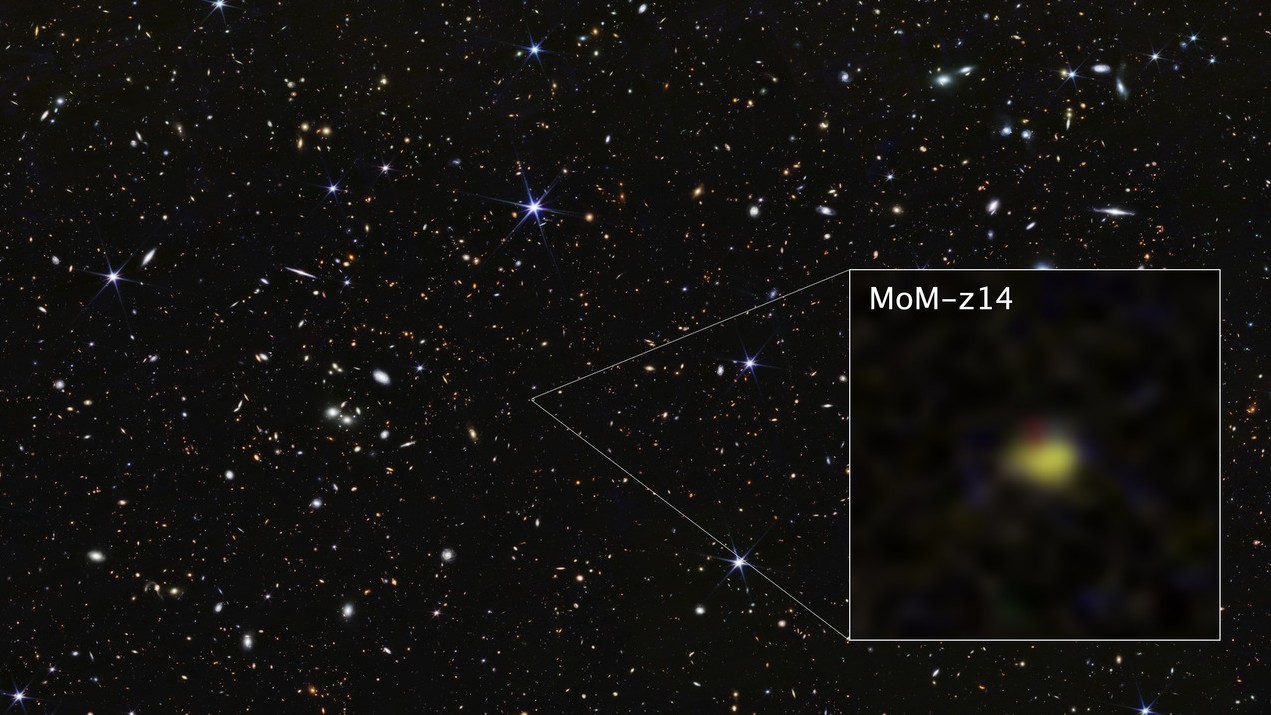

James Webb telescope breaks own record, discovering farthest known galaxy in the universe

James Webb telescope breaks own record, discovering farthest known galaxy in the universe

South Carolina's measles outbreak nears 790 cases — making it the biggest in decades

South Carolina's measles outbreak nears 790 cases — making it the biggest in decades

