- Planet Earth

- Geology

Millions of years ago, the Green River carved a path through the Uinta Mountains instead of flowing around the formation. Now, researchers have discovered how this could have happened.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

For decades, geologists have struggled to understand the Green River's course through the Uinta Mountains in Utah and Colorado.

(Image credit: Susan E. Degginger via Alamy)

Share by:

For decades, geologists have struggled to understand the Green River's course through the Uinta Mountains in Utah and Colorado.

(Image credit: Susan E. Degginger via Alamy)

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Geologists may have finally solved a longstanding mystery surrounding the Colorado River's largest tributary, which appears to have defied gravity and flowed uphill when it first formed.

The Green River originates in Wyoming and links up with the Colorado River in Canyonlands National Park in Utah. Around 8 million years ago, the Green River carved its way through the 13,000-foot-tall (4,000 meters) Uinta Mountains in northeastern Utah and northwestern Colorado instead of flowing around the formation. But in a new study, researchers argue this isn't possible without a mechanism to lower the mountains.

You may like-

What's the oldest river in the world?

What's the oldest river in the world?

-

Giant structure discovered deep beneath Bermuda is unlike anything else on Earth

Giant structure discovered deep beneath Bermuda is unlike anything else on Earth

-

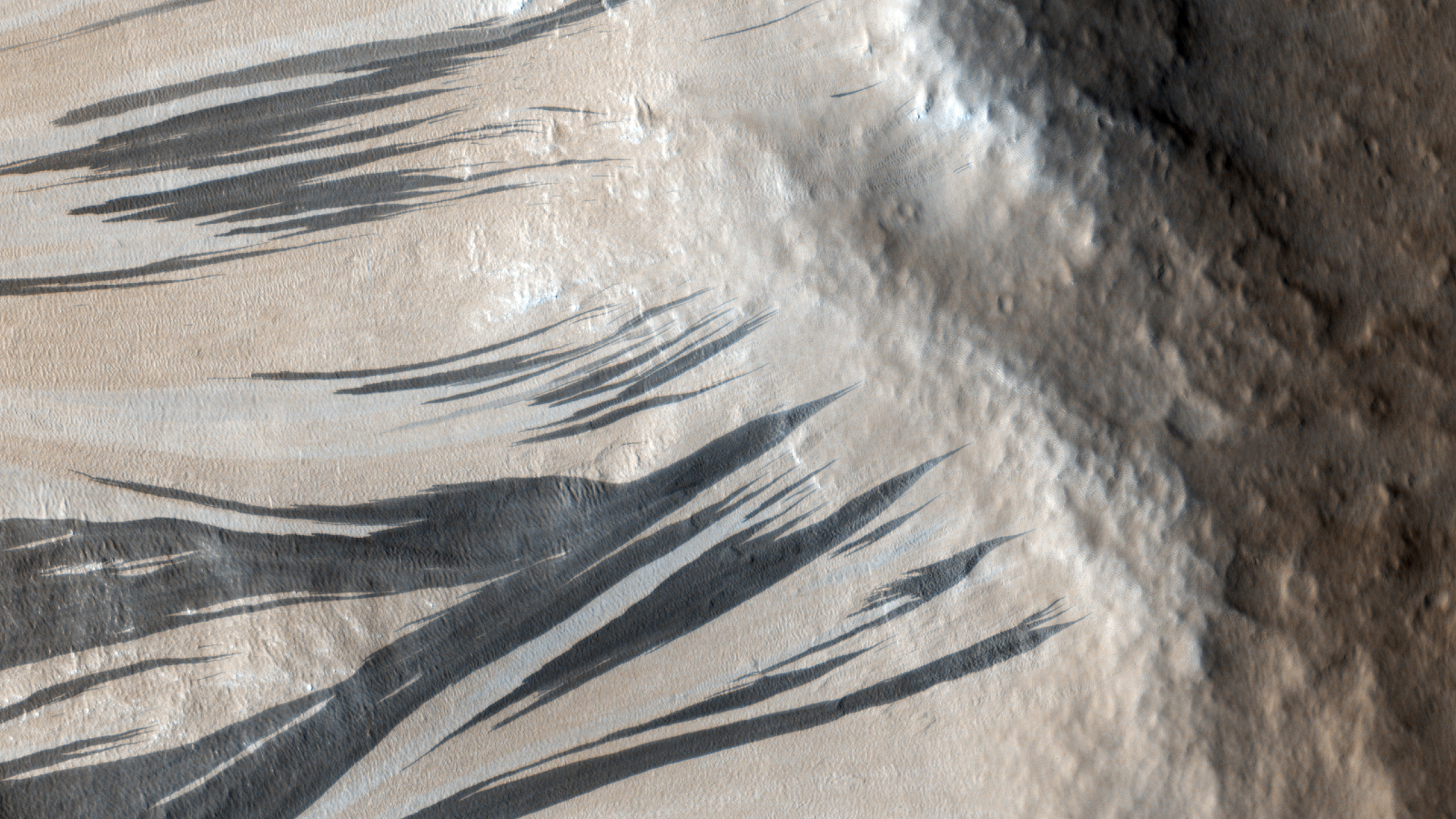

2 million black 'streaks' on Mars finally have an explanation, solving 50-year mystery

2 million black 'streaks' on Mars finally have an explanation, solving 50-year mystery

The Green River flows through the Canyon of Lodore, where it has eroded a ravine with 2,300-foot (700 m) walls. Two competing theories have previously tried to explain why the river ran this course, but neither is particularly convincing, Smith said.

One hypothesis is that the Yampa River to the south of the Uinta Mountains cut northward through the formation and created a channel for the Green River. This would have required a tremendous amount of force, which the Yampa River is unlikely to have produced, because it isn't particularly big. "If this were credible, then you would expect giant canyons running through all mountain ranges, but that's not the case," Smith said.

The other theory is that sediments accumulated and temporarily elevated the Green River so that it overtopped the Uintas and carved its path through them, but the available evidence doesn't support this either. "The sediments that you find here aren't as high as the Canyon of Lodore," Smith said.

Instead, the researchers behind the new study suggest the Uinta Mountains subsided to the point where the Green River could flow over them. The researchers propose that a phenomenon called a "lithospheric drip" tugged the mountains down before a rebound effect caused the landscape to rise upwards once more, resulting in the topography we see today.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.The findings were published Monday (Feb. 2) in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface.

