- Archaeology

A new analysis of mineral grains has refuted the "glacial transport theory" that suggests Stonehenge's bluestones and Altar Stone were delivered to Salisbury Plain by glaciers.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

Stonehenge's megaliths were not transported by glaciers to their current location, researchers say.

(Image credit: Captain Skyhigh via Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

Stonehenge's megaliths were not transported by glaciers to their current location, researchers say.

(Image credit: Captain Skyhigh via Getty Images)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Humans — not glaciers — transported Stonehenge's megaliths across Great Britain to their current location in southern England, a new study confirms.

Scientists have believed for decades that the 5,000-year-old monument's iconic stones came from what is now Wales and even as far as Scotland, but there is still debate as to how the stones arrived at Salisbury Plain in southern England.

You may like-

18,000 years ago, ice age humans built dwellings out of mammoth bones in Ukraine

18,000 years ago, ice age humans built dwellings out of mammoth bones in Ukraine

-

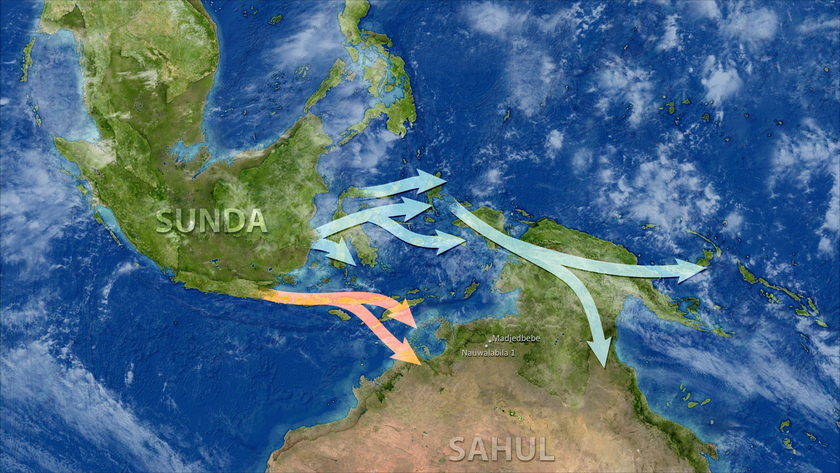

Modern humans arrived in Australia 60,000 years ago and may have interbred with archaic humans such as 'hobbits'

Modern humans arrived in Australia 60,000 years ago and may have interbred with archaic humans such as 'hobbits'

-

Indigenous Americans dragged, carried or floated 5-ton tree more than 100 miles to North America's largest city north of Mexico 900 years ago

Indigenous Americans dragged, carried or floated 5-ton tree more than 100 miles to North America's largest city north of Mexico 900 years ago

"While previous research had cast doubt on the glacial transport theory, our study goes further and applies cutting-edge mineral fingerprinting to trace the stones' true origins," study authors Anthony Clarke, a research geologist at Curtin University in Australia, and Christopher Kirkland, a professor of geology also at Curtin University, wrote in The Conversation.

Stonehenge's bluestones, so called because they acquire a bluish tinge when wet or freshly broken, are from the Preseli Hills in western Wales, meaning people likely dragged them 140 miles (225 kilometers) to the site of the prehistoric monument. More remarkable still, researchers think the Altar Stone inside Stonehenge's middle circle came from northern England or Scotland, which is much farther away — at least 300 miles (500 km) — from Salisbury Plain and may have required boats.

The glacial transport theory is a counterproposal to the idea that people moved the stones from elsewhere in the U.K. to build the monument on Salisbury Plain, instead using stones that had already been transported there by natural means. However, as Stonehenge’s rocks show no signs of glacial transport, and the southern extent of Great Britain’s former ice sheets remain unclear, archaeologists have disputed the idea.

To investigate further, the researchers behind the new study used known radioactive decay rates to date tiny specks of zircon and apatite minerals left over from ancient rocks in river sediments around Stonehenge. The age of these specks reveals the age of rocks that once existed in the region, which, in turn, can provide information about where these rocks came from.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.Different rock formations have different ages, so if the rocks that became parts of Stonehenge were dragged across the land by glaciers, they would have left these tiny traces around Salisbury Plain that could then be matched with rocks in their original locations.

