- Archaeology

A study of dog bones across several Iron Age sites in Bulgaria has shown that people ate dog meat.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

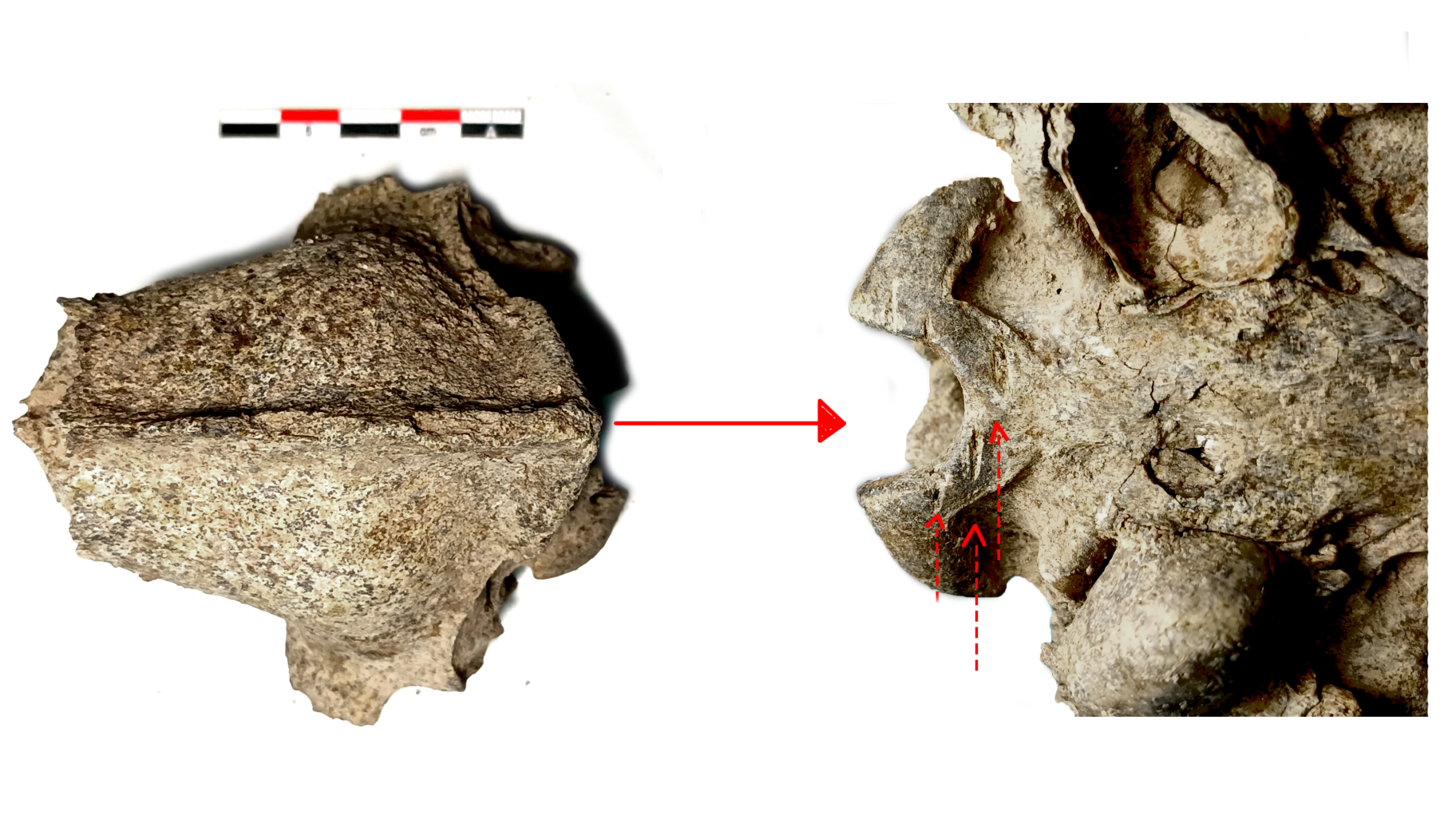

An Iron Age dog burial from Chirpan, Bulgaria

(Image credit: Stella Nikolova)

Share

Share by:

An Iron Age dog burial from Chirpan, Bulgaria

(Image credit: Stella Nikolova)

Share

Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Cut marks on dozens of canine skeletons found at archaeological sites in Bulgaria suggest that people were eating dog meat 2,500 years ago — and not just because they had no other options.

