- Health

- Viruses, Infections & Disease

- Cancer

If proven effective in humans, the vaccine could complement standard therapies for HPV-driven cancer, as well as inform the design of therapeutic vaccines for other diseases.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

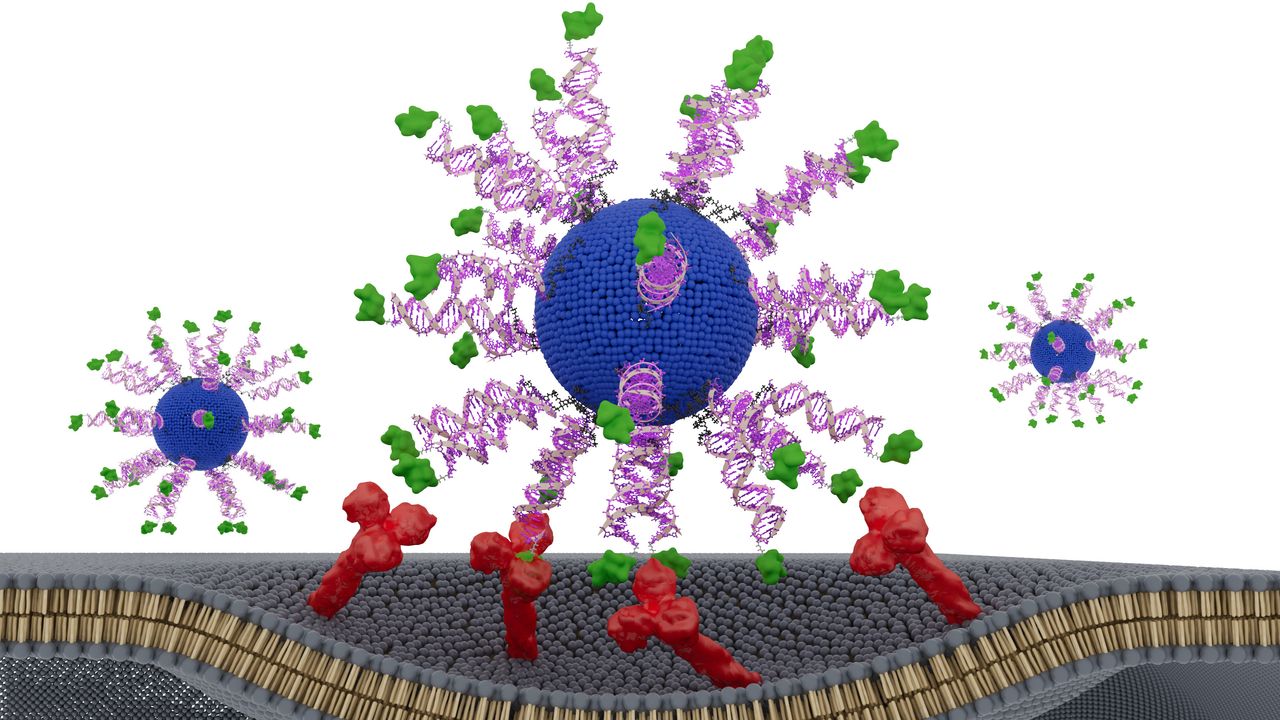