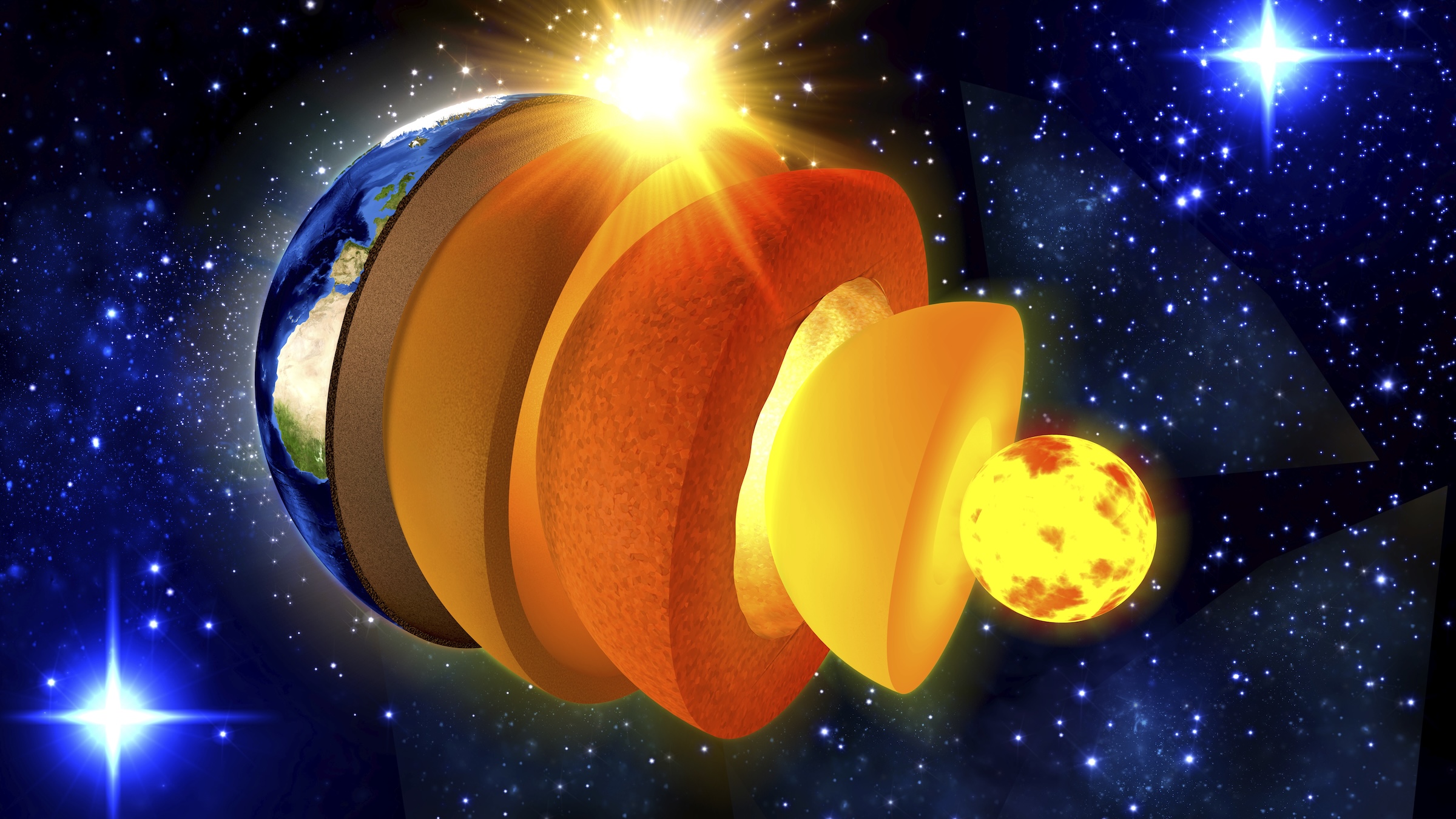

Lithospheric drips are high-density regions that can form directly beneath mountains, where Earth's crust meets the top of the mantle — the layer of the planet between the crust and the outer core. The weight of the mountains increases the pressure at the base of the crust, forming minerals like garnet that are heavier than mantle rocks. Eventually, these minerals form a blob that drips from the base of the crust, dragging the mountains down and reducing their elevation at Earth's surface.

Lithospheric drips trigger a rebound effect when they finally detach and sink into the mantle. The concept of these drips is relatively recent, but evidence of them has been found in several places, including the Andes. "They can happen wherever you have had a mountain range form, and they can happen at any time," Smith said.

You may like-

What's the oldest river in the world?

What's the oldest river in the world?

-

Giant structure discovered deep beneath Bermuda is unlike anything else on Earth

Giant structure discovered deep beneath Bermuda is unlike anything else on Earth

-

2 million black 'streaks' on Mars finally have an explanation, solving 50-year mystery

2 million black 'streaks' on Mars finally have an explanation, solving 50-year mystery

A telltale sign of lithospheric dripping is a bullseye-like pattern of uplift on Earth's surface. Smith and his colleagues modeled geological processes in the Uinta Mountains based on the unusual profiles of rivers there and found such a pattern.

The researchers also analyzed seismic tomography images — 3D maps of Earth's interior that are created using seismic waves — from a previous study. They found a blob 120 miles (200 kilometers) deep in the mantle beneath the Uintas that looked very much like an old lithospheric drip, providing strong evidence for this mechanism, Smith said.

Next, the researchers used the observed drip's depth and size to calculate when it detached from the bottom of the Uinta Mountains. They found that it likely broke free between 2 million and 5 million years ago, which fitted with the model's predictions of when the mountains rebounded and matches estimates of when the Green River first cut through the mountains.

The drip lowered the mountains so much that they became "the path of least resistance," Smith said. Once the Green River started flowing over the Uintas, it kept incising the mountains, creating structures like the Canyon of Lodore, he added.