"Dog meat was not a necessity eaten out of poverty, as these sites are rich in livestock, which was the main source of protein," Stella Nikolova, a zooarchaeologist at the National Archaeological Institute with Museum of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences and author of a study published in December in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, told Live Science. "Evidence shows that dog meat was associated with some tradition involving communal feasting."

Although consuming dog meat — a practice sometimes called cynophagy — is considered taboo in contemporary European societies, this hasn't always been the case. Historical accounts mention that the ancient Greeks sometimes ate dog meat, and archaeological analysis of dog skeletons from Greece has confirmed those stories.

You may like-

5,000-year-old dog skeleton and dagger buried together in Swedish bog hint at mysterious Stone Age ritual

5,000-year-old dog skeleton and dagger buried together in Swedish bog hint at mysterious Stone Age ritual

-

Neanderthals cannibalized 'outsider' women and children 45,000 years ago at cave in Belgium

Neanderthals cannibalized 'outsider' women and children 45,000 years ago at cave in Belgium

-

People in China lived alongside 'chicken-killing tigers' long before domestic cats arrived

People in China lived alongside 'chicken-killing tigers' long before domestic cats arrived

During the Iron Age (fifth to first centuries B.C.), a cultural group known as the Thracians lived to the northeast of the Greeks, in what is now Bulgaria. The Greeks and Romans considered the Thracians to be uncivilized and warlike, and in the middle of the first century A.D., Thrace became a province of the Roman Empire. Like the Greeks, the Thracians were said to have consumed dog meat.

To look into the question of whether the Thracians ate dogs, Nikolova examined skeletons and previously published data from 10 Iron Age archaeological sites spread throughout Bulgaria. She discovered that most of the dogs had medium-sized snouts and medium-to-large withers heights, making them roughly the size of modern German shepherds.

But the large number of butchery marks on many of the bones revealed the dogs were not man's best friend. "It is most probable they were kept as guard dogs, as the sites have a lot of livestock," Nikolova said. "I don't believe they were viewed as pets in the modern sense."

At the site of Emporion Pistiros, an Iron Age trade center in inland Thrace, archaeologists found more than 80,000 animal bones — and dogs made up 2% of the total. When Nikolova looked closely at the dog bones from Pistiros, she found that nearly 20% of them had butchery marks made by metal tools. Two lower dog jaws also had burned teeth, possibly the result of someone removing hair and fur with fire prior to butchering and cooking the animals.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter nowContact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.

"The highest number of cuts and fragmentation is observed in the parts with the densest muscle tissue — the upper quarter of the hind limbs," Nikolova said. "There are also cuts on ribs, although in dogs they would yield little meat." The cuts Nikolova noticed on the dogs followed roughly the same pattern as those on sheep and cattle at the site, suggesting all of the animals were being butchered in a similar manner.

Because the Thracians had many other animals more traditionally associated with meat consumption, such as pigs, birds, fish and wild mammals, Nikolova does not think the Thracians were eating dogs as a last resort.

At Pistiros, butchered dog bones were discovered within the discarded remains of feasts and in general domestic trash heaps, Nikolova said, meaning dog flesh may have been consumed in different ways. "So, while linked to a certain tradition, it was not confined to that title and was an occasional 'delicacy,'" she said.

RELATED STORIES—Jamestown colonists killed and ate the dogs of Indigenous Americans

—5,000-year-old dog skeleton and dagger buried together in Swedish bog hint at mysterious Stone Age ritual

—Pet dog buried 6,000 years ago is earliest evidence of its domestication in Arabia

Several other Bulgarian archaeological sites Nikolova investigated had evidence of cut and burned dog bones, as did sites in Greece and Romania, meaning "we cannot label dog meat consumption as unique to Ancient Thrace, but a somewhat regular practice that was carried out in the 1st millennium BC in the North-East Mediterranean," Nikolova wrote in her study.

Nikolova plans to further investigate the role of dogs at Pistiros as part of the Corpus Animalium Thracicorum project. She noted that the butchered dogs at Pistiros are from the first part of the Iron Age, but later on the people there began burying intact dogs, so she hopes to determine whether there was a change in people's attitude over time that made dogs a less acceptable source of food.