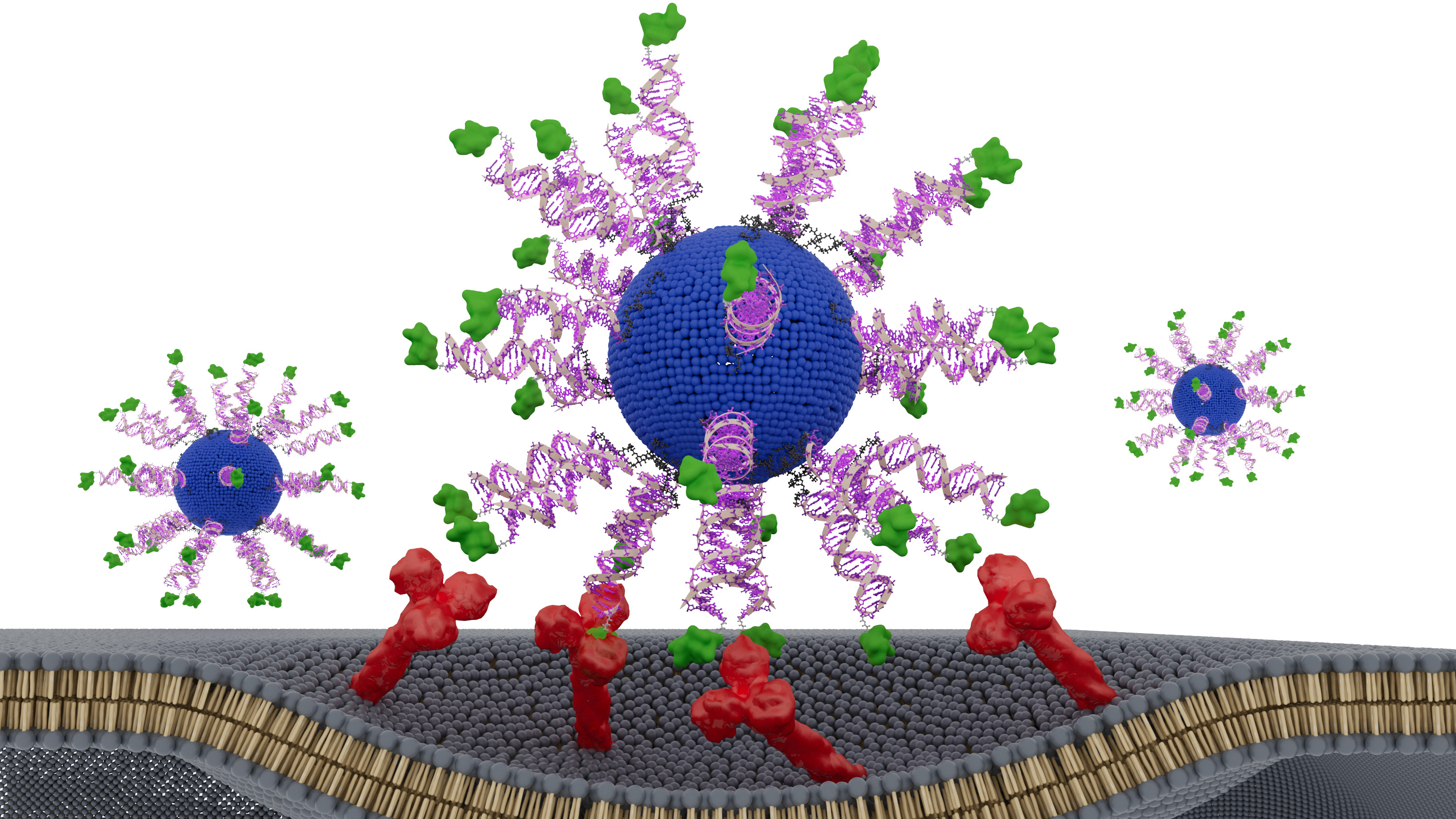

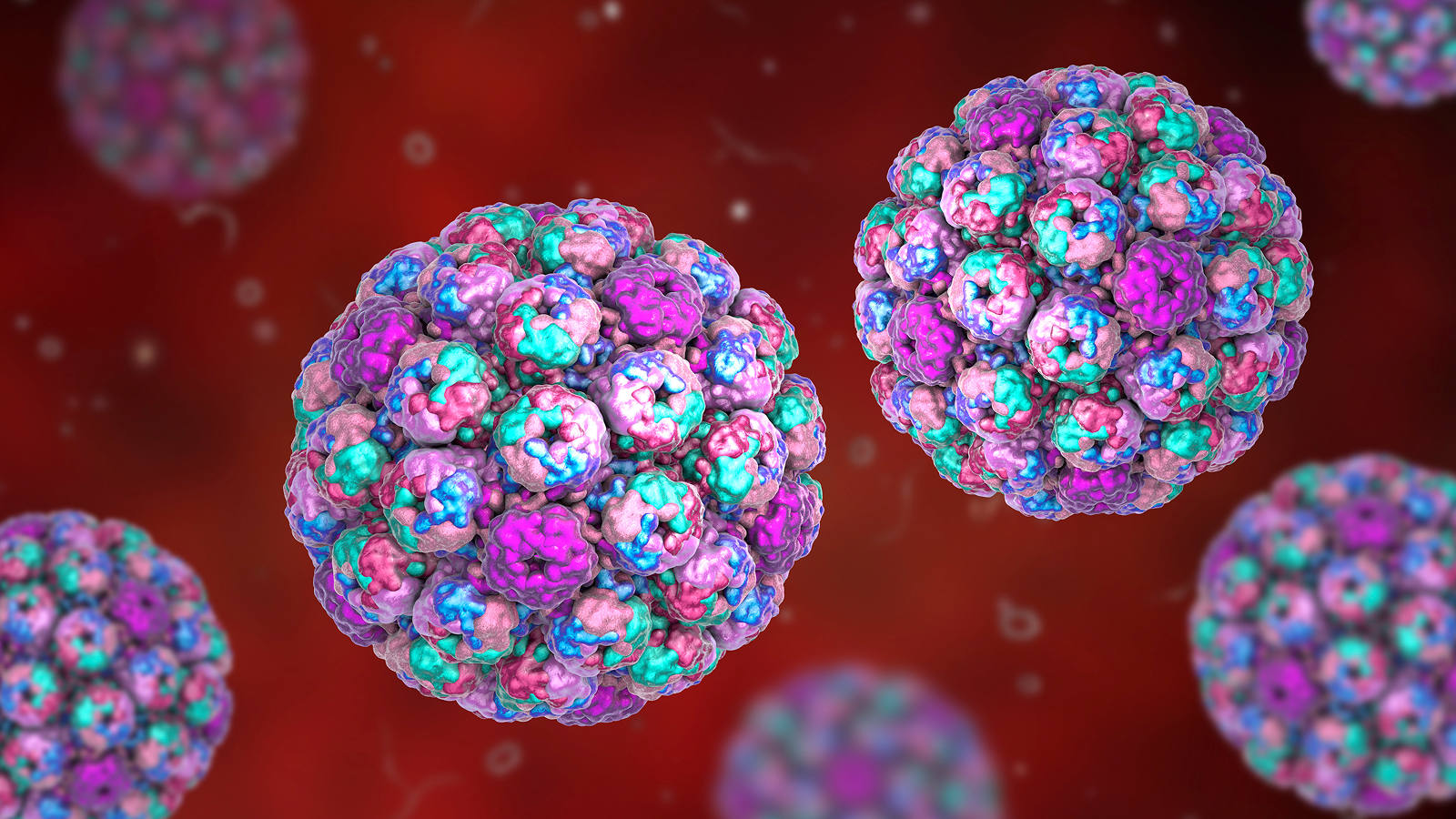

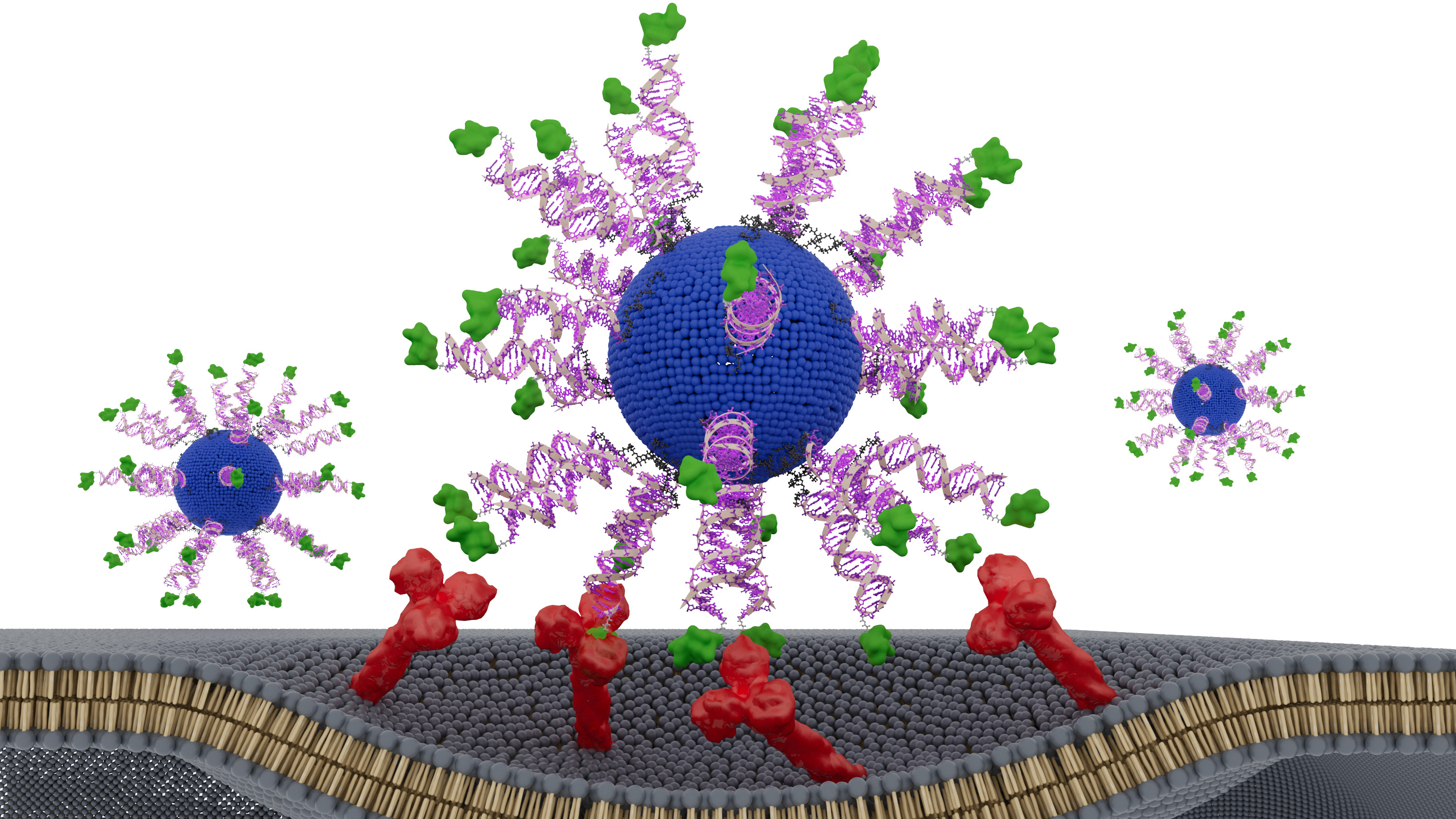

The experimental vaccine is made up of nanoparticles containing an immune-response-triggering substance and protein fragments from the cancer being targeted. In this design, the fragments (purple and green) are arranged so they stick off the nanoparticle surface.

(Image credit: Chad A. Mirkin/Northwestern University)

The experimental vaccine is made up of nanoparticles containing an immune-response-triggering substance and protein fragments from the cancer being targeted. In this design, the fragments (purple and green) are arranged so they stick off the nanoparticle surface.

(Image credit: Chad A. Mirkin/Northwestern University)

- Copy link

- X

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Become a Member in Seconds

Unlock instant access to exclusive member features.

