- Health

- Viruses, Infections & Disease

Near-weightless conditions can mutate genes and alter the physical structures of bacteria and phages, disrupting their normal interactions in ways that could help us treat drug-resistant infections.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

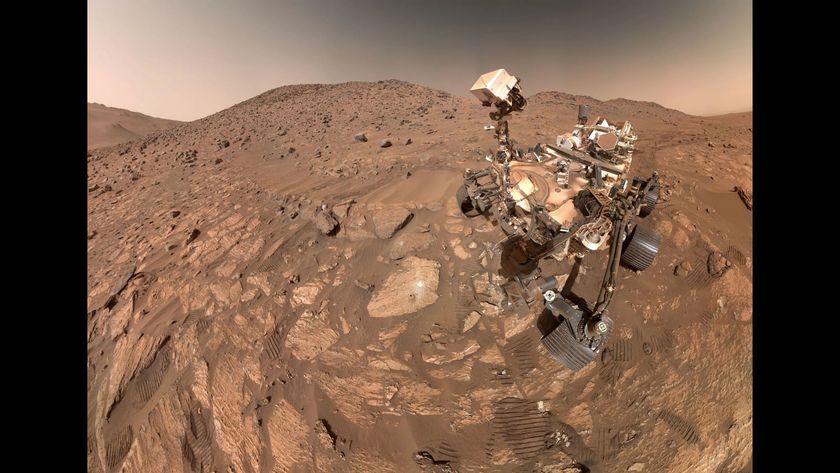

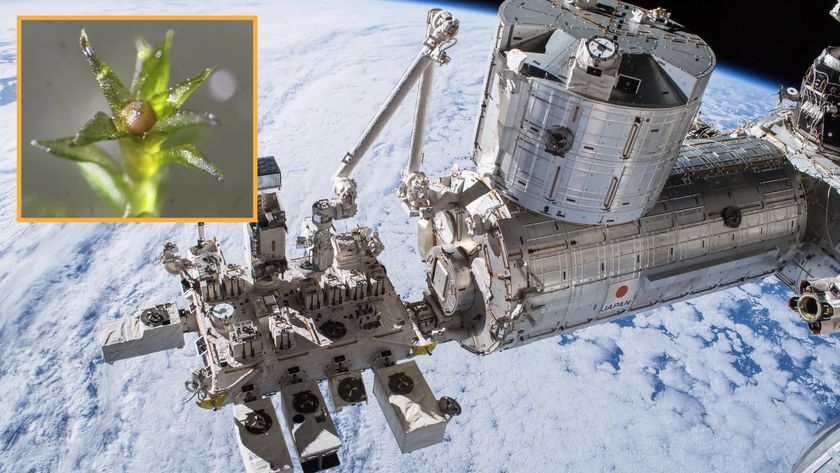

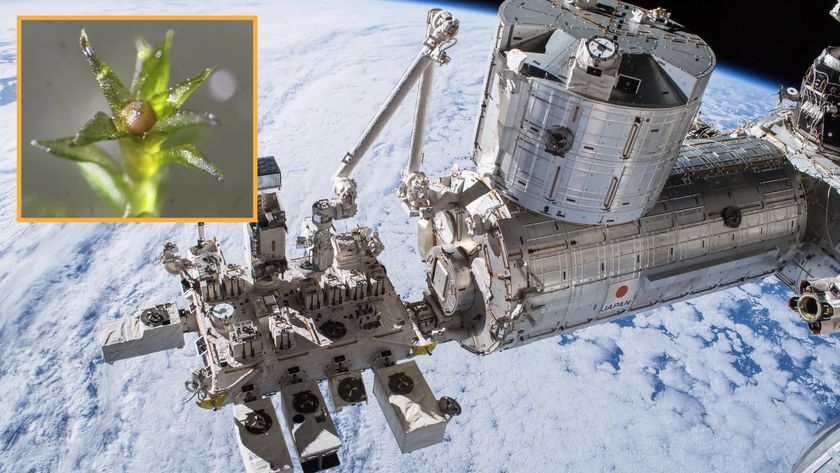

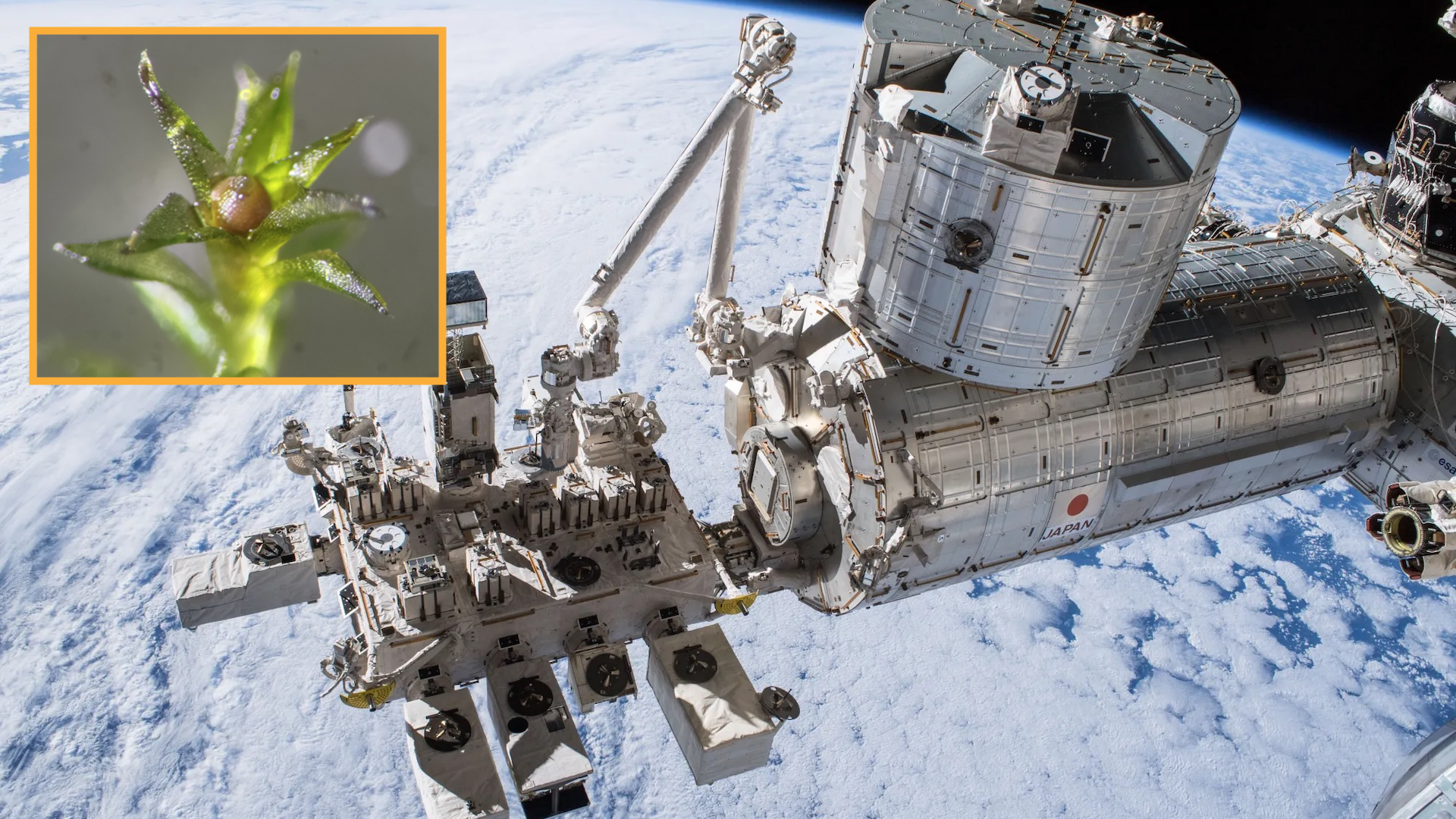

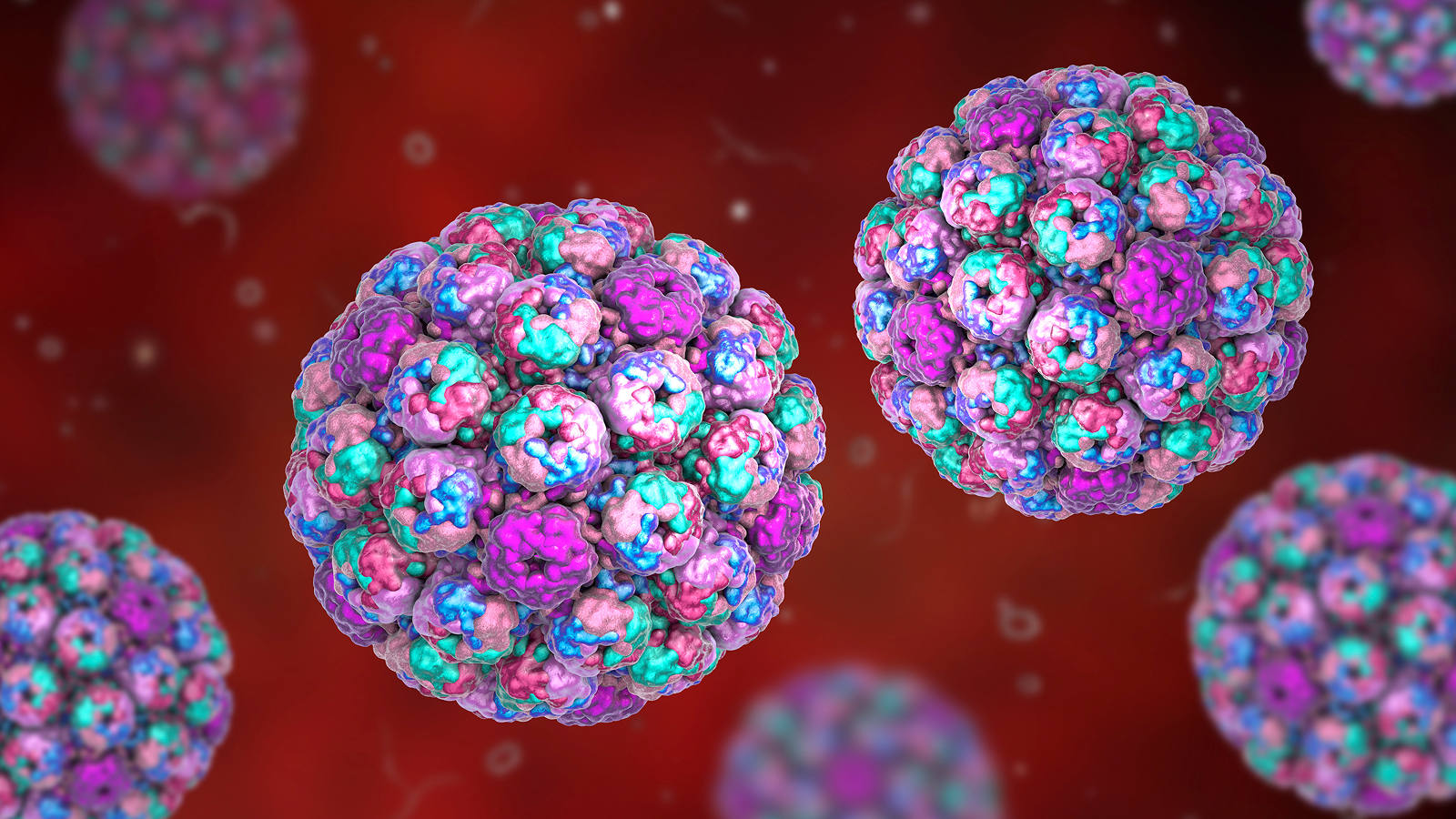

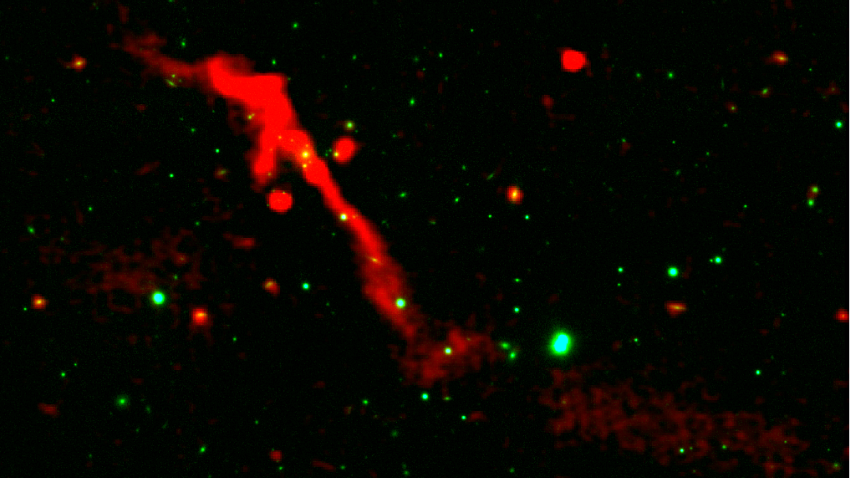

Scientists brought bacteria and phages, meaning viruses that infect bacteria, aboard the ISS to study their evolution.

(Image credit: International space station (dima_zel/Getty Images); E.coli (Shutterstock))

Share

Share by:

Scientists brought bacteria and phages, meaning viruses that infect bacteria, aboard the ISS to study their evolution.