Article SourcesNikolova, S. (2025). Dog meat in late Iron Age Bulgaria: necessity, delicacy, or part of a wider intercultural tradition? International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.70062

Animal quiz: Test yourself on these fun animal trivia questions

Kristina KillgroveSocial Links NavigationStaff writer

Kristina KillgroveSocial Links NavigationStaff writerKristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Show More CommentsYou must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Neanderthals cannibalized 'outsider' women and children 45,000 years ago at cave in Belgium

Neanderthals cannibalized 'outsider' women and children 45,000 years ago at cave in Belgium

People in China lived alongside 'chicken-killing tigers' long before domestic cats arrived

People in China lived alongside 'chicken-killing tigers' long before domestic cats arrived

Large, bone-crushing dogs stalked 'Rhino Pompeii' after Yellowstone eruption 12 million years ago, ancient footprints reveal

Large, bone-crushing dogs stalked 'Rhino Pompeii' after Yellowstone eruption 12 million years ago, ancient footprints reveal

2,400-year-old 'sacrificial complex' uncovered in Russia is the richest site of its kind ever discovered

2,400-year-old 'sacrificial complex' uncovered in Russia is the richest site of its kind ever discovered

2,000-year-old Celtic teenager may have been sacrificed and considered 'disposable'

2,000-year-old Celtic teenager may have been sacrificed and considered 'disposable'

Brutal lion attack 6,200 years ago severely injured teenager — but somehow he survived, skeleton found in Bulgaria reveals

Latest in Archaeology

Brutal lion attack 6,200 years ago severely injured teenager — but somehow he survived, skeleton found in Bulgaria reveals

Latest in Archaeology

480,000-year-old ax sharpener is the oldest known elephant bone tool ever discovered in Europe

480,000-year-old ax sharpener is the oldest known elephant bone tool ever discovered in Europe

People, not glaciers, transported rocks to Stonehenge, study confirms

People, not glaciers, transported rocks to Stonehenge, study confirms

Some of the oldest harpoons ever found reveal Indigenous people in Brazil were hunting whales 5,000 years ago

Some of the oldest harpoons ever found reveal Indigenous people in Brazil were hunting whales 5,000 years ago

World's oldest rock art, giant reservoir found beneath the East Coast seafloor, black hole revelations, and a record solar radiation storm

World's oldest rock art, giant reservoir found beneath the East Coast seafloor, black hole revelations, and a record solar radiation storm

5,500-year-old human skeleton discovered in Colombia holds the oldest evidence yet that syphilis came from the Americas

5,500-year-old human skeleton discovered in Colombia holds the oldest evidence yet that syphilis came from the Americas

2.6 million-year-old jaw from extinct 'Nutcracker Man' is found where we didn't expect it

Latest in News

2.6 million-year-old jaw from extinct 'Nutcracker Man' is found where we didn't expect it

Latest in News

2,500 years ago, people in Bulgaria ate dog meat at feasts and as a delicacy, archaeological study finds

2,500 years ago, people in Bulgaria ate dog meat at feasts and as a delicacy, archaeological study finds

'Pain sponge' derived from stem cells could soak up pain signals before they reach the brain

'Pain sponge' derived from stem cells could soak up pain signals before they reach the brain