RELATED STORIES—The geology that holds up the Himalayas is not what we thought, scientists discover

—North America is 'dripping' down into Earth's mantle, scientists discover

—Mount Everest is taller than it should be — and a weird river may be to blame

Other experts who weren't involved in the research suggested this explanation could ultimately solve the longstanding mystery.

Mitchell McMillan, a research geologist at the Georgia Institute of Technology, said that lithospheric dripping is a plausible explanation for why the Green River flows the way that it does.

"The most exciting aspect of this study is that it uses clues on Earth's surface to understand mantle processes and how they might affect mountain belts," McMillan told Live Science in an email. "Whether or not the drip hypothesis ultimately ends up being correct here, this study is a valuable demonstration of such an approach."

Article SourcesSmith, A., Fox, M., Miller, S., Morriss, M. & Anderson, L. (2026). A lithospheric drip triggered Green and Colorado River integration. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface. https://doi.org/10.1029/2025JF008733

TOPICS mountains Sascha PareSocial Links NavigationStaff writer

Sascha PareSocial Links NavigationStaff writer Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

View MoreYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more What's the oldest river in the world?

What's the oldest river in the world?

Giant structure discovered deep beneath Bermuda is unlike anything else on Earth

Giant structure discovered deep beneath Bermuda is unlike anything else on Earth

2 million black 'streaks' on Mars finally have an explanation, solving 50-year mystery

2 million black 'streaks' on Mars finally have an explanation, solving 50-year mystery

18 of Earth's biggest river deltas — including the Nile and Amazon — are sinking faster than global sea levels are rising

18 of Earth's biggest river deltas — including the Nile and Amazon — are sinking faster than global sea levels are rising

Enormous freshwater reservoir discovered off the East Coast may be 20,000 years old and big enough to supply NYC for 800 years

Enormous freshwater reservoir discovered off the East Coast may be 20,000 years old and big enough to supply NYC for 800 years

Eruptions of ocean volcanoes may be the echoes of ancient continental breakups

Latest in Geology

Eruptions of ocean volcanoes may be the echoes of ancient continental breakups

Latest in Geology

Chocolate Hills: The color-changing mounds in the Philippines that inspired legends of mud-slinging giants

Chocolate Hills: The color-changing mounds in the Philippines that inspired legends of mud-slinging giants