RELATED STORIES—Stonehenge isn't the oldest monument of its kind in England, study reveals

—Was Stonehenge an ancient calendar? A new study says no.

—Why was Stonehenge built?

The researchers analyzed more than 700 zircon and apatite grains but found no significant match for rocks in either western Wales or Scotland. Instead, most of the zircon grains studied showed dates between 1.7 billion and 1.1 billion years ago, coinciding with a time when much of what is now southern England was covered in compacted sand, the researchers wrote in The Conversation. On the other hand, the ages of apatite grains converged around 60 million years ago, when southern England was a shallow, subtropical sea. This means the minerals in rivers around Stonehenge are the remnants of rocks from the local area, and hadn’t been swept in from other places.

The results suggest glaciers didn't extend as far south as Salisbury Plain during the last ice age, excluding the possibility that ice sheets dropped off the megaliths of Stonehenge for ancient builders to subsequently use.

"This gives us further evidence the monument's most exotic stones did not arrive by chance but were instead deliberately selected and transported," the researchers wrote.

Article SourcesClarke, A. J. I., & Kirkland, C. L. (2026). Detrital zircon–apatite fingerprinting challenges glacial transport of Stonehenge’s megaliths. Communications Earth & Environment, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03105

Stonehenge quiz: What do you know about the ancient monument?

Sascha PareSocial Links NavigationStaff writer

Sascha PareSocial Links NavigationStaff writer Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more 18,000 years ago, ice age humans built dwellings out of mammoth bones in Ukraine

18,000 years ago, ice age humans built dwellings out of mammoth bones in Ukraine

Modern humans arrived in Australia 60,000 years ago and may have interbred with archaic humans such as 'hobbits'

Modern humans arrived in Australia 60,000 years ago and may have interbred with archaic humans such as 'hobbits'

Indigenous Americans dragged, carried or floated 5-ton tree more than 100 miles to North America's largest city north of Mexico 900 years ago

Indigenous Americans dragged, carried or floated 5-ton tree more than 100 miles to North America's largest city north of Mexico 900 years ago

3,300-year-old cremations found in Scotland suggest the people died in a mysterious catastrophic event

3,300-year-old cremations found in Scotland suggest the people died in a mysterious catastrophic event

Massive 3,000-year-old Maya site in Mexico depicts the cosmos and the 'order of the universe,' study claims

Massive 3,000-year-old Maya site in Mexico depicts the cosmos and the 'order of the universe,' study claims

The Bering Land Bridge has been submerged since the last ice age. Will scientists ever study it?

Latest in Archaeology

The Bering Land Bridge has been submerged since the last ice age. Will scientists ever study it?

Latest in Archaeology

Some of the oldest harpoons ever found reveal Indigenous people in Brazil were hunting whales 5,000 years ago

Some of the oldest harpoons ever found reveal Indigenous people in Brazil were hunting whales 5,000 years ago

5,500-year-old human skeleton discovered in Colombia holds the oldest evidence yet that syphilis came from the Americas

5,500-year-old human skeleton discovered in Colombia holds the oldest evidence yet that syphilis came from the Americas

2.6 million-year-old jaw from extinct 'Nutcracker Man' is found where we didn't expect it

2.6 million-year-old jaw from extinct 'Nutcracker Man' is found where we didn't expect it