Contact me with news and offers from other Future brands Receive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsors By submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Signup +

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Signup +

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Signup +

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Signup +

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Signup +

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Signup +Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Explore An account already exists for this email address, please log in. Subscribe to our newsletterA vaccine designed to fight HPV-driven head and neck cancers has shown promising results in a lab study in human tissues and mice.

If proven effective in humans, the therapeutic shot could complement standard cancer therapies, and its design may help scientists build better vaccines for other diseases.

You may like-

New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds

New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds

-

A 'functional cure' for HIV may be in reach, early trials suggest

A 'functional cure' for HIV may be in reach, early trials suggest

-

A fentanyl vaccine enters human trials in 2026 — here's how it works

A fentanyl vaccine enters human trials in 2026 — here's how it works

The vaccine Gardasil 9 can prevent HPV infections and thus reduce the risk of these cancers down the line. But for people who already have HPV-related tumors, treatment still relies on surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. Combining a cancer vaccine with these conventional therapies could enhance their effectiveness by teaching the immune system to fight the cancer.

Now, scientists have engineered a cancer vaccine whose components are arranged in a unique structure. Similar to preventive vaccines, cancer vaccines train the immune system to recognize specific proteins — in this case, a protein found on HPV-positive tumors — and often contain ingredients called adjuvants that rev up the immune response. Rather than preventing the disease in the first place, though, cancer vaccines are generally used to treat the disease and help prevent its recurrence.

In lab studies of HPV-positive head and neck cancer, this new, carefully crafted vaccine slowed tumor growth and improved survival in mice, according to a study published Wednesday (Feb. 11) in the journal Science Advances.

Dr. Ezra Cohen, a head and neck cancer specialist at UC San Diego Health who was not involved in the study, said that if the vaccine works in humans, it could complement standard therapies.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over."One can imagine a multi-modality approach to render a patient disease-free and then the vaccine to prevent recurrence," he said. But he cautioned that results in lab animals and isolated tissues don't always translate to humans. "The real test is in people," he told Live Science in an email. "But strong preclinical data, like these, make the chances of success in clinical trials higher."

In this case, the vaccine's underlying design is notable.

"The key finding is that the structure of the vaccine makes a significant difference," Cohen said. "Successful vaccination is not just about selecting the correct antigens [target proteins] but placing those antigens in the right sequence with other vaccine elements."

You may like-

New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds

New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds

-

A 'functional cure' for HIV may be in reach, early trials suggest

A 'functional cure' for HIV may be in reach, early trials suggest

-

A fentanyl vaccine enters human trials in 2026 — here's how it works

A fentanyl vaccine enters human trials in 2026 — here's how it works

The vaccine uses spherical nucleic acids (SNAs) — globe-shaped DNA particles that enter immune cells and bind to targets more effectively than linear DNA does. Each SNA nanoparticle within the vaccine consists of a fatty core surrounded by an adjuvant and a fragment of an HPV protein from the tumor cells. The adjuvant mimics bacterial DNA and is recognized by the immune system as "foreign."

The researchers tested three designs, changing only how the HPV fragment was positioned. One version hid it inside the nanoparticle, while the other two versions had the HPV fragment on the surface of the particle, attached at different ends of the fragment's structure, known as the N terminus and the C terminus.

The version with the fragment attached to the surface via its N terminus triggered the strongest immune response, the team found. This design led killer T cells — immune cells that destroy infected, damaged and cancerous cells — to produce up to eight times more interferon-gamma, a key antitumor signaling protein. This made them more effective at killing HPV-positive cancer cells.

In mouse models of HPV-positive cancer, the vaccine significantly slowed tumor growth. Additionally, when tested in tumor samples collected from HPV-positive cancer patients, the N-terminus vaccine killed two to three times more cancer cells compared with the other two vaccine designs.

RELATED STORIES—'Universal' cancer vaccine heading to human trials could be useful for 'all forms of cancer'

—New self-swab HPV test is an alternative to Pap smears. Here's how it works.