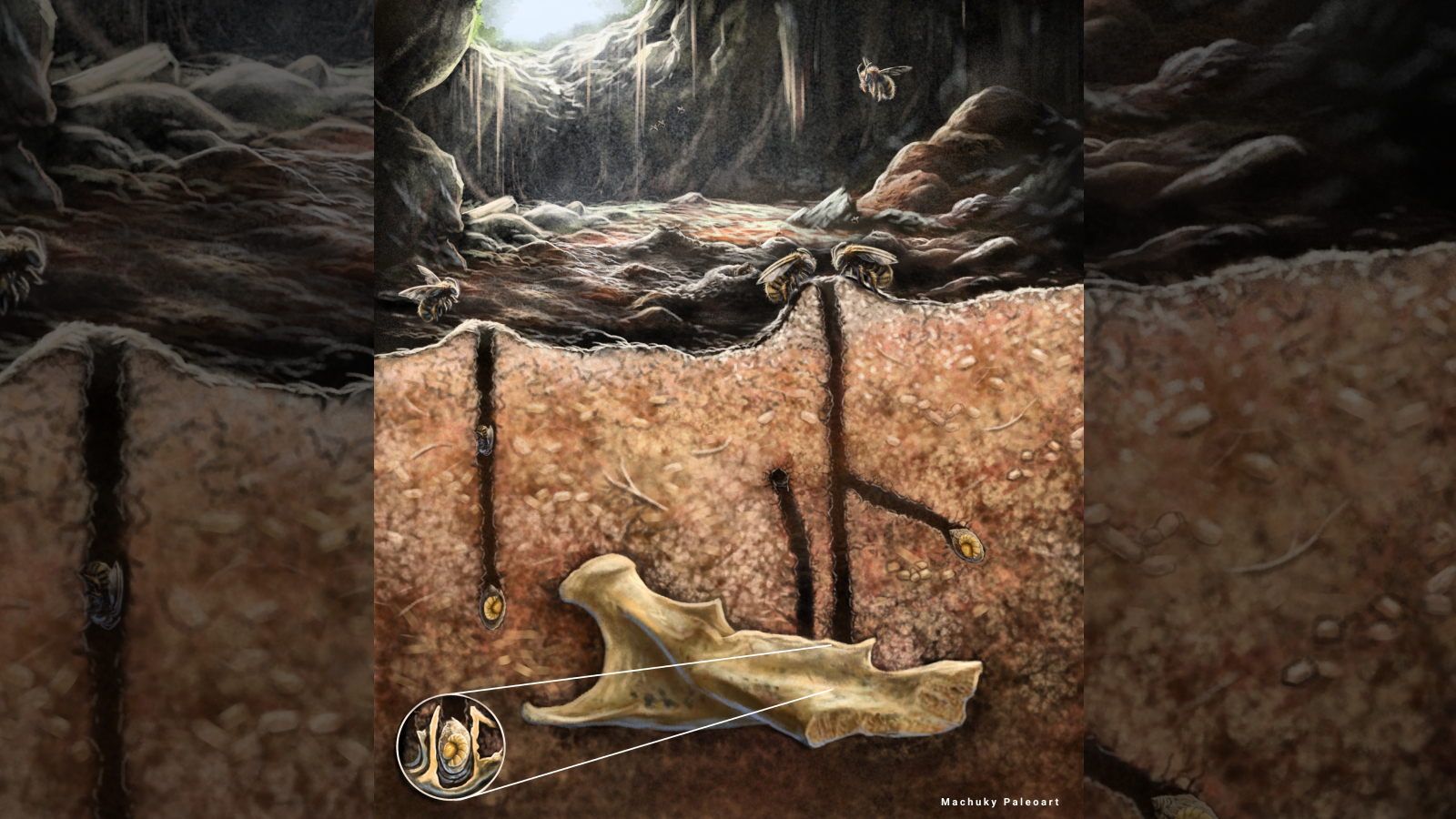

Ancient burrowing bees made their nests in the tooth cavities and vertebrae of dead rodents, scientists discover

Ancient burrowing bees made their nests in the tooth cavities and vertebrae of dead rodents, scientists discover