(Image credit: International space station (dima_zel/Getty Images); E.coli (Shutterstock))

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Bacteria and the viruses that infect them, called phages, are locked in an evolutionary arms race. But that evolution follows a different trajectory when the battle takes place in microgravity, a study conducted aboard the International Space Station (ISS) reveals.

As bacteria and phages duke it out, bacteria evolve better defenses to survive while phages evolve new ways to penetrate those defenses. The new study, published Jan. 13 in the journal PLOS Biology, details how that skirmish unfolds in space and reveals insights that could help us design better drugs for antibiotic-resistant bacteria on Earth.

You may like-

'Stop and re-check everything': Scientists discover 26 new bacterial species in NASA's cleanrooms

'Stop and re-check everything': Scientists discover 26 new bacterial species in NASA's cleanrooms

-

Scientists put moss on the outside of the International Space Station for 9 months — then kept it growing back on Earth

Scientists put moss on the outside of the International Space Station for 9 months — then kept it growing back on Earth

-

This is SPARDA: A self-destruct, self-defense system in bacteria that could be a new biotech tool

This is SPARDA: A self-destruct, self-defense system in bacteria that could be a new biotech tool

The analysis of the space-station samples revealed that microgravity fundamentally altered the speed and nature of phage infection.

While the phages could still successfully infect and kill the bacteria in space, the process took longer than it did in the Earth samples. In an earlier study, the same researchers had hypothesized that infection cycles in microgravity would be slower because fluids don't mix as well in microgravity as they do in Earth's gravity.

"This new study validates our hypothesis and expectation," said lead study author Srivatsan Raman, an associate professor in the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

On Earth, the fluids bacteria and viruses exist within are constantly being stirred by gravity — warm water rises, cold water sinks, and heavier particles settle at the bottom. This keeps everything moving and bumping into each other.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.In space, there is no stirring; everything just floats. So because the bacteria and phages weren't bumping into each other as often, phages had to adapt to a much slower pace of life and become more efficient at grabbing onto passing bacteria.