—HPV vaccination drives cervical cancer rates down in both vaccinated and unvaccinated people

"This effect did not come from adding new ingredients or increasing the dose. It came from presenting the same components in a smarter way," study co-author Dr. Jochen Lorch, the medical oncology director of the Northwestern Medicine Head and Neck Cancer Program, said in a statement.

"The immune system is sensitive to the geometry of molecules," he said. "By optimizing how we attach the antigen to the SNA, the immune cells processed it more efficiently."

Looking ahead, study co-author Chad Mirkin, inventor of SNAs and director of Northwestern's International Institute for Nanotechnology, hopes this approach could help scientists redesign older vaccines that initially seemed promising but failed.

"This approach is poised to change the way we formulate vaccines," Mirkin said in the statement. "We may have passed up perfectly acceptable vaccine components simply because they were in the wrong configurations. We can go back to those and restructure and transform them into potent medicines."

DisclaimerThis article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Article SourcesHwang, J. et al. (2026). E711-19 placement and orientation dictate CD8+ T cell response in structurally defined spherical nucleic acid vaccines. Science Advances, 12(7). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aec3876

Clarissa BrincatLive Science Contributor

Clarissa BrincatLive Science ContributorClarissa Brincat is a freelance writer specializing in health and medical research. After completing an MSc in chemistry, she realized she would rather write about science than do it. She learned how to edit scientific papers in a stint as a chemistry copyeditor, before moving on to a medical writer role at a healthcare company. Writing for doctors and experts has its rewards, but Clarissa wanted to communicate with a wider audience, which naturally led her to freelance health and science writing. Her work has also appeared in Medscape, HealthCentral and Medical News Today.

View MoreYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds

New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds

A 'functional cure' for HIV may be in reach, early trials suggest

A 'functional cure' for HIV may be in reach, early trials suggest

A fentanyl vaccine enters human trials in 2026 — here's how it works

A fentanyl vaccine enters human trials in 2026 — here's how it works

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

An experimental mRNA treatment counters immune cell aging in mice

An experimental mRNA treatment counters immune cell aging in mice

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

Latest in Cancer

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

Latest in Cancer

AI-supported breast cancer screening spots more cancers earlier, landmark trial finds

AI-supported breast cancer screening spots more cancers earlier, landmark trial finds

New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds

New triple-drug treatment stops pancreatic cancer in its tracks, a mouse study finds

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

Latest in News

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

Latest in News

Cancer vaccine shows promise against HPV-related throat tumors in early study

Cancer vaccine shows promise against HPV-related throat tumors in early study

New study favors 'fuzzy' dark matter as the backbone of the universe — contrary to decades of research

New study favors 'fuzzy' dark matter as the backbone of the universe — contrary to decades of research

