- Animals

- Birds

People searching for honey in Mozambique work with birds via a shared language in a rare case of cooperation between humans and wild animals. This language also comes with regional dialects — that appear to be driven by the birds.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

Honey-harvest in the Niassa Special Reserve, Mozambique.

(Image credit: Claire Spottiswoode)

Honey-harvest in the Niassa Special Reserve, Mozambique.

(Image credit: Claire Spottiswoode)

- Copy link

- X

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Become a Member in Seconds

Unlock instant access to exclusive member features.

Contact me with news and offers from other Future brands Receive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsors By submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Signup +

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Signup +

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Signup +

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Signup +

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Signup +

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Signup +Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Explore An account already exists for this email address, please log in. Subscribe to our newsletterPeople who hunt for honey in Mozambique use distinct dialects when communicating with birds to find bees, and the coordination benefits both species, new research shows.

The interaction is one of the few known examples of human-wildlife cooperation, researchers reported in a study published in the journal People and Nature.

You may like-

Human trash is 'kick-starting' the domestication of city-dwelling raccoons, study suggests

Human trash is 'kick-starting' the domestication of city-dwelling raccoons, study suggests

-

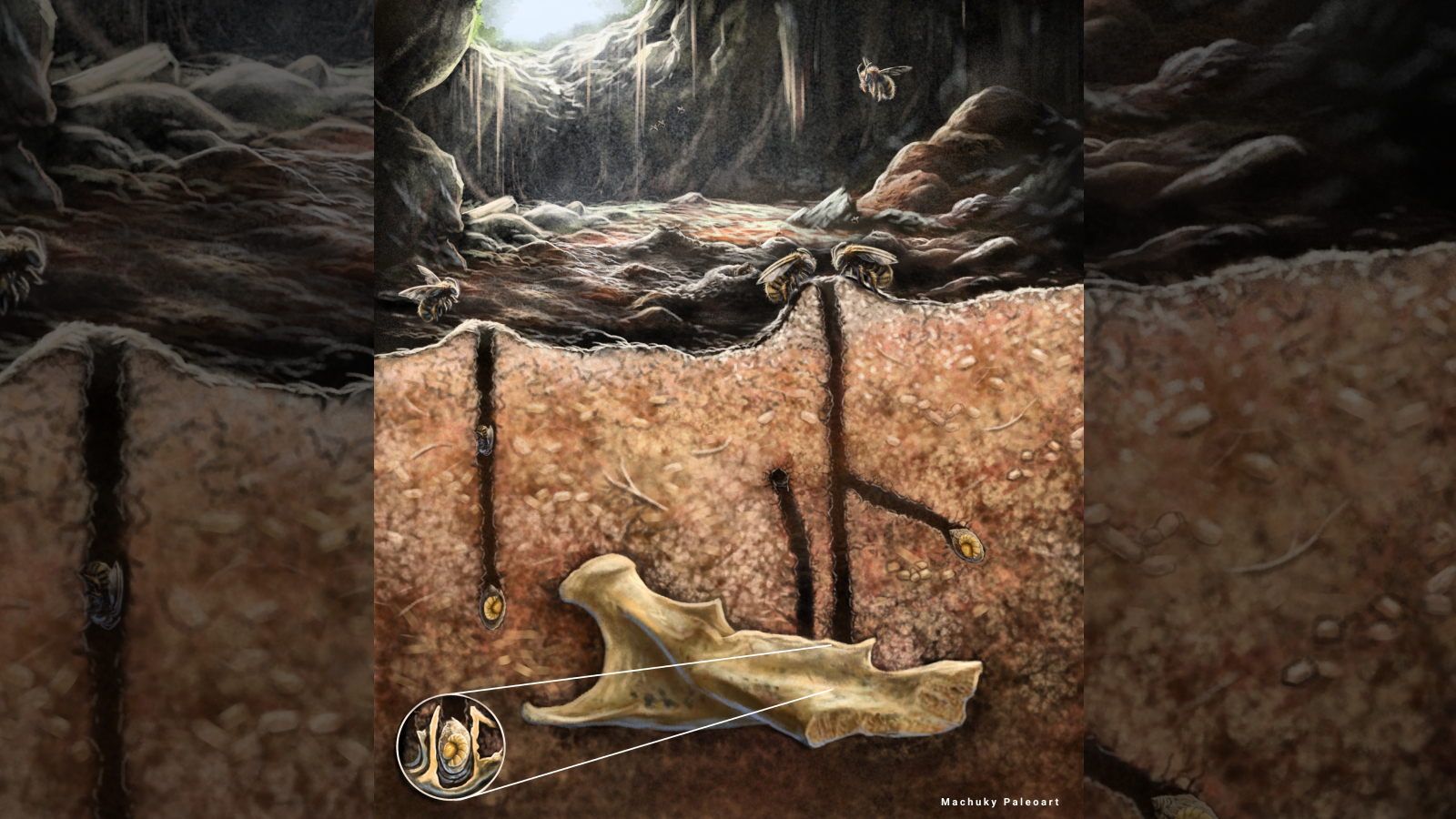

Ancient burrowing bees made their nests in the tooth cavities and vertebrae of dead rodents, scientists discover

Ancient burrowing bees made their nests in the tooth cavities and vertebrae of dead rodents, scientists discover

-

Last of its kind dodo relative spotted in a remote Samoan rainforest

Last of its kind dodo relative spotted in a remote Samoan rainforest

The human hunter summons the bird with a call, and the bird responds with a signal of its own and guides the hunter to the honey.

The relationship works for both species. Humans discover the honey nest, subdue the bees with fire, and break their nest open to access the honey. Meanwhile, the birds eat the leftover wax and larvae — and do not get stung to death by the bees.

"There is active coordination to mutually benefit humans and a wild animal," lead author Jessica van der Wal, a behavioral ecologist at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, told Live Science.

Honey hunters in different parts of Africa have distinct ways of communicating with honeyguides, and van der Wal and colleagues wanted to find out whether their signals also varied within the same area.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.

The international team recorded calls from 131 honey hunters across 13 villages in northern Mozambique's Niassa Special Reserve, where the Yao people depend on wild honey and honeyguides for their livelihoods.