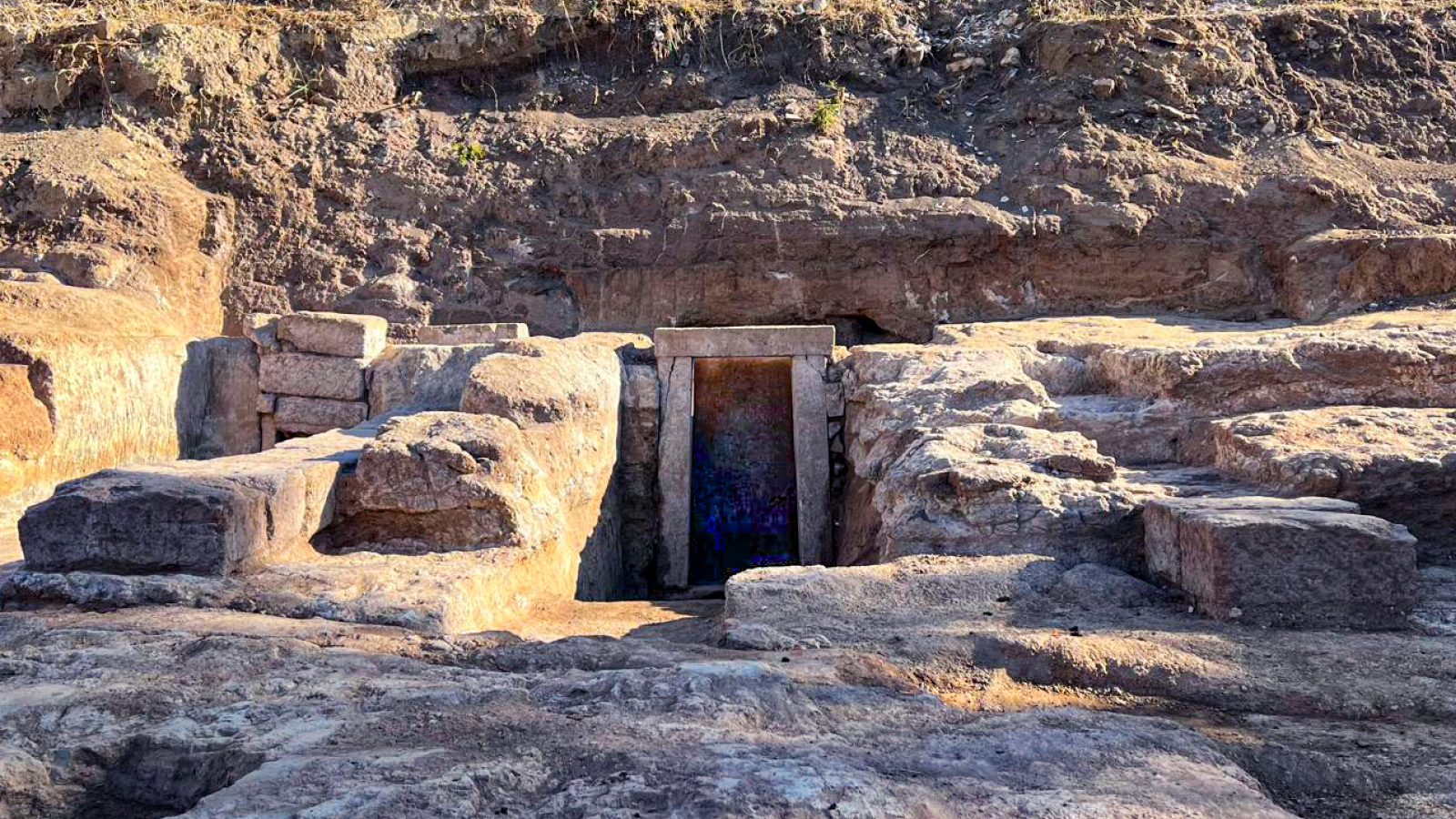

2,400-year-old Hercules shrine and elite tombs discovered outside ancient Rome's walls

2,400-year-old Hercules shrine and elite tombs discovered outside ancient Rome's walls

World's oldest known rock art predates modern humans' entrance into Europe — and it was found in an Indonesian cave

World's oldest known rock art predates modern humans' entrance into Europe — and it was found in an Indonesian cave