Giant structure discovered deep beneath Bermuda is unlike anything else on Earth

Giant structure discovered deep beneath Bermuda is unlike anything else on Earth

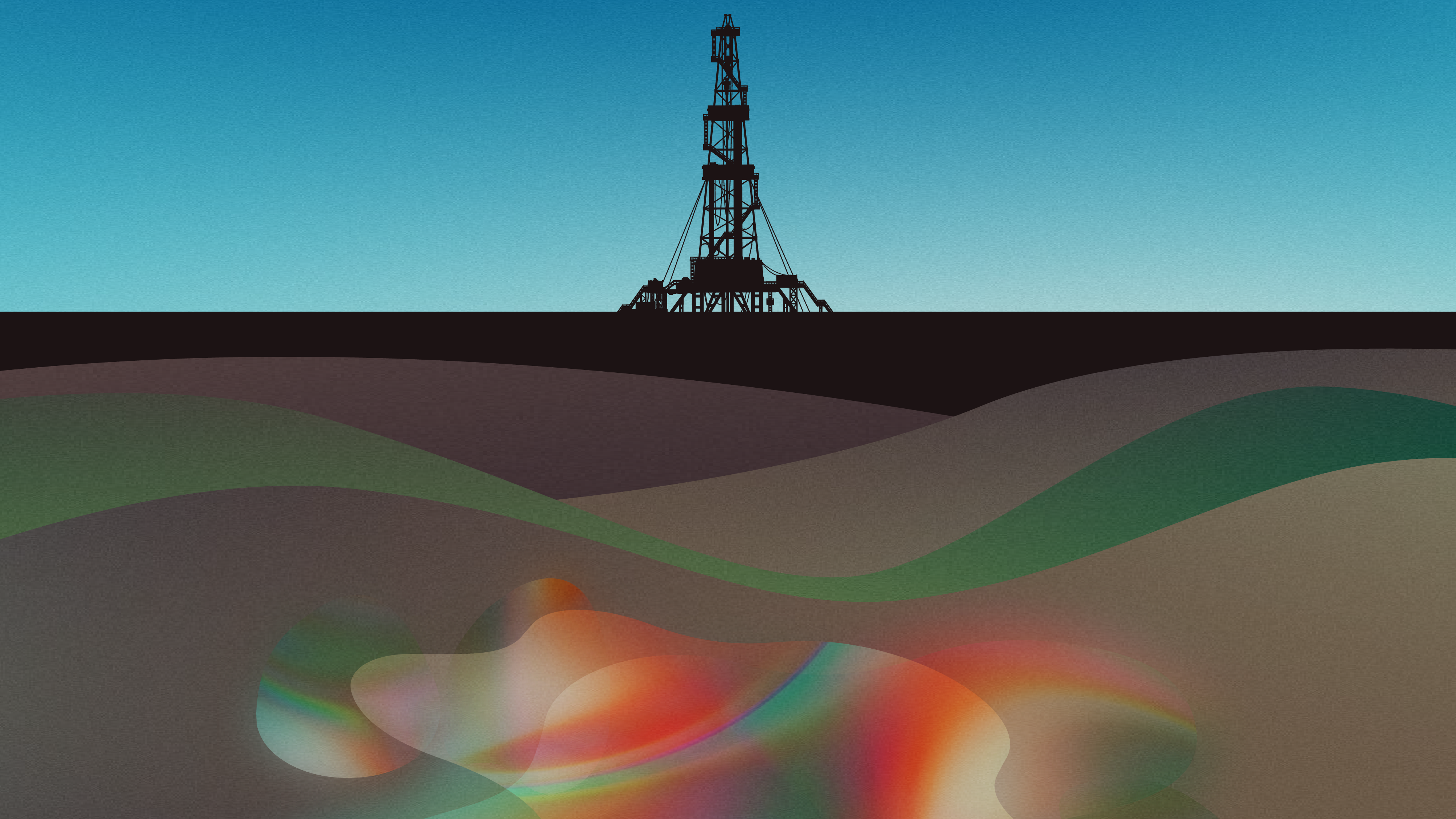

Earth's crust hides enough 'gold' hydrogen to power the world for tens of thousands of years, emerging research suggests

Earth's crust hides enough 'gold' hydrogen to power the world for tens of thousands of years, emerging research suggests