They found that the hunters' trills, grunts, whoops and whistles varied with distance between the villages, irrespective of the habitat. Interestingly, honey hunters who moved into a village adopted the local dialect.

It's "like a different pronunciation," van der Wal. "There is one language that they use with the birds, but there are different dialects."

You may like-

Human trash is 'kick-starting' the domestication of city-dwelling raccoons, study suggests

Human trash is 'kick-starting' the domestication of city-dwelling raccoons, study suggests

-

Ancient burrowing bees made their nests in the tooth cavities and vertebrae of dead rodents, scientists discover

Ancient burrowing bees made their nests in the tooth cavities and vertebrae of dead rodents, scientists discover

-

Last of its kind dodo relative spotted in a remote Samoan rainforest

Last of its kind dodo relative spotted in a remote Samoan rainforest

The study highlights how cultural we are as a species, van der Wal said. "There are a lot of animals that have culture, but humans are really driven by culture, even in the way that we communicate with wild, untrained animals," she added.

Diego Gil, a behavioral ecologist at the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Spain who was not involved in the research, told Live Science he was surprised that the calls did not vary among habitats.

"From a human perspective, it is interesting that human immigrants to a new community learn the way that humans of that community interact with the local birds," he said.

The birds may also be reinforcing the local dialects, said Philipp Heeb, a senior researcher at the French National Centre for Scientific Research who was not involved in the study.

"Once honeyguides learn to respond preferentially to local signals, reciprocally this preference should reinforce local consistency in human signals," he said.

The two species have likely been cooperating for hundreds, if not thousands, of years, and by discriminating against unfamiliar honey-hunter calls, the birds could reinforce regional dialects and limit how much they can drift, he said. "The 'selection' pressure exerted by honeyguides might help explain the stability of the mosaic of dialects in human populations."

Honeyguides do not learn the behavior from their parents, van der Wal said. They are brood parasites, which means that they lay their eggs in other birds' nests.

RELATED STORIES—Australian 'trash parrots' have now developed a local 'drinking tradition'

—Ever watched a pet cow pick up a broom and scratch herself with it? You have now

—Wolf stealing underwater crab traps caught on camera for the first time — signalling 'new dimension' in their behavior

"We think that honeyguides learn from other honeyguides interacting with humans," she said, and her group is investigating whether humans and birds are influencing each other's culture.

Van der wal plans to expand upon this research. She currently leads the Pan-African Honeyguide Research Network, which is documenting honeyguide behavior in different countries.

"We're currently combining all the data and expanding into new places," she said. "There's so much variation in the human culture, not only in the signals or the calls being used, but in their practices and interactions with honeyguides."