Medieval 'super ship' found wrecked off Denmark is largest vessel of its kind

Latest in News

Medieval 'super ship' found wrecked off Denmark is largest vessel of its kind

Latest in News

People, not glaciers, transported rocks to Stonehenge, study confirms

People, not glaciers, transported rocks to Stonehenge, study confirms

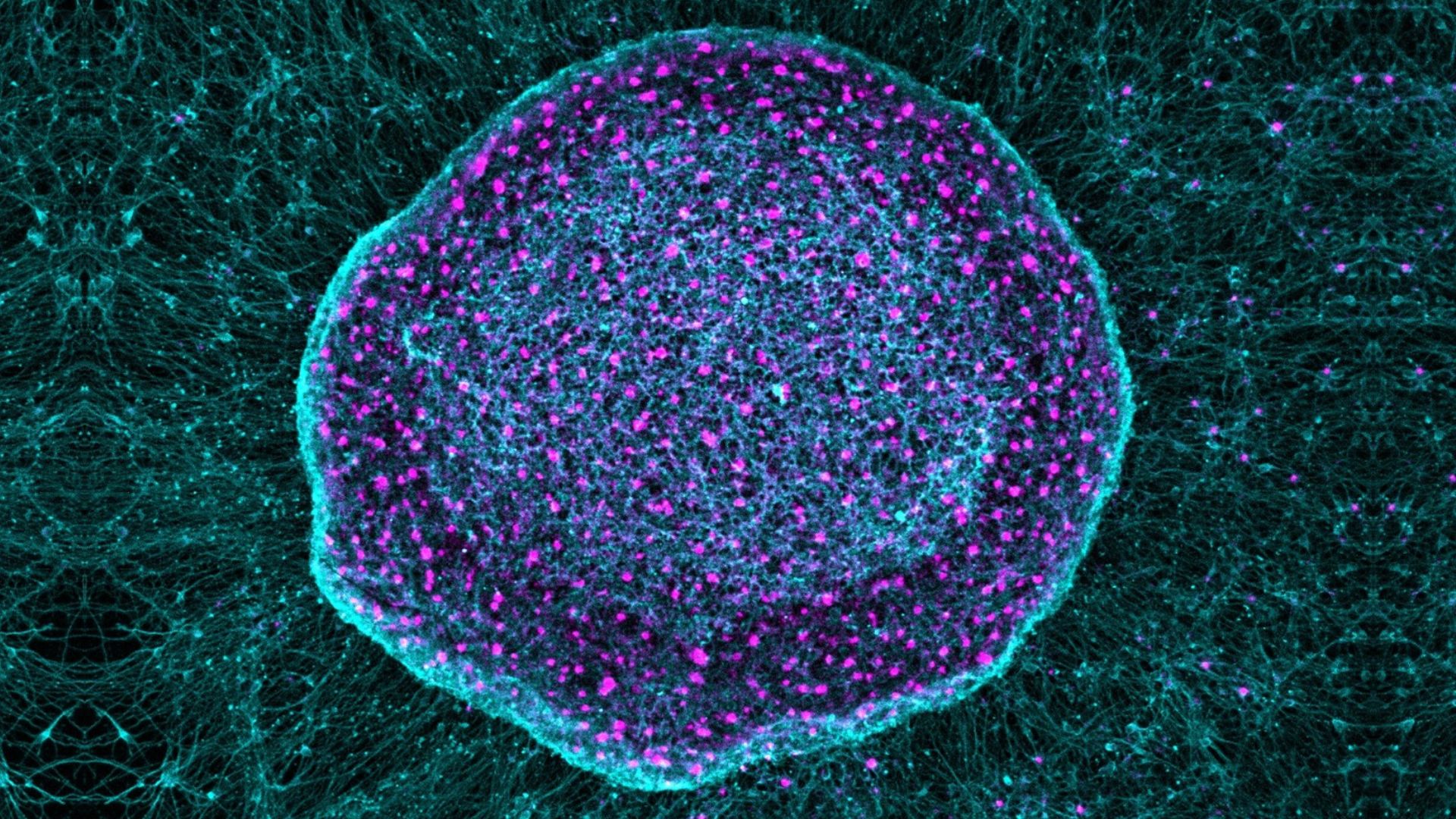

'Pain sponge' derived from stem cells could soak up pain signals before they reach the brain

'Pain sponge' derived from stem cells could soak up pain signals before they reach the brain