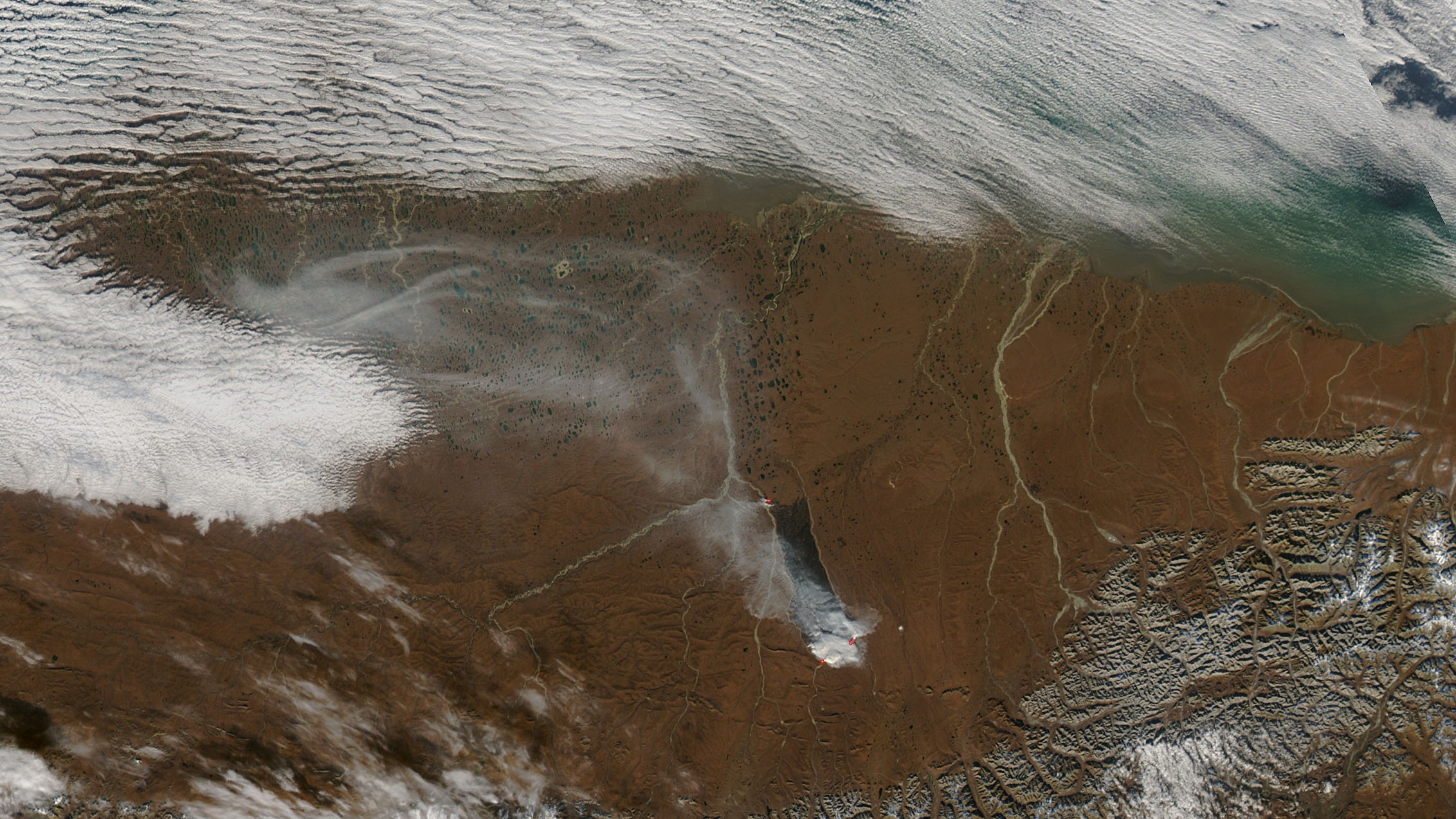

Wildfires in northern Alaska are the worst they've been in 3,000 years

Wildfires in northern Alaska are the worst they've been in 3,000 years

China has planted so many trees around the Taklamakan Desert that it's turned this 'biological void' into a carbon sink

China has planted so many trees around the Taklamakan Desert that it's turned this 'biological void' into a carbon sink

Needle-free insulin? Scientists invent gel that delivers insulin through the skin in animal studies

Needle-free insulin? Scientists invent gel that delivers insulin through the skin in animal studies

Western Europe's earliest known mule died 2,700 years ago — and it was buried with a partially cremated woman

LATEST ARTICLES

Western Europe's earliest known mule died 2,700 years ago — and it was buried with a partially cremated woman

LATEST ARTICLES 1New study favors 'fuzzy' dark matter as the backbone of the universe — contrary to decades of research

1New study favors 'fuzzy' dark matter as the backbone of the universe — contrary to decades of research- 2Wildfires in northern Alaska are the worst they've been in 3,000 years

- 3World's oldest known sewn clothing may be stitched pieces of ice age hide unearthed in Oregon cave

- 4Are you a night owl or an early bird?

- 5Save $102 on our fitness experts' recommended choice as the best walking treadmill, now at one of its lowest-ever prices