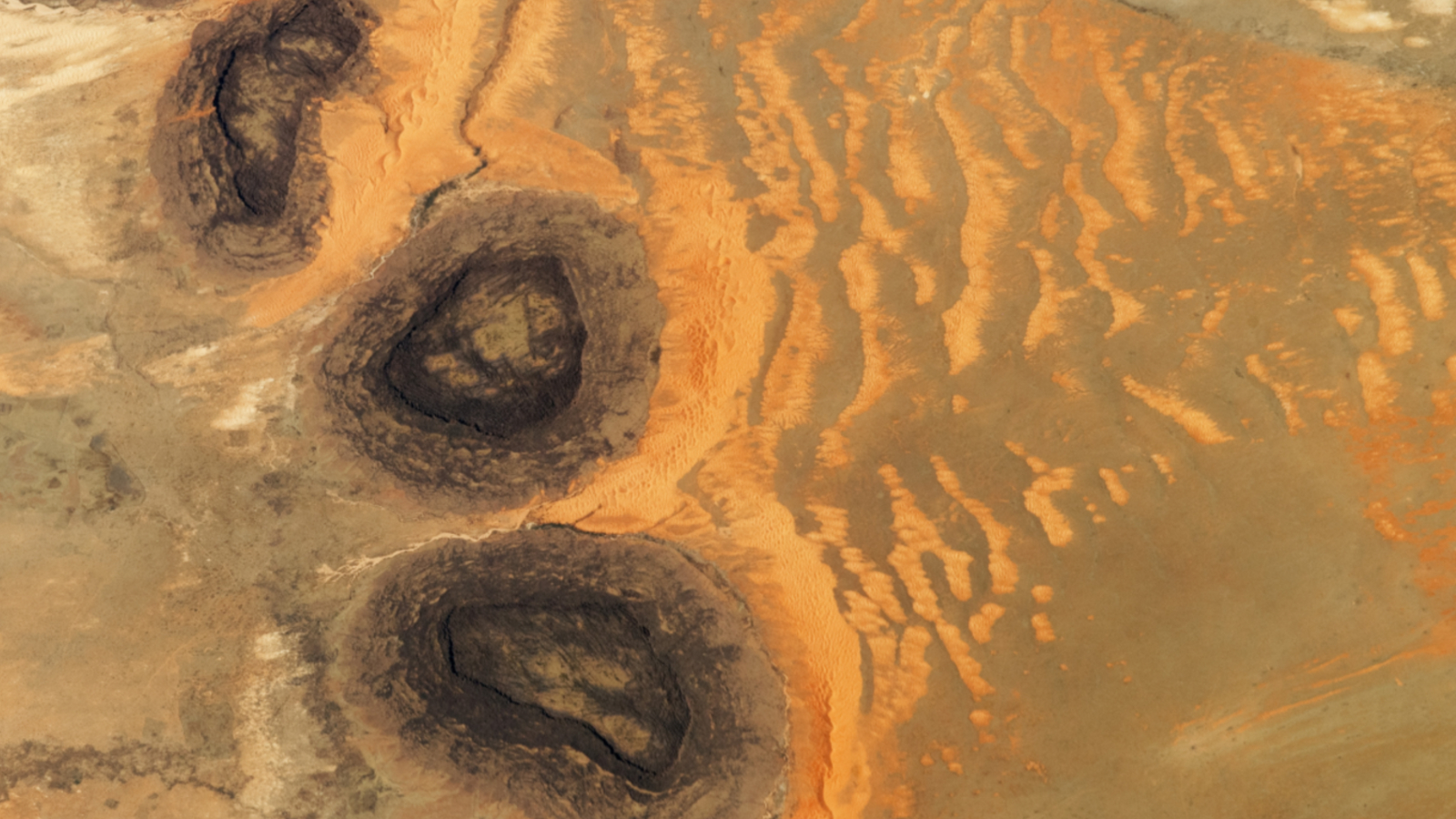

Trio of 'black mesas' leftover from Paleozoic era spawn rare sand dunes in the Sahara

Trio of 'black mesas' leftover from Paleozoic era spawn rare sand dunes in the Sahara

Sistema Ox Bel Ha: A vast hidden system that's the longest underwater cave in the world

Latest in News

Sistema Ox Bel Ha: A vast hidden system that's the longest underwater cave in the world

Latest in News

Artemis II simulated launch window opens tonight as NASA delays mission due to 'rare Arctic outbreak'

Artemis II simulated launch window opens tonight as NASA delays mission due to 'rare Arctic outbreak'

Earth is 'missing' lighter elements. They may be hiding in its solid inner core.

Earth is 'missing' lighter elements. They may be hiding in its solid inner core.

Lifespan may be 50% heritable, study suggests

Lifespan may be 50% heritable, study suggests

Astronomers spot 'time-warped' supernovas whose light both has and hasn't reached Earth

Astronomers spot 'time-warped' supernovas whose light both has and hasn't reached Earth

Life may have rebounded 'ridiculously fast' after the dinosaur-killing asteroid impact

Life may have rebounded 'ridiculously fast' after the dinosaur-killing asteroid impact

'Nose-in-a-dish' reveals why the common cold hits some people hard, while others recover easily

LATEST ARTICLES

'Nose-in-a-dish' reveals why the common cold hits some people hard, while others recover easily

LATEST ARTICLES 1Artemis II simulated launch window opens tonight as NASA delays mission due to 'rare Arctic outbreak'

1Artemis II simulated launch window opens tonight as NASA delays mission due to 'rare Arctic outbreak'- 2Jiawen Galaxy Projector Light review

- 3What to buy as a beginner runner: Must-haves vs non-essentials

- 4Ribchester Helmet: A rare 'face mask' helmet worn by a Roman cavalry officer 1,900 years ago

- 5'It's similar to how Google can map your home without your consent': Why using aerial lasers to map an archaeology site should have Indigenous partnership