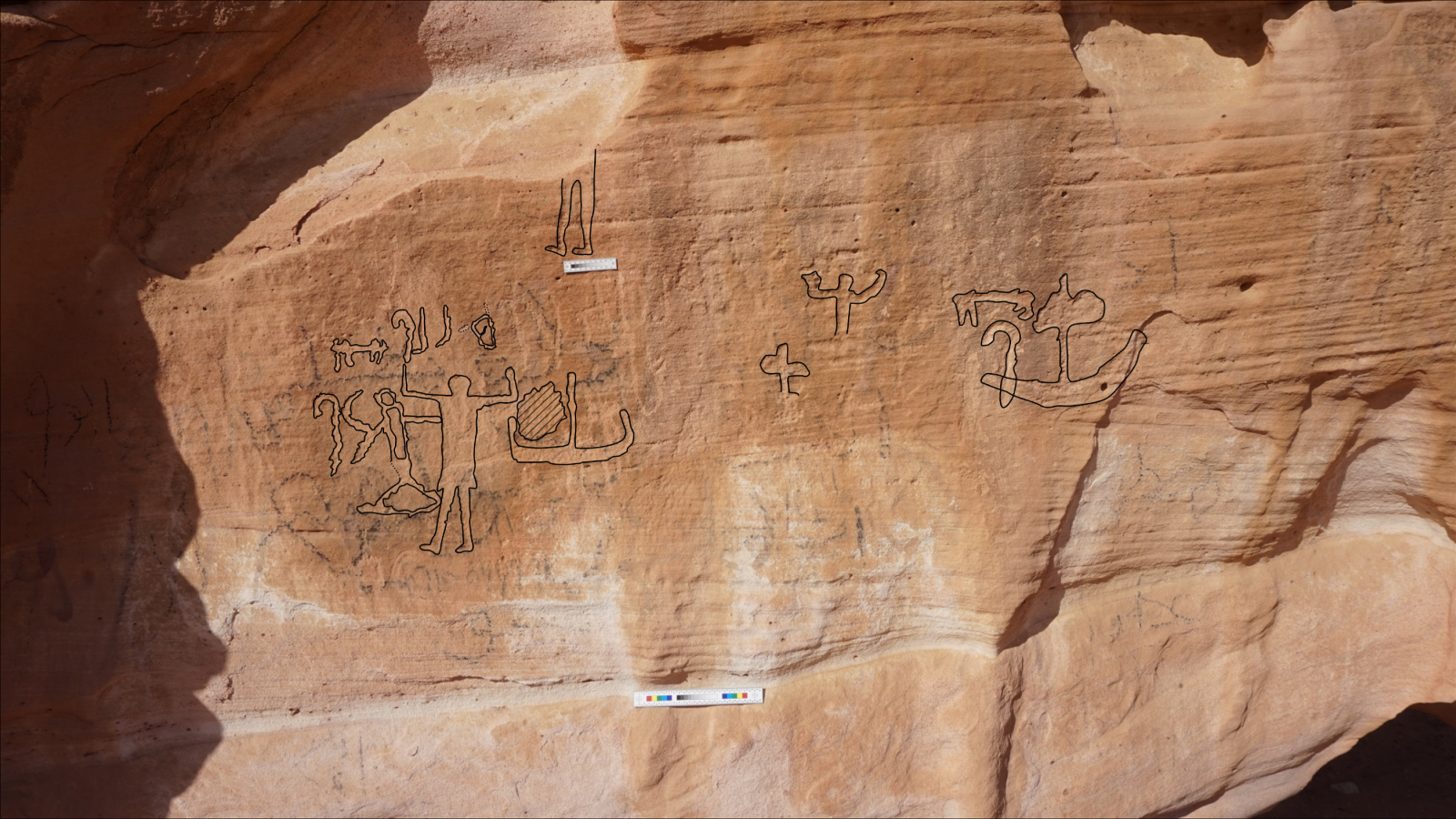

5,000-year-old rock art from ancient Egypt depicts 'terrifying' conquest of the Sinai Peninsula

5,000-year-old rock art from ancient Egypt depicts 'terrifying' conquest of the Sinai Peninsula

Stone Age teenager was mauled by a bear 28,000 years ago, skeletal analysis confirms

Stone Age teenager was mauled by a bear 28,000 years ago, skeletal analysis confirms

NASA jet crashes in flames on Texas runway — taking it out of the Artemis II mission

LATEST ARTICLES

NASA jet crashes in flames on Texas runway — taking it out of the Artemis II mission

LATEST ARTICLES 1Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.

1Halley wasn't the first to figure out the famous comet. An 11th-century monk did it first, new research suggests.- 2'Previously unimaginable': James Webb telescope breaks own record again, discovering farthest known galaxy in the universe

- 3South Carolina's measles outbreak nears 790 cases — making it the biggest in decades

- 450-year-old NASA jet crashes in flames on Texas runway — taking it out of the Artemis II mission

- 55,000-year-old rock art from ancient Egypt depicts 'terrifying' conquest of the Sinai Peninsula