Experts think understanding this alternative form of phage evolution could help them develop new phage therapies. These emerging treatments for infections use phages to kill bacteria or make the germs more vulnerable to traditional antibiotics.

"If we can work out what phages are doing on the genetic level in order to adapt to the microgravity environment, we can apply that knowledge to experiments with resistant bacteria," Nicol Caplin, a former astrobiologist at the European Space Agency who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. "And this can be a positive step in the race to optimise antibiotics on Earth."

You may like-

'Stop and re-check everything': Scientists discover 26 new bacterial species in NASA's cleanrooms

'Stop and re-check everything': Scientists discover 26 new bacterial species in NASA's cleanrooms

-

Scientists put moss on the outside of the International Space Station for 9 months — then kept it growing back on Earth

Scientists put moss on the outside of the International Space Station for 9 months — then kept it growing back on Earth

-

This is SPARDA: A self-destruct, self-defense system in bacteria that could be a new biotech tool

This is SPARDA: A self-destruct, self-defense system in bacteria that could be a new biotech tool

Whole-genome sequencing revealed that both the bacteria and the phages on the ISS accumulated distinctive genetic mutations not observed in the samples on Earth. The space-based viruses accumulated specific mutations that boosted their ability to infect bacteria, as well as their ability to bind to bacterial receptors. Simultaneously, the E. coli developed mutations that protected against the phages' attacks — by tweaking their receptors, for instance — and enhanced their survival in microgravity.

Then, the researchers used a technique called deep mutational scanning to examine the changes in the viruses' receptor-binding proteins. They found that the adaptations driven by the unique cosmic environment may have practical applications back home.

When the phages were transported back to Earth and tested, the space-adapted changes in their receptor-binding protein resulted in increased activity against E. coli strains that commonly cause urinary tract infections. These strains are typically resistant to the T7 phages.

"It was a serendipitous finding," Raman said. "We were not expecting that the [mutant] phages that we identified on the ISS would kill pathogens on Earth."

RELATED STORIES—Antibiotic found hiding in plain sight could treat dangerous infections, early study finds

—How fast can antibiotic resistance evolve?

—Antibiotic resistance makes once-lifesaving drugs useless. Could we reverse it?

"These results show how space can help us improve the activity of phage therapies," said Charlie Mo, an assistant professor in the Department of Bacteriology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who was not involved in the study.

"However," Mo added, "we do have to factor in the cost of sending phages into space or simulating microgravity on Earth to achieve these results."

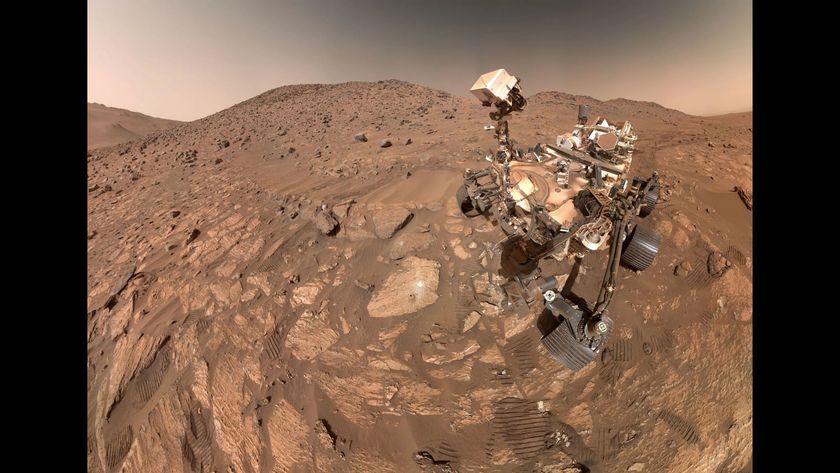

In addition to helping fight infections in Earthbound patients, the research could help yield more effective phage therapies for use in microgravity, Mo suggested. "This could be important for astronauts' health on long-term space missions — for example, missions to the moon or Mars, or prolonged ISS stays."