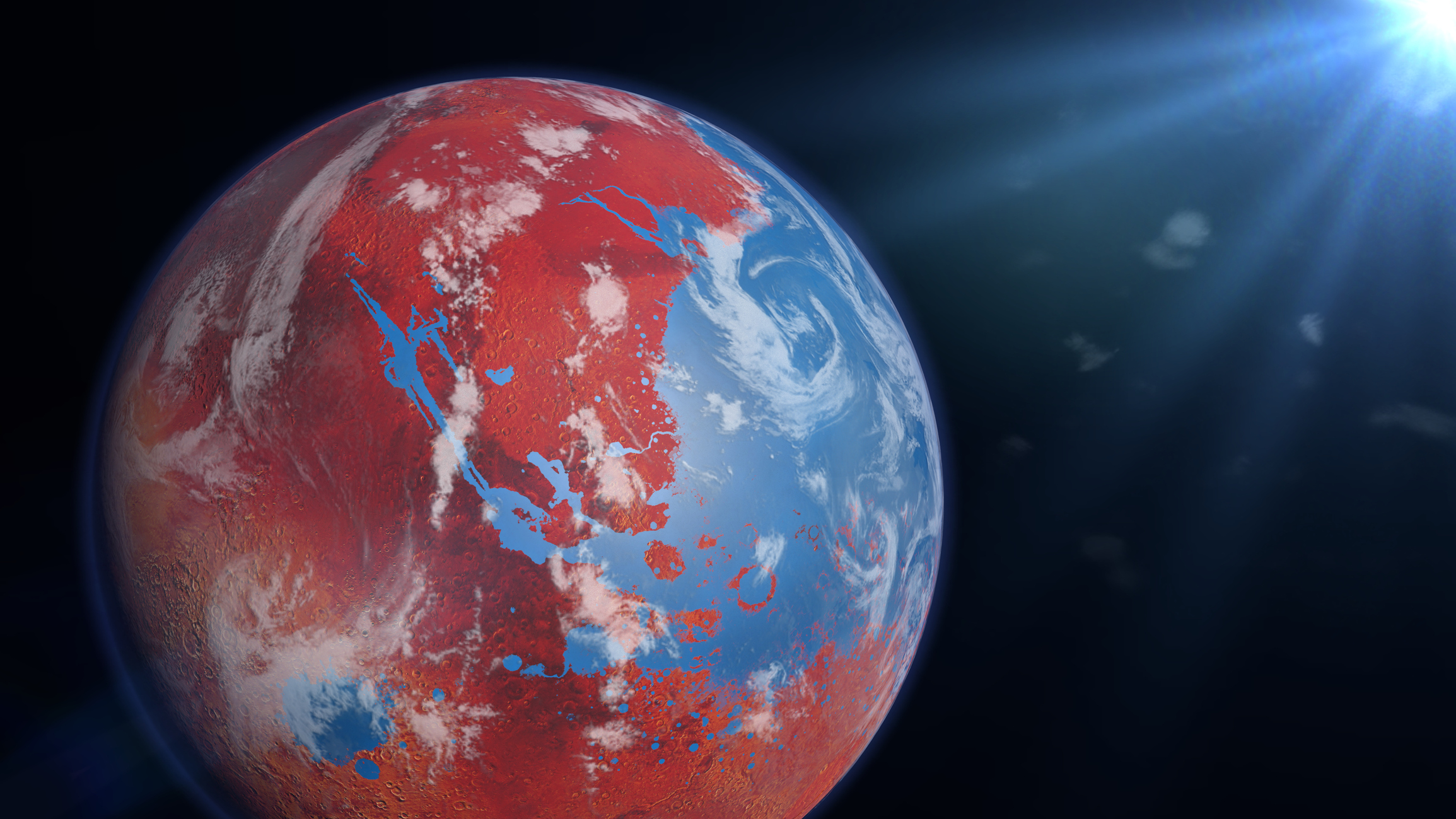

An ocean the size of the Arctic once covered half of Mars, new images hint

An ocean the size of the Arctic once covered half of Mars, new images hint

Arctic blast probably won't cause trees to explode in the cold — but here's what happens if and when they do go boom

Arctic blast probably won't cause trees to explode in the cold — but here's what happens if and when they do go boom

Wegovy now comes in pill form — here's how it works

Wegovy now comes in pill form — here's how it works

AI can develop 'personality' spontaneously with minimal prompting, research shows. What does that mean for how we use it?

LATEST ARTICLES

AI can develop 'personality' spontaneously with minimal prompting, research shows. What does that mean for how we use it?

LATEST ARTICLES 1480,000-year-old ax sharpener is the oldest known elephant bone tool ever discovered in Europe

1480,000-year-old ax sharpener is the oldest known elephant bone tool ever discovered in Europe- 2AI can develop 'personality' spontaneously with minimal prompting, research shows. What does that mean for how we use it?

- 3Science news this week: The world's oldest rock art, giant freshwater reservoir found off the East Coast, and the biggest solar radiation storm in decades

- 4Why the rise of humanoid robots could make us less comfortable with each other

- 5Why don't you usually see your nose?