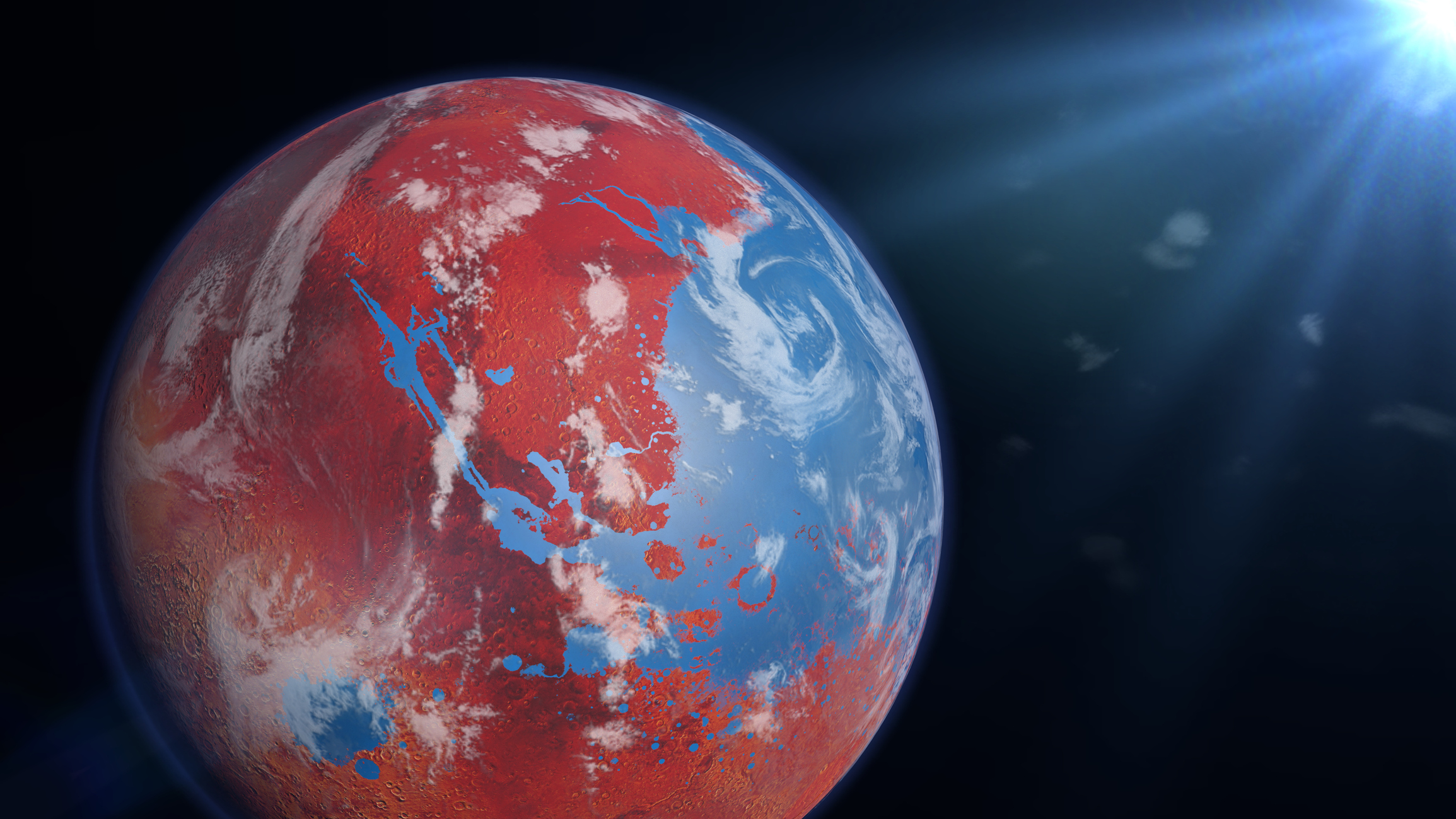

An ocean the size of the Arctic once covered half of Mars, new images hint

An ocean the size of the Arctic once covered half of Mars, new images hint

Arctic blast probably won't cause trees to explode in the cold — but here's what happens if and when they do go boom

Arctic blast probably won't cause trees to explode in the cold — but here's what happens if and when they do go boom

Wegovy now comes in pill form — here's how it works

Wegovy now comes in pill form — here's how it works

'Earthquake on a chip' uses 'phonon' lasers to make mobile devices more efficient

LATEST ARTICLES

'Earthquake on a chip' uses 'phonon' lasers to make mobile devices more efficient