Manuela CallariLive Science Contributor

Manuela CallariLive Science ContributorManuela Callari is a freelance science journalist specializing in human and planetary health. Her words have been published in MIT Technology Reviews, The Guardian, Medscape, and others.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more 'Stop and re-check everything': Scientists discover 26 new bacterial species in NASA's cleanrooms

'Stop and re-check everything': Scientists discover 26 new bacterial species in NASA's cleanrooms

Scientists put moss on the outside of the International Space Station for 9 months — then kept it growing back on Earth

Scientists put moss on the outside of the International Space Station for 9 months — then kept it growing back on Earth

This is SPARDA: A self-destruct, self-defense system in bacteria that could be a new biotech tool

This is SPARDA: A self-destruct, self-defense system in bacteria that could be a new biotech tool

Metal compounds identified as potential new antibiotics, thanks to robots doing 'click chemistry'

Metal compounds identified as potential new antibiotics, thanks to robots doing 'click chemistry'

That was the week in science: Vaccine skeptics get hep B win | Comet 3I/ATLAS surprises | 'Cold Supermoon' pictures

That was the week in science: Vaccine skeptics get hep B win | Comet 3I/ATLAS surprises | 'Cold Supermoon' pictures

That was the week in science: Second earthquake hits Japan | Geminids to peak | NASA loses contact with Mars probe

Latest in Viruses, Infections & Disease

That was the week in science: Second earthquake hits Japan | Geminids to peak | NASA loses contact with Mars probe

Latest in Viruses, Infections & Disease

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

Color blindness linked to lower bladder cancer survival, early study hints

Why is flu season so bad this year?

Why is flu season so bad this year?

It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

It matters what time of day you get cancer treatment, study suggests

Man caught rabies from organ transplant after donor was scratched by skunk

Man caught rabies from organ transplant after donor was scratched by skunk

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

Widespread cold virus you've never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

Latest in News

New tests could nearly halve the rate of late-stage cancers, some scientists say — is that true?

Latest in News

Enormous freshwater reservoir discovered off the East Coast may be 20,000 years old and big enough to supply NYC for 800 years

Enormous freshwater reservoir discovered off the East Coast may be 20,000 years old and big enough to supply NYC for 800 years

2.6 million-year-old jaw from extinct 'Nutcracker Man' is found where we didn't expect it

2.6 million-year-old jaw from extinct 'Nutcracker Man' is found where we didn't expect it

Early research hints at why women experience more severe gut pain than men do

Early research hints at why women experience more severe gut pain than men do

Scientists see monster black hole 'reborn' after 100 million years of rest

Scientists see monster black hole 'reborn' after 100 million years of rest

Tiny improvements in sleep, nutrition and exercise could significantly extend lifespan, study suggests

Tiny improvements in sleep, nutrition and exercise could significantly extend lifespan, study suggests

Earth hit by biggest 'solar radiation storm' in 23 years, triggering Northern Lights as far as Southern California

LATEST ARTICLES

Earth hit by biggest 'solar radiation storm' in 23 years, triggering Northern Lights as far as Southern California

LATEST ARTICLES 12.6 million-year-old jaw from extinct 'Nutcracker Man' is found where we didn't expect it

12.6 million-year-old jaw from extinct 'Nutcracker Man' is found where we didn't expect it- 2World's oldest known rock art predates modern humans' entrance into Europe — and it was found in an Indonesian cave

- 3Bring the Northern Lights indoors with this Amazon deal on one of our top-rated star projectors

- 4Save $99 on the 2024 edition of Apple's impressive AirPods Max headphones

- 5Hommkiety Galaxy star projector review — a budget best buy