Article SourcesVan Der Wal, J. E. M., D’Amelio, P. B., Dauda, C., Cram, D. L., Wood, B. M., & Spottiswoode, C. N. (2026). Cooperative human signals to honeyguides form local dialects. People and Nature. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.70234

Sarah WildSocial Links NavigationLive Science Contributor

Sarah WildSocial Links NavigationLive Science ContributorSarah Wild is a British-South African freelance science journalist. She has written about particle physics, cosmology and everything in between. She studied physics, electronics and English literature at Rhodes University, South Africa, and later read for an MSc Medicine in bioethics.

Since she started perpetrating journalism for a living, she's written books, won awards, and run national science desks. Her work has appeared in Nature, Science, Scientific American, and The Observer, among others. In 2017 she won a gold AAAS Kavli for her reporting on forensics in South Africa.

View MoreYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Human trash is 'kick-starting' the domestication of city-dwelling raccoons, study suggests

Human trash is 'kick-starting' the domestication of city-dwelling raccoons, study suggests

Ancient burrowing bees made their nests in the tooth cavities and vertebrae of dead rodents, scientists discover

Ancient burrowing bees made their nests in the tooth cavities and vertebrae of dead rodents, scientists discover

Last of its kind dodo relative spotted in a remote Samoan rainforest

Last of its kind dodo relative spotted in a remote Samoan rainforest

Pumas in Patagonia started feasting on penguins — but now they're behaving strangely, a new study finds

Pumas in Patagonia started feasting on penguins — but now they're behaving strangely, a new study finds

Killer whales are teaming up with dolphins on salmon hunts, study finds — but not everyone agrees

Killer whales are teaming up with dolphins on salmon hunts, study finds — but not everyone agrees

'Part of the evolutionary fabric of our societies': Same-sex sexual behavior in primates may be a survival strategy, study finds

Latest in Birds

'Part of the evolutionary fabric of our societies': Same-sex sexual behavior in primates may be a survival strategy, study finds

Latest in Birds

Rare nocturnal parrots in New Zealand are breeding for the first time in 4 years — here's why

Rare nocturnal parrots in New Zealand are breeding for the first time in 4 years — here's why

Last of its kind dodo relative spotted in a remote Samoan rainforest

Last of its kind dodo relative spotted in a remote Samoan rainforest

Why do vultures circle?

Why do vultures circle?

Fossil of huge penguin that lived 3 million years ago discovered in New Zealand — what happened to it?

Fossil of huge penguin that lived 3 million years ago discovered in New Zealand — what happened to it?

Rare blue-and-green hybrid jay spotted in Texas is offspring of birds whose lineages split 7 million years ago

Rare blue-and-green hybrid jay spotted in Texas is offspring of birds whose lineages split 7 million years ago

'Rare' ancestor reveals how huge flightless birds made it to faraway lands

Latest in News

'Rare' ancestor reveals how huge flightless birds made it to faraway lands

Latest in News

Men develop cardiovascular disease 7 years before women

Men develop cardiovascular disease 7 years before women

Asteroid 2024 YR4's collision with the moon could create a flash visible from Earth

Asteroid 2024 YR4's collision with the moon could create a flash visible from Earth

Hydrogen leak derails Artemis II wet rehearsal, pushing launch date back by weeks

Hydrogen leak derails Artemis II wet rehearsal, pushing launch date back by weeks

'System in flux': Scientists reveal what happened when wolves and cougars returned to Yellowstone

'System in flux': Scientists reveal what happened when wolves and cougars returned to Yellowstone

In the search for bees, Mozambique honey hunters and birds share a language with distinct, regional dialects

In the search for bees, Mozambique honey hunters and birds share a language with distinct, regional dialects

'Landmark' elephant bone finding in Spain may be from time of Hannibal's war against Rome

LATEST ARTICLES

'Landmark' elephant bone finding in Spain may be from time of Hannibal's war against Rome

LATEST ARTICLES 1Asteroid 2024 YR4's collision with the moon could create a flash visible from Earth, study finds

1Asteroid 2024 YR4's collision with the moon could create a flash visible from Earth, study finds- 2Men develop cardiovascular disease 7 years before women, study suggests. But why?

- 3Hydrogen leak derails Artemis II wet rehearsal, pushing launch date back by weeks

- 4'Landmark' elephant bone finding in Spain may be from time of Hannibal's war against Rome

- 5Mokoqi Star Projector Night Light review