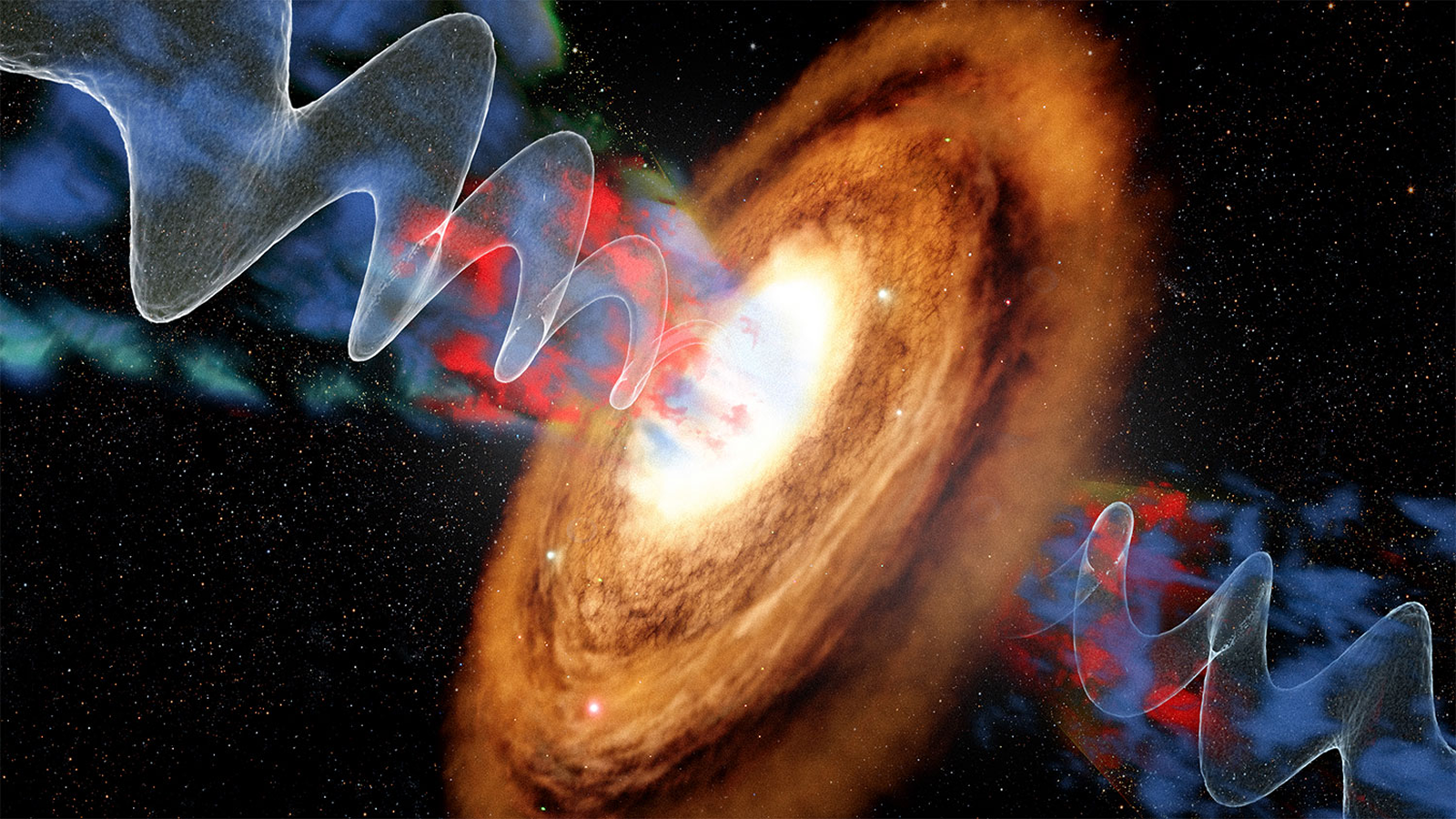

LATEST ARTICLES 1Astronomers discover a gigantic, wobbling black hole jet that 'changes the way we think about the galaxy'

1Astronomers discover a gigantic, wobbling black hole jet that 'changes the way we think about the galaxy'- 2Some of the oldest harpoons ever found reveal Indigenous people in Brazil were hunting whales 5,000 years ago

- 3'A real revolution': The James Webb telescope is upending our understanding of the biggest, oldest black holes in the universe

- 4'Earthquake on a chip' uses 'phonon' lasers to make mobile devices more efficient

- 5Chocolate Hills: The color-changing mounds in the Philippines that inspired legends of mud